[1]

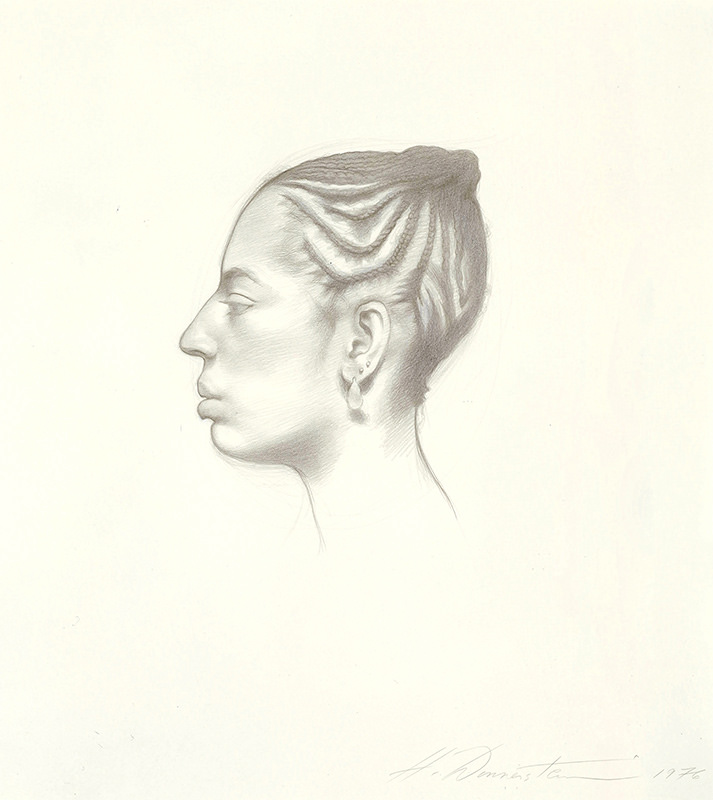

[1]The model sits within the frame with the formality and elegance of a Pollaiuolo.

They both have elegantly coiffed headdresses—each, very much of its time. Ralph’s massive, spongey dreadlocks place him as the latest in a line of men going back to the Kouros figures of sixth-century Attica.

[2]

[2]His dreadlocks have an elegant parting in the back. While the larger mass continues down the back like a horse’s tail, one bunch parts and wraps around the front, echoing the forward slant of the chest and beard. The whole mane looks like rushing water dividing to stream around a rock. This massive pile of hair casts a deep shadow along the model’s neck and back, while a single strand of dreadlock is silhouetted in the interstice.

They share, as well, the air of detached authority seen on Roman coins. As all portrait artists know, there is something solemnly ceremonious about the full-profile position. We do not make eye contact—that being somehow beneath the authority of the subject—just as the set mouth seems to be not just momentarily, but eternally, silent.

[3]

[3]One of the most intriguing parts of the drawing to me is the depiction of the headphones, which the artist has rendered so beautifully. We can easily date this to a pre-earbud era, when wearing headphones was more of a cumbersome affair, and aficionados could probably identify the make and model. But look at how beautifully the headphones are incorporated into the totality of the head; the top of the head-set pushes down slightly into the mass of hair, making a slight interruption in the linear flow of the hair, while the lower dreads cascade over the back of the earpiece. And the wire going down from the bottom of the earpiece is depicted at the same angle as the larger dreads, making the whole device look like an organic part of the head. In 500 years, will anyone know what these things are? And even if someone told them what they were, will anyone know what music meant to us in the early twenty-first century? How each of us has developed a soundtrack to our own lives and is enveloped in sound at all times of the day and night? How headphones seal us off from others in order to provide us with a private auditory world that allows us to sustain or change our mood at will?

