Seven or eight years ago I met Harvey Dinnerstein for lunch, in a restaurant near the Art Students League of New York. There are three topics I remember from that lunch, the range of which accurately represents the amount of ground we often covered. The first was the subject of other artists, a kind of continuous discussion we’d resume naturally, sometimes after years of hiatus, and about which we rarely agreed. I mentioned a couple of major figurative painters from the late twentieth century I held in high esteem, whom Harvey dismissed out-of-hand. These dependable disagreements in no way diminished the enjoyment of our talks. Segueing to the present day, Harvey asked me if it was possible to earn a living selling one’s artwork online. Though he didn’t own a computer or surf the internet, he retained a curiosity about the technology and its potential usefulness. Perhaps he was exploring alternatives; at around the same time, Harvey inquired about living in rural Connecticut. Given his age, it seemed an unrealistic proposition. Also, Harvey was a bona fide New Yorker. One could scarcely have imagined him moving to Old Lyme.

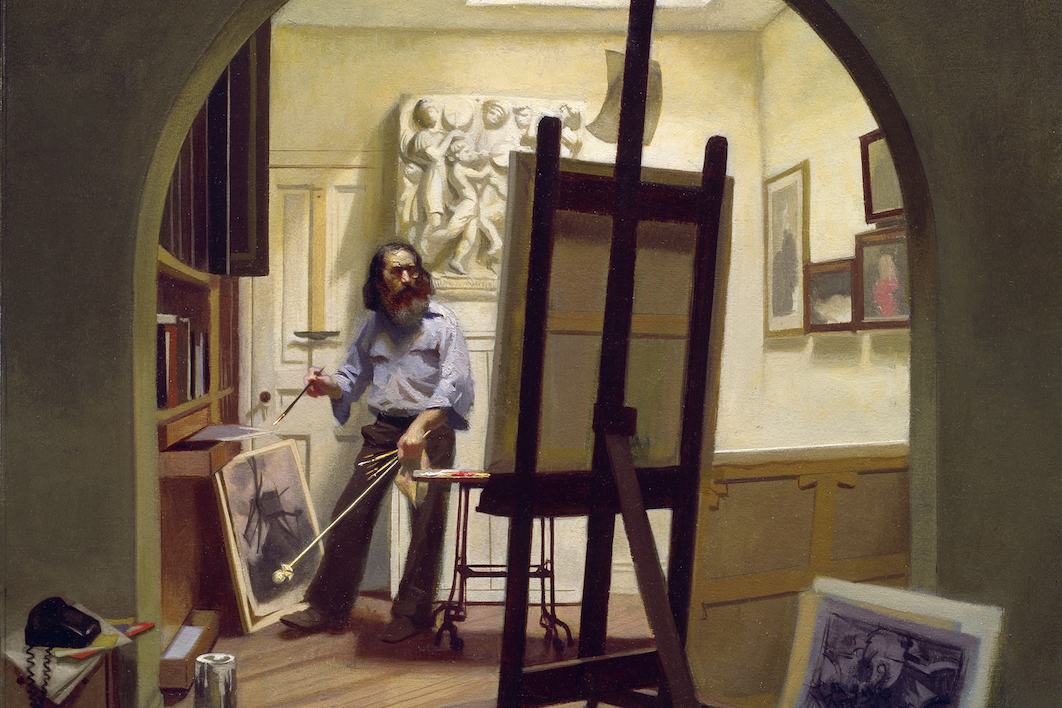

The third topic I remember was the hypothetical disposition of his estate. Harvey puzzled over which of his family members upon whom to bestow the responsibility of managing his life’s work. Eventually, an alternative presented itself in the form of the League. Harvey Dinnerstein: Reflections on Life and Work at the Phyllis Harriman Mason Gallery is a selection of art and archival material gifted to the school by the Dinnerstein Estate. League President Robin Lechter Frank and instructor Sam Goodsell did the heavy lifting of cataloguing the work, and gallery director Ksenia Nouril faced the formidable task of choosing a few dozen pieces from the thousand that his estate left to the League. The curatorial choices reflect well on both the artist and the institution where Harvey taught for forty years.

