As this summer drew to a close, so did the life of an old friend, David Beynon Pena. I hadn’t spoken to Dave in more than twenty years, until a mutual friend urged me to call him, with the news that he had little time left. We talked for about five minutes, Dave pausing at intervals to catch his breath.

We first met as young art students, when my parents were preparing me to move to New York and we visited the Salmagundi Club, where Dave was already a regular at nineteen. Soon afterwards he befriended me at the League. He was like nobody I’d ever met in my largely protected life. Where I was shy and socially inept, he was gregarious and blessed with a galaxy of friends. In contrast to my studiousness as a painter, Dave was flamboyant. Often we’d break from classes for dinner at a pizza joint that once existed where the Extell tower is now going up next door. He’d buy a slice and cover it with hot sauce, a small bottle of which he carried in one pocket, and maybe, for extra protein, add a bag of peanuts from another pocket. Some nights after class we’d walk across town on 57th Street. One late night when he wasn’t in a good way, he stopped in front of Hammer Gallery, took out a black magic marker—in high school, Dave’s canvas was the subway, which he covered in graffiti as “Zephyr 2000″—and wrote on the gallery’s door in his stylized script, “For a good painting, call Jerry Weiss,” and added my dorm pay phone number. The next year he was monitoring Harvey Dinnerstein’s class, then filled with fifty students on the mezzanine level. If you were his friend he’d wave you in to find a spot, with the understanding that a class ticket was optional. His tenure as monitor didn’t last long.

That winter he invited another League friend and me to come out to Brooklyn. Dave was living rent free as the caretaker of a church, and he needed help disposing of a broken washing machine. He cooked us a dinner of rice or pasta, and we bunked down in his loft at the top of the building for the night. Half-dressed the next morning, the three of us wrestled the appliance out the building’s front door and down the steps in sub-freezing cold, and tossed it gently over the fence onto the sidewalk. In the meanwhile the front door closed and locked behind us. Dave quickly concluded that the best option for reentry was to smash a small glass window next to the door and reach his arm fully in to turn the doorknob. As he did so, a police cruiser passed by slowly, two cops watching us in the act of breaking and entering. It says everything of our respective student years to note that this was a memorably entertaining moment for me, but surely nothing more than a blip on Dave’s radar. Dave was unconscionably pretty, which got him into a world of trouble and got him out of it just as often. Years later we were walking near Union Square on a Sunday and I observed the unfairness with which physical grace is bestowed. “Together we look like a movie actor and his Jewish agent.” Dave was 6′ 4″, thin but big-boned and smartly tailored even when his clothing was paint-spattered and he didn’t have a nickel. He was the first person I ever saw wear a dress jacket with short pants, which I thought was a regrettable faux pas, and it would have been for me, but he was right when it came to fashion. He played tennis very well—despite a misshapen ankle, the result of it having been run over by a car when he was a kid—and thought so highly of himself that at sixteen his coach matched him against John McEnroe as a lesson in humility.

His twenties alone comprised a lifetime of adventure. I was privy to schemes, some motivated by financial need, some by the thrill of a shortcut. These would have been spectacularly illegal if acted upon, and would have put me in the position of unwilling accomplice before the act. He must have known in advance I’d strenuously disapprove, but he sought my counsel anyway. I do think that besides our shared interest in painting, this was the basis of our friendship: he saw me as a sober and sensible male presence, which wasn’t actually true, and I saw him as a volatile and romantic character. It was a mismatch maintained by mutual good intentions.