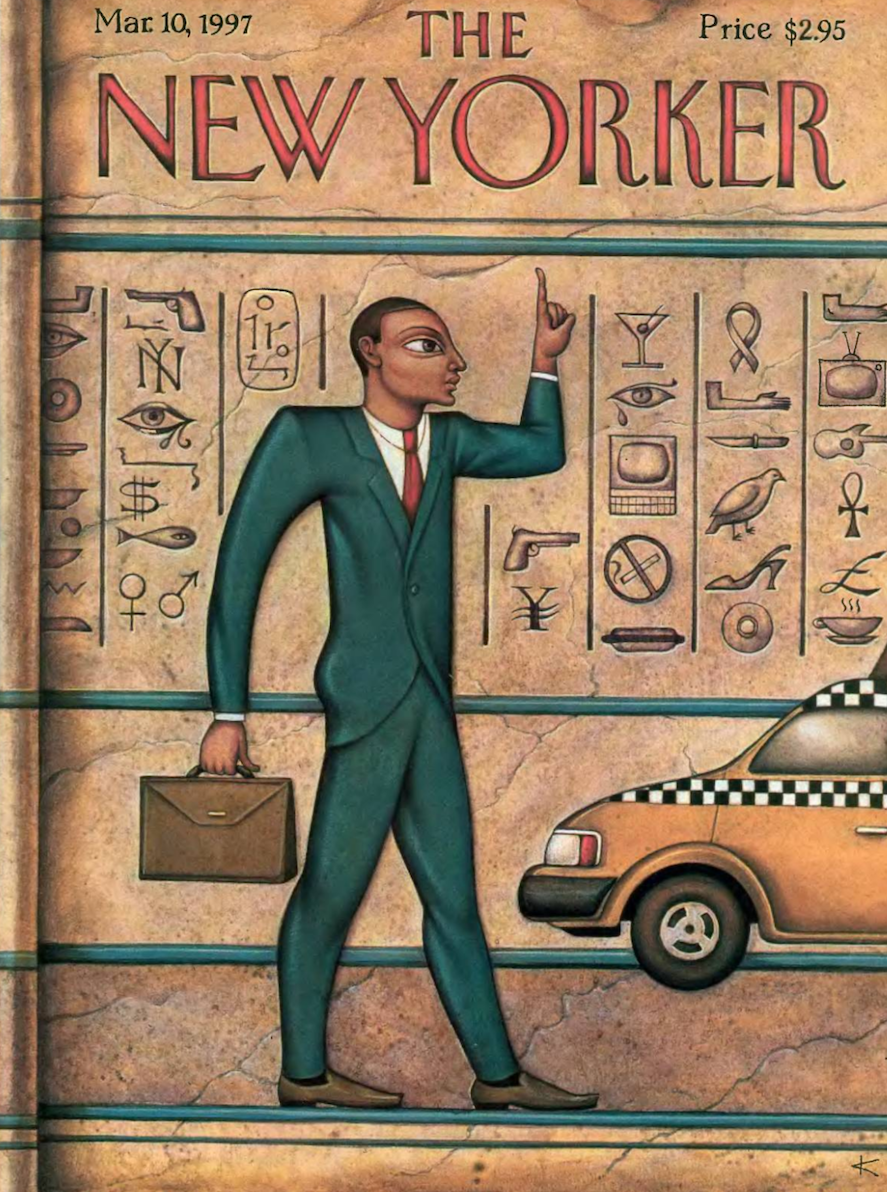

Iconographic elements like this are obvious to contemporary viewers, but will most likely need to be explained to viewers of future generations. We are quite comfortable having informed art historians explain the meaning and significance of objects, costumes and gestures in Egyptian, or Carolingian, or even Italian Renaissance art to us. What doesn’t occur to us is that in 500 or 1000 years, future art historians will be called upon to explicate our own objects, costumes and gestures similarly. This New Yorker cartoon makes the point beautifully.

[4]

[4]This cartoon presents us with a delightful confluence between the past and the present. We know precious little of what is going on in most Egyptian wall friezes. Who are these people? what are they doing? What do the hieroglyphics mean? But in this cartoon, we know exactly what is meant; the man is an upper class New Yorker, on his way to work, briefcase in hand, and he is hailing a taxi cab. On the wall behind him, we read pictograms for the New York Yankees, a martini, breast cancer awareness and a hot dog, among many others. The idea that these would need to be explained to people seems laughable to us, because they are so apparent to us.