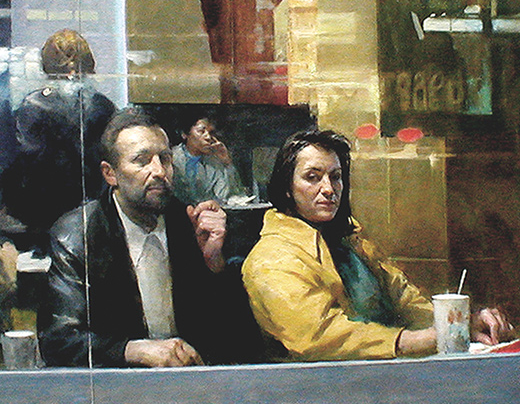

Reflections does an admirable job touching the bases of his career: here’s the artist as journalist; portraitist; self-portraitist; intimist; chronicler of pregnancy, childhood and old age; observer of the city’s parks and subways; rhetorician; social commentator; allegorist; painter of still life; illustrator. When I registered for his class at the National Academy of Design in 1980, I was impressed by Parade, a multi-figure mural that taps into the zeitgeist of the sixties. But it was really the liveliness of his draftsmanship on a smaller scale that hooked me. The current show includes a drawing of a Muslim woman and child on the subway, scrawled on the back of a manila envelope, a pastel of a wailing newborn, and a charcoal study of a confrontational Mr. Meltzer, standing with his hands on his hips. Harvey could draw. I cannot think of another contemporary artist who draws with such visceral assurance, nor who is able to turn on a dime and weave sensitive illustrations in pen and ink, as Harvey did for a reissue of At the Back of the North Wind. One of the qualities that set Harvey’s work apart from several generations of traditional realists was the technical acumen that enabled his eclecticism.

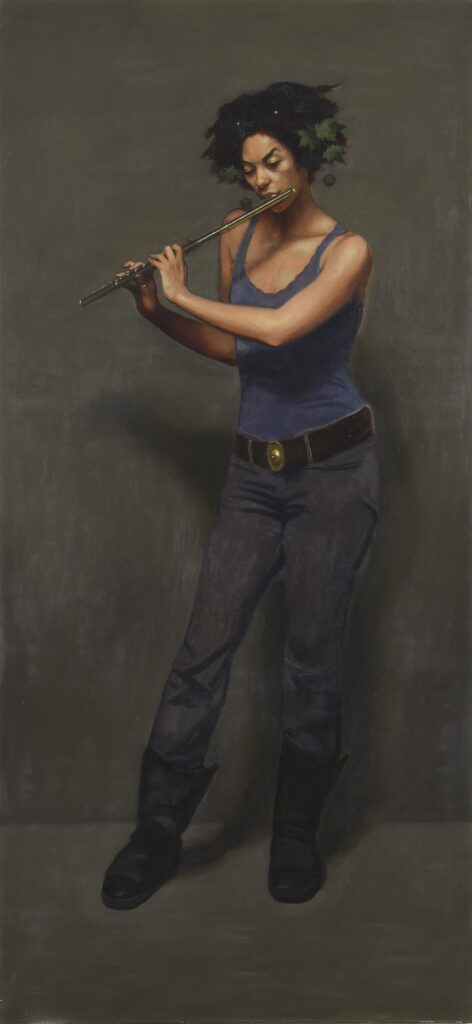

Another quality, as I’ve already implied, was his engagement, both emotionally and intellectually, with the human condition. It was the motivation for Harvey’s trip with Burt Silverman to Montgomery, Alabama, in 1956 to cover the Civil Rights movement in its early years. It’s there in the extensive series of life-size standing portraits that he painted of friends, family and models, as in Bamboo Flute (Ralph McAden), and a study of the erstwhile League model Pigeon playing a flute, the two canvases bookending the gallery’s back wall. In 2019, I ran into Harvey at the press opening of the Frick’s Moroni exhibition. He admired the imposing standing figure, Gian Ludovico Madruzzo, and it occurred to me that Moroni’s finely cut patterns and intense observation aligned with what Harvey had done. In one important way, the big portraits showed Harvey tacking closer to and perhaps shadowboxing with paintings like Eakins’s Thinker, since most of the subjects were of his choosing, rather than commissions. They are intentional statements on behalf of the individual, conceived in a time of creeping dehumanization. Who else had the chops to take on such a project, to paint over a dozen life-size portraits of otherwise unknown people? In the wake of several recent exhibitions of Barkley Hendricks’s portraits, I’ve thought about the need to reassess Harvey’s paintings for their contribution to a modern iconography of New Yorkers of all races, ethnicities and genders. They have not yet received their due.