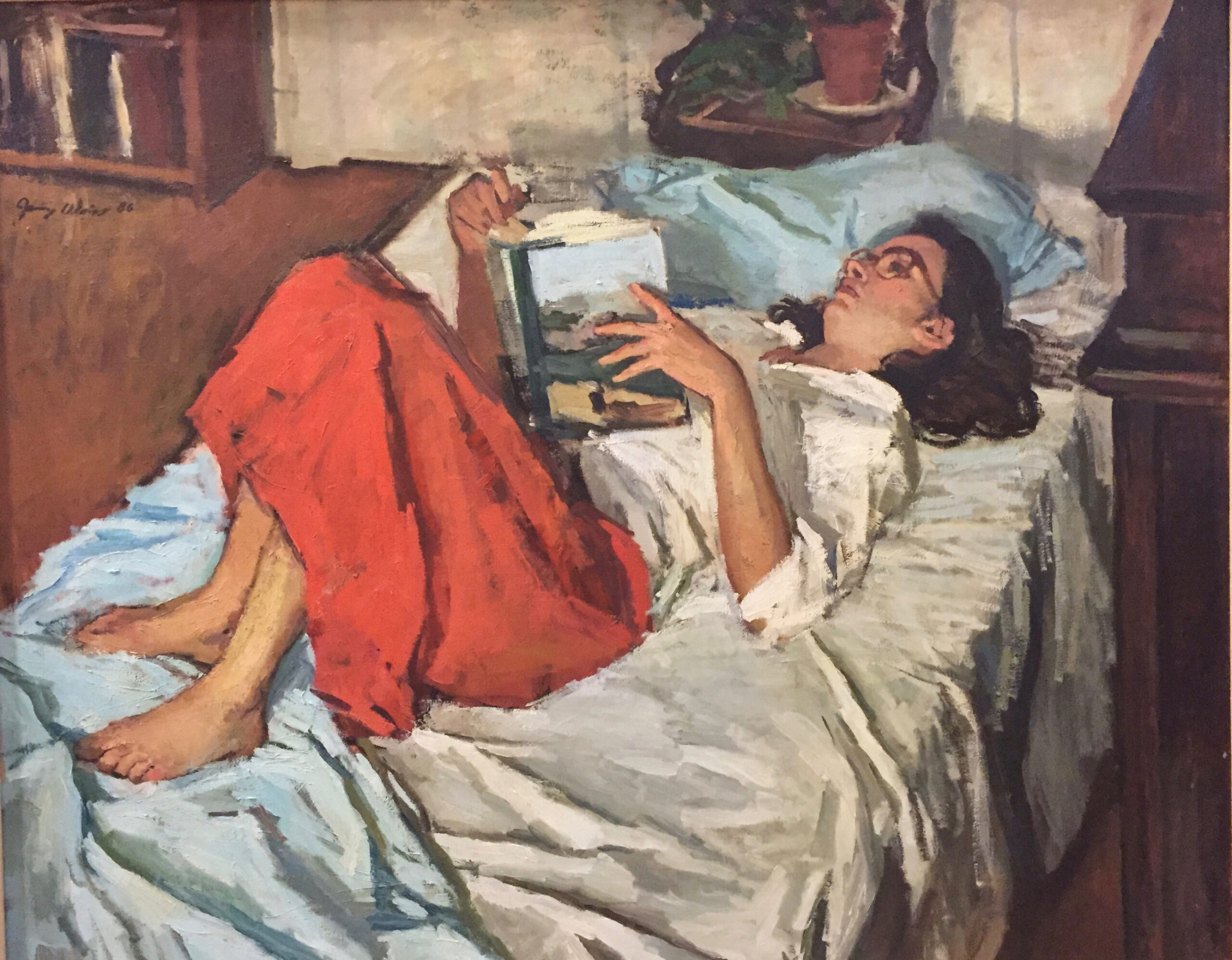

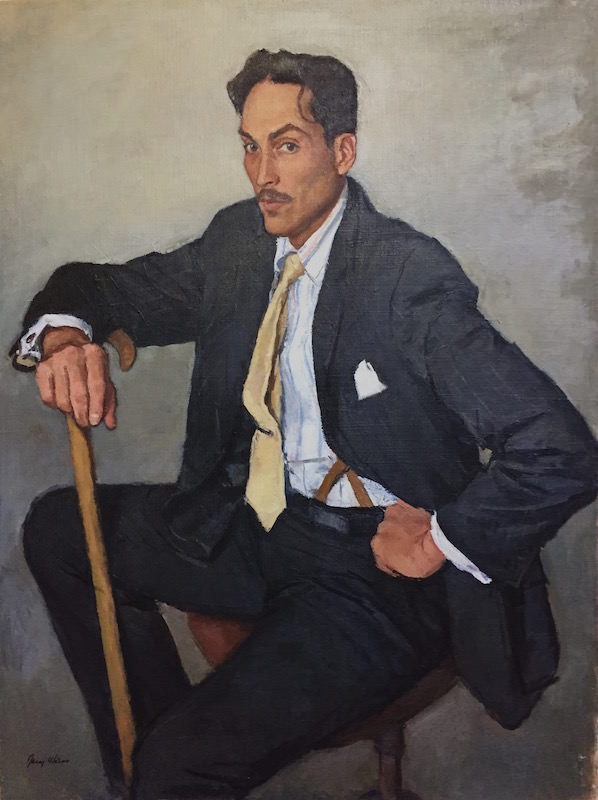

We sat for one another on several occasions, an arrangement that, given his looks, always fell in my favor. The first time was when we were twenty-one and twenty-two, respectively. In the mornings I’d drive from Jersey and through downtown Manhattan traffic to reach his top floor walk-up near Pratt in Brooklyn. Sometimes Dave would be hungover or asleep when I arrived. The walls of the apartment were painted dark gray to eliminate reflected light, and amid the gloom I painted him seated in a charcoal overcoat. The radio was tuned to urban dance music, a genre outside my experience, but a few of the songs are still in my head. It was hard work, and we spent hours together several days a week in common purpose. One day when progress seemed within my grasp but slipped through my hands I cursed, kicked his easel and threw my brushes. Dave was as close to being cross with me as I’d ever seen him. “Hey, easy. You had it before, you’ll get it again.” A few years later the painting was bought by Robert Rubin, then of Goldman Sachs and later the Secretary of the Treasury.

In the years immediately after leaving the League, I detached a bit from Manhattan out of preference for domestic life in New Jersey, but when my girlfriend left me and a subsequent affair fizzled, I spent my days at Union Square, where Dave and other painters had studios. For three or four years in my early thirties I knocked around with a group of fellow male artists; in retrospect it was a textbook lesson in arrested development, equal parts fun and misery. There were holiday dinners celebrated in diners, or sometimes at Dave’s mother’s apartment. This was a lonely stretch made tolerable by camaraderie, and I’d often hang out at the studios late into the evening, Dave patiently rolling cigarettes for himself with his long fingers while we talked, or whiling away hours throwing darts before driving home. Those stubbornly unattached years could have been a period of profligate misbehavior; instead I threw myself into painting. Dave advised me in the romantic arts, a humorous endeavor at a time when I avoided intimacy with stubborn and nearly ascetic resolve. There is no adequate description in the English language for the strangeness of several double dates he engineered on my behalf.

We painted together along the East River a few times. Once while I painted him as he stood working under the FDR Drive, a raucous bunch of teenagers paid a visit. Dave instructed me on how to disarm a malevolent group with swift and sure employment of a tee square, an antiquated notion in a gun-happy culture. We both had paintings accepted into National Academy annuals, and his, a dreary and powerful view of the Philadelphia