A further point that may or may not be apparent to most viewers is that the headphones in Diego’s drawing are not only a part of late twentieth-century material culture, they are also an artifact of posing. In other words, the model, having to sit still for long periods of time, relies on his ability to listen to music to help him sit still. They are, in this way, analogous to the sticks and ropes used by academic models in more strenuous poses. Diego has managed to combine a portrait, an object of contemporary material culture and an artifact of posing into one seamless, integrated statement.

The drawing has a rich range of tonal value, from the white of the paper to the velvety dark shadows beneath the hair, to the myriad half-tones throughout the head. The form is carved by exquisitely graduated tones that make the shapes of the head either turn, come forward or recede. To fully appreciate just how tonal/painterly this drawing is, compare it to a similarly formatted profile portrait, Harvey Dinnerstein’s iconic silverpoint portrait Mercedes.

[5]

[5]Harvey’s drawing is a magnificent linear statement. By linear, I mean Heinrich Wölfflin’s sense that the beauty of things is first seen in the outlines. The eye is induced to feel along the edges of the form, which provide a fixed boundary. Look at the single beautiful line running from the top of Mercedes’ hair all the way down the profile nose, the lips, chin and finally neck. It is a track running evenly around the form, to which, as Wölfflin says, “the spectator can confidently entrust himself.” The firm and clear boundaries of solid objects give the spectator a feeling of security. Furthermore, everything is drawn with a uniform distinctness.

Diego’s drawing is seen much more in masses. The emphasis retreats from the outline into the interior masses, which are modeled in patches of adjacent tone. The drawing is dominated by lights and shadows, without stress on the boundaries, which have ceased to exist as a uniform sure guide. Furthermore, there is no longer a uniform distinctness; the greying beard and the dreadlocks fade away into indistinctness and evaporate before our eyes, giving the sense that the drawing has been magically conjured. There is no escaping the fact that Harvey’s drawing is done in silverpoint, which is a decidedly linear instrument, while Diego’s drawing is done in graphite, which has a much, much wider tonal range. But the fact remains that each artist initially selected his instrument with an aesthetic end in mind.