Harvey’s fondness for the monumental image wasn’t confined to single portraits. His epic ambitions found fuller expression in multi-figure narratives, sometimes depicting urban life in its less savory aspects (the subway and homelessness), sometimes elegiac or elysian (the seasons in Prospect Park). Parade (not in show), perhaps his best known work, is a counterculture fantasy. The centerpiece of Reflections is Past and Present, an even larger canvas than Parade—at over eight by fourteen feet, it’s by far his largest work. Filling the picture plane is the facade of Harvey’s longtime home on President Street in Brooklyn. His wife appears at a window, his mother sits on the front steps. At far right, the artist himself is seated in profile, painting at a French easel. As much as it is an autobiographical summation, Past and Present underscores the role of lyricism in Harvey’s art: family is all but upstaged by street musicians. In front of Harvey, a woman walks barefoot down the street, a tambourine raised above her head.

It was a visit to the Louvre, and the example of Gericault’s Raft of the Medusa that appears to have inspired the major narratives:

But if you step back, and look at the whole bloody thing, it works on a certain level that just knocked me out. And the fact that Géricault took a contemporary incident and transformed it on some mythic level was astonishing. You can look at the painting, and not even know about the raft of the Medusa or the politics of the moment, but it reaches that other epic level. That’s what I aspire to.

Harvey’s use of the word “mythic” is important, because hundreds of his students—myself included—and probably many more casual viewers, were apt to think of him as an academic artist continuing a realist tradition. At our last in-person meeting in a lower Manhattan hospital, we discussed two current exhibitions at the Met, one the drawings of Jacques-Louis David, the other the paintings of Winslow Homer. Harvey thought for a bit, then conceded that if he had to choose between the two, he’d take Homer.

This was, to me, the basic contradiction—or reconciliation—of Harvey’s art. His compositions derive from classical sources, while his themes are ultimately romantic. There is the Prospect Park series, the elegant arched bridges seen in all seasons, foreboding or sheltering, sometimes a setting for lovers and musicians, a modern Arcadia. But the classic/romantic dichotomy is far from the only incongruity, and I suspect Harvey enjoyed painting with both hands, so to speak. In the introduction to his solo exhibition at the Butler Institute of American Art in 1994, he wrote about the tension between naturalism and classicism:

Though these qualities may seem contradictory, I believe they compliment and reinforce each other. There is a naturalistic view, simply concerned with surface appearance and transitory effects of nature that I find unfulfilling, and equally troublesome to me are arid qualities of classical form that lack the vigor of life. It is the difficult subtle balance, or tension, between these two elements that I hope to arrive at.

