Once upon a time the Frick Collection didn’t do blockbusters as did other museums. The permanent collection, constituting arguably the greatest concentration of master works in the country, was a sufficient display. It was possible to memorize the placement of favorite paintings—heck, the holdings were small enough that it was possible to memorize pretty much everything—and be secure in the knowledge that if you left the city for years they’d be in the same spot when you returned. Not a lot of action for the curatorial staff, one imagines.

For a long time, though, the Frick has stealthily presented itinerant productions. Recent installations haven’t been full-fledged shows so much as promotional blurbs for other museums: a handful of masterpieces arrived from Edinburgh last winter, and, more recently, Puerto Rico’s Flaming June—or “Much ado about Orange”—was installed this summer past.

The Frick’s current installation is Andrea del Sarto: The Renaissance Workshop in Action, a show whose title may raise expectations for a production with more oomph, or at least greater exposition of the workshop process. In fact, the heavy scholarship has been saved for the show’s catalogue, which makes sense, given the Frick’s space limitations. The exhibition, comprised of some fifty small drawings, inhabits two rooms in the museum’s lower level, and a third, the Oval Room, on the ground floor. A few paintings are interspersed for the purpose of illuminating relationships between linear ideation and finished product.

To see the drawings in the flesh after familiarity through published reproductions is to be surprised by their diminutive scale. What remains of del Sarto’s drawings are fragments of paper sheets that were central to the creation of painted masterworks in sixteenth-century Florence. In his heyday, circa 1520, del Sarto ran the most influential workshop in Florence, including among his students Pontormo, Rosso Fiorentino, and Vasari, his first biographer. He was considered the equal of Michelangelo, Leonardo, and Raphael, and Vasari described his work as senza errori—free from errors. The compliment stuck, as did Vasari’s less generous characterization of Andrea’s personality. The criticism that his work was premised too much on naturalism at the expense of innovation is perhaps rooted in the value Vasari placed on ambitiousness, as well as his antipathy for del Sarto’s wife. That is not to trivialize genuine aesthetic differences—the tenderness with which del Sarto wields red chalk at times seems to me to presage Watteau, suggesting a more precious sensibility than was considered suitable for the painting of frescoes and altarpieces.

Del Sarto’s naturalism suffuses the Frick show. Many of the drawings were made from the living model; Studies of Hands, one of the exhibition’s few drawings that cannot be matched to a painting, evidences the artist’s love of drawing for its own sake. Both hands are subtly yet solidly modeled by light. Del Sarto’s preference for red chalk furthers the impression that we’re not merely viewing a study whose purpose was utilitarian, but are sharing the draftsman’s quiet warmth of spirit (so enchanting is Study of the Head of an Old Man in Profile that it’s a genuine shock to learn it was drawn from an antique bust). What comes to mind is Degas’ rapture over a drawing by Ingres he had recently purchased:

That is my ideal of genius, a man who finds a hand so lovely, so wonderful, so difficult to render that he will shut himself in all his life, content to do nothing but indicate fingernails.

But there are other notes here as well, rapid conceptual drawings in which del Sarto puzzled out themes and design, as well as those which lay bare the gift for abstraction upon which his observations were grounded. One of the most beautiful works is Study of a Woman, long thought to represent del Sarto’s wife, Lucrezia. It appears to be related to a fragmentary painting now in Berlin, and is memorable for its sense of movement and variety of handling. The features of the portrait are summarily treated, yet the head is fully modeled in light and shadow; much the same balance between naturalistic description and a broad structural comprehension is achieved throughout the sheet. Changes in pressure applied to the chalk account for textural variations. The beguiling lightness of del Sarto’s touch around the head shifts to a crisper, richer handling of the sleeves and culminates in a schematic impression of Lucrezia’s hand, a premonition of Pontormo’s anxious nature. Drawing these separate areas required more than keen observation of different surfaces: it necessitated transitions in del Sarto’s response to those surfaces, without sacrificing the work’s holism.

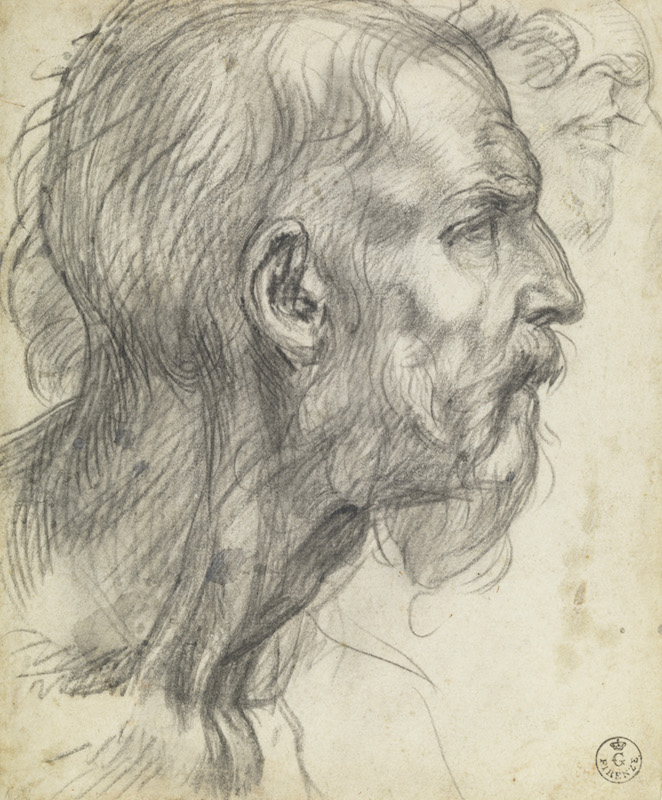

More frenetic in treatment is Study of a Bearded Man in Profile, as overtly energetic a life study as del Sarto produced. Naturalism nearly gives way to the impassioned narrative for which the drawing was a preparation, for this profile shows up as the head of a disciple in del Sarto’s fresco The Last Supper in Florence. The emotive force of the portrait is underscored by rapid gestural strokes of black chalk, economically hatched around the bony structure of the skull, flowingly descriptive of facial hair, forcefully applied in shadow accents and supplemented by a dampened brush—errant splashes of gray wash may be discerned, especially at the neck. Both the centrality and three dimensionality of the ear are remarkable, and imply the primacy of the act of listening.

In the end, the star of the show is a painting, Portrait of a Young Man, for which there are several supposed chalk studies, small drawings that are purely gestural and which represent del Sarto’s initial attempts to nail down pose and composition. The oil is one of the great portraits of the Italian Renaissance, sculpturally wrought yet bathed in atmosphere, an ambiguous presence rendered more mysterious by its lack of identification. Inevitably, this vacuum was temporarily filled by the National Gallery in London, which hung the painting in 1863 as a self-portrait. At the Frick, one may gage both its charms and limitations by walking a few yards to the Living Hall, wherein reside Titian’s Portrait of a Man in a Red Cap and Pietro Aretino, paintings that define the sensual breadth of the Venetian school. It is not del Sarto’s naturalism that is at issue, but rather his more intimate nature. We may extol the artist’s technical attributes to the extent that Vasari did, and bemoan a lack of ambition, but in so doing overlook the qualities that distinguished del Sarto from his contemporaries, and continue to set him apart to this day. His is the province not of dynamism but sublime melancholy.

At the Frick, this unassuming blockbuster has found its perfect setting in New York. In its scrutiny and celebration of draftsmanship as preparatory to and inseparable from the paintings they presaged, this exhibition is invaluable to artists and students. Scholarship aside, it is also a feast of inspired drawing.