train station, was favorably mentioned in a New York Times review. (He also took a trans-Canada train trip during the winter, and painted the stations at various stops. He told me he painted outside using auto antifreeze as a medium). One summer he invited me to accompany him to Sag Harbor; either on that trip or some other I painted him while he stood painting on a beach. The exact circumstances of our travels have blurred with time.

In 1994 I left both the studio at Union Square and the New Jersey apartment and moved to rural Connecticut. I severed friendships, and cut off from Dave. Any further news came by way of mutual friends. Within a few years I heard that Dave had married. Later on he became president of a New York arts club, taught painting in New York and New Jersey, and assisted Ray Kinstler in his workshops. He continued taking portrait commissions, traveled widely, and spent time in Maine. Simultaneously we each settled into parallel versions of a respectable middle age. Younger artists who met him after he’d gained weight and gravitas wouldn’t recognize my thumbnail descriptions of the man I knew so well in younger days, who was hell on wheels. With jet fuel.

On September 1, I got a message from a friend that Dave was declining rapidly. I knew that he’d received chemotherapy in the past year, and found pictures of him on social media, which showed him looking distressingly gaunt. I called him the next day, with trepidation over my sense of guilt and the fear that he’d be angry; it had been twenty-three years since we last talked. He apologized to me for saying anything that may have hurt my feelings all those years ago. I told him he had nothing to be sorry for and apologized to him in turn. I was told that he was moved by our conversation. I know that I was.

I learned of Dave’s passing on September 10, while I was returning to Connecticut after teaching my first class of the new school year at the League. The League is much the same now as it was when we studied there in the late 70s and early 80s, but it’s also different. There are far more women teaching, and there’s no longer a fourth floor smoking room or red sand buckets for cigarette butts hanging outside the studios. Now I take the elevators or walk slowly if using the stairs, and I remember when we thought nothing of running up and down the stairs from first floor to fourth. Full of youth and talent, we thought we owned the League, and I’m afraid there were times when we acted like it. Dave was a real New Yorker, and in all his flamboyance, incorrigibleness, convulsive laughter and memorable kindness, he was a quintessential part of League life. Even after all these years apart, he remains the most colorful person I’ve ever known, and I’m glad I did. Bless you, my old pal.