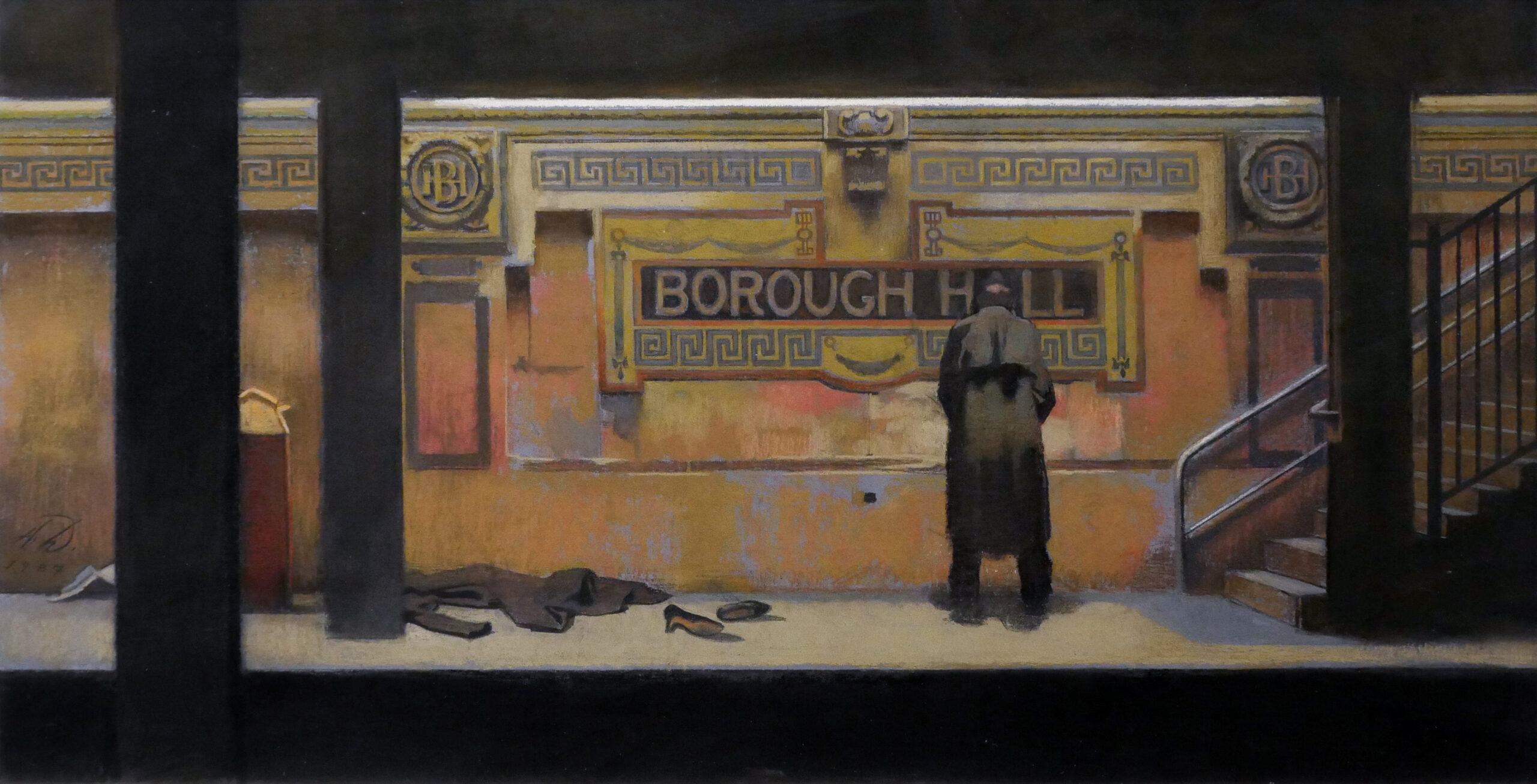

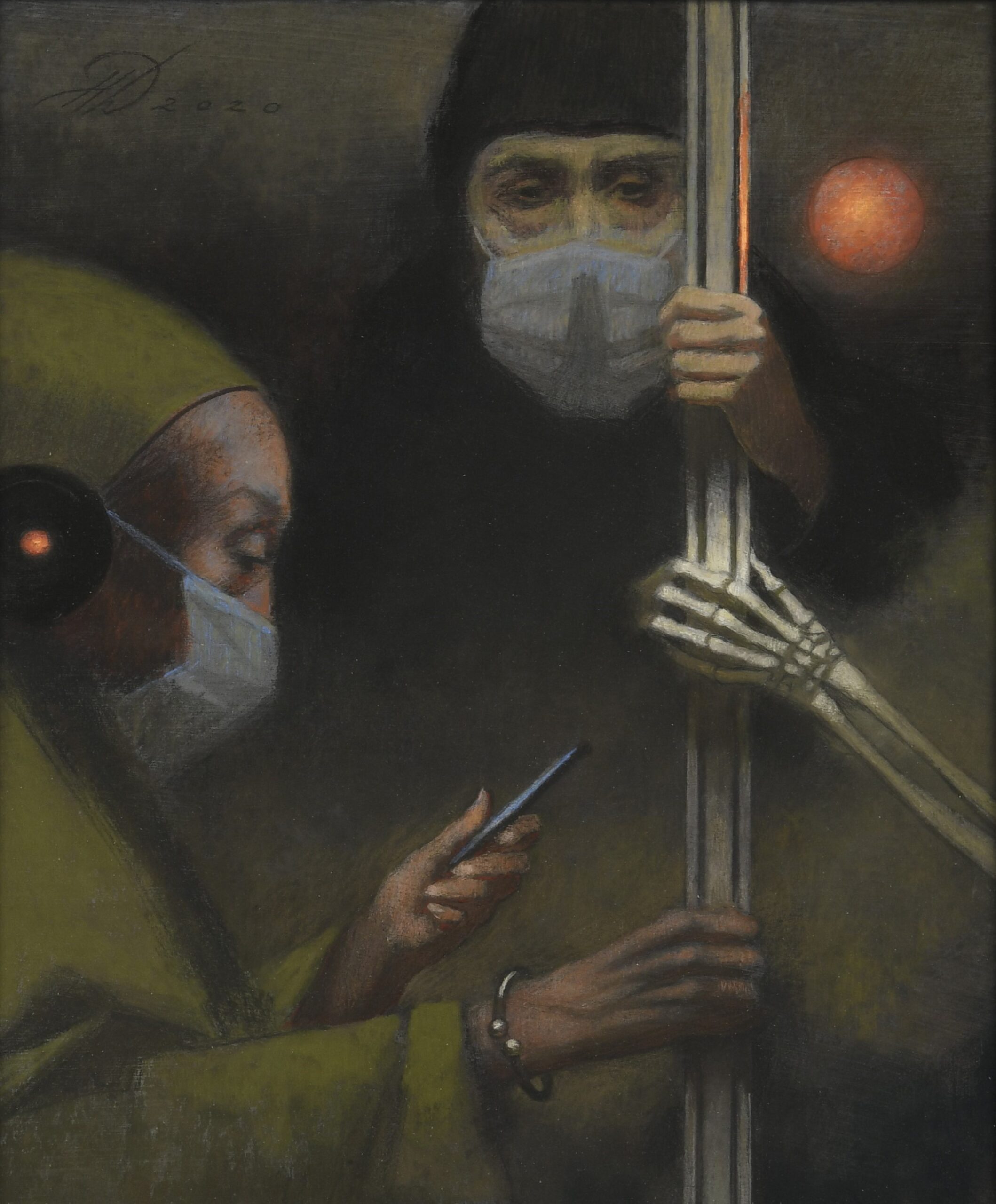

Harvey responded to 9/11 and the pandemic with dark images. The symbolism wasn’t subtle. A skeletal hand grips a subway pole in Death Rides with Subway Passengers from 2020. In a painting of the Guggenheim Museum—one of Harvey’s least favorite sites—the Grim Reaper looms atop the building’s roof, holding a scythe. A pastel, Underground, Sunday Morning, depicts the platform of the Borough Hall subway station, replete with the architectural elements, elaborate masonry and wall designs that Harvey loved to paint. The colors are more pleasant than those of any station I’ve been in of late. It’s all a framework for something unsettling: a winter coat lies abandoned on the platform, alongside a pair of black high heels. Nearby, a lone figure stands with his back to us, urinating on the wall. Harvey had an elegant aesthetic (the grace with which a pregnant woman cradles her stomach), was a fabulist in the best sense of the word (the pastel study of a nude turning a cartwheel for Parade), and he enjoyed being bluntly provocative (the aforementioned man on a platform).

I wish Harvey had on occasion improvised more freely with oils, as he did with dry media. The blazing color and inspired handling of pastels like West Indian Carnival, Brooklyn, were not part of his oil painting repertoire. Not that he would have minded me saying so—I think he was amused by my critical observations. One day after I’d stopped studying, I ran into Harvey on Fifth Avenue, outside the National Academy. He asked what I was doing in the neighborhood, and I said I’d just come from the Met. His reply: “Did you correct all the paintings?”

He was amused by the human condition in general. Harvey Dinnerstein: Reflections on Life and Work is an excellent introduction to Harvey’s ceaseless fascination with the world around him. What’s on display is a sampling of an invaluable gift, the life’s work of one of the most important New York figurative artists of this era.

Harvey Dinnerstein: Reflections on Life and Work continues through July 13, 2024.