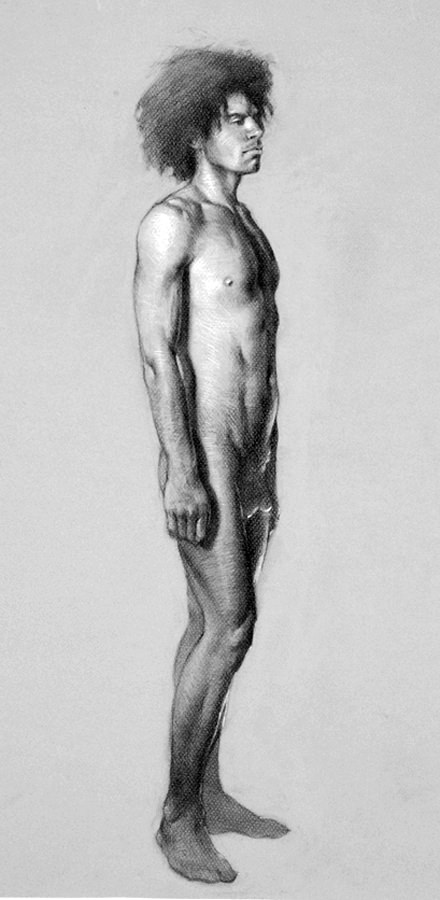

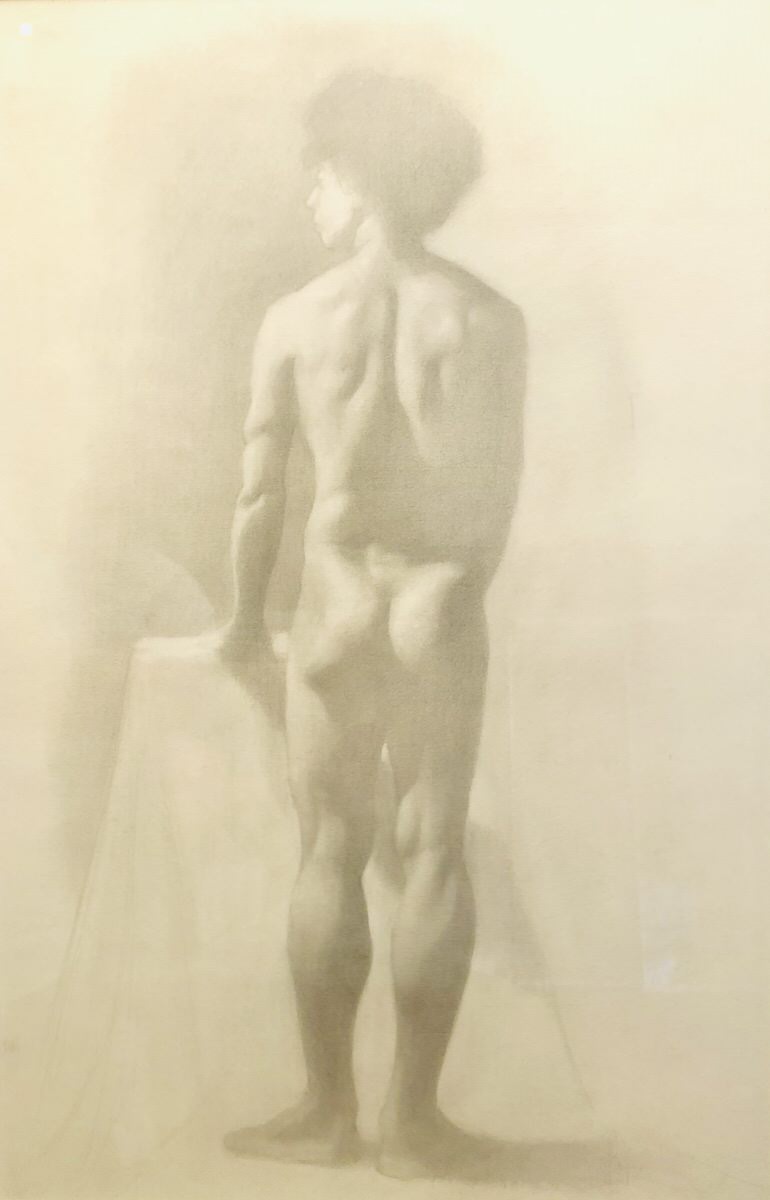

Diego’s graphic sense is decidedly tonal, as can be seen in his impressive Standing Male Figure.

[6]

[6]This figure is conceptually very strong: utterly tangible and solid as a rock. There are, however, any number of decidedly optical elements in the drawing as well. Anyone who has spent time studying models posing in art schools will recognize them immediately. The major light is from the upper right side of the figure. But so that the shadows do not get too dark (and so that the students on the other side of the room can see) there is a secondary light on the other side of the room which translates as a delicate reflected light on the belly, groin, and back thigh of the figure. In addition, as frequently happens, the spread of light from the spotlight is concentrated most strongly on the head and chest, and slowly fades as it moves down the figure. As a result, the lower legs and feet are decidedly darker than the upper part of the figure. Furthermore, there is a strong sense of looking straight at the head, but down at the feet. Proportionally, the figure gets smaller as it moves down, away from the eye. This is a purely optical phenomenon, one that gets corrected in more conceptual, classical schemes.

[7]

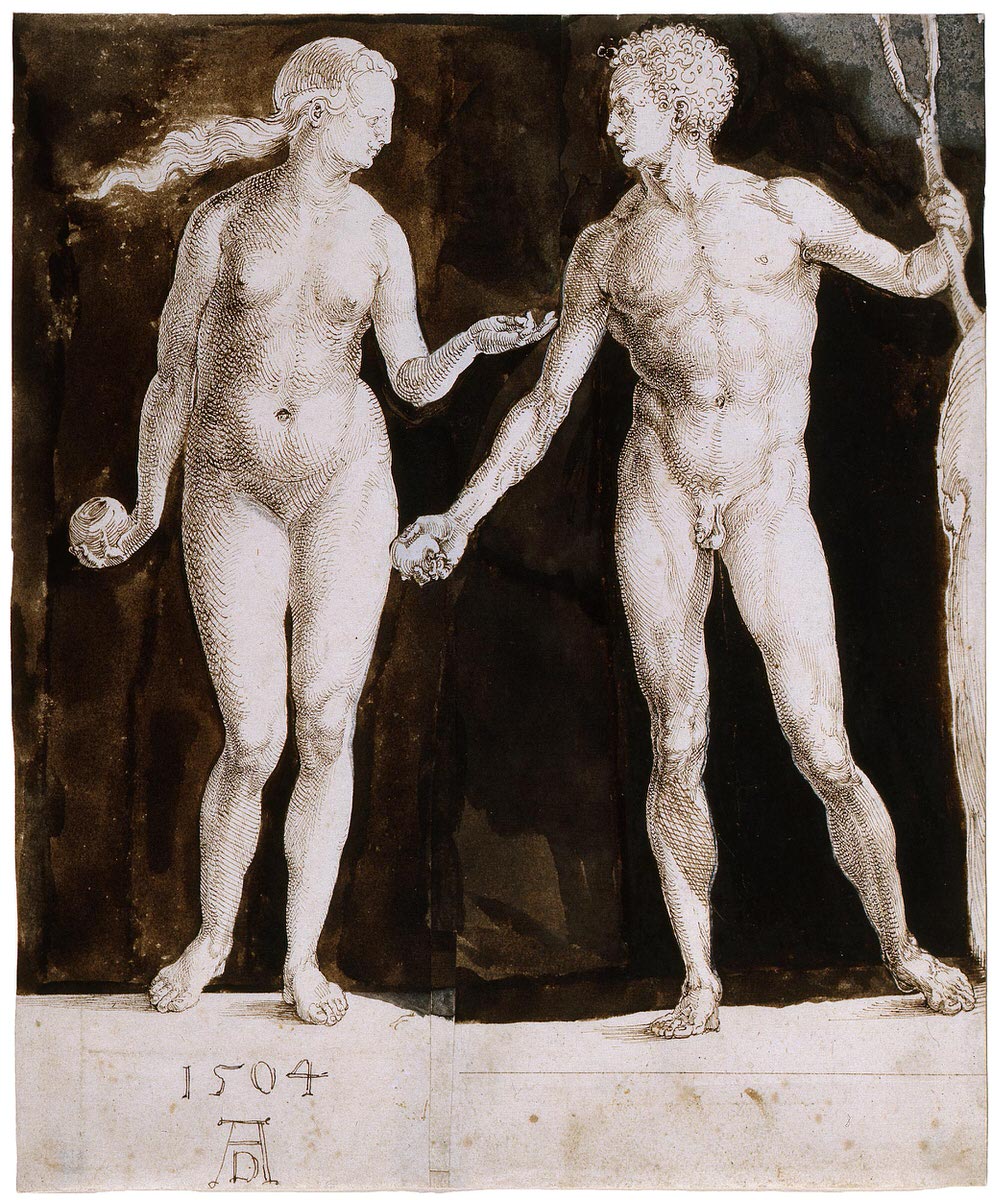

[7]In Dürer’s conception of the figure of Adam, we are clearly looking straight at the head and straight at the feet! In fact, we are looking straight at every part of the body. The artist accomplishes this by continually moving his eye level down as he moves down the figure. In addition, in Diego’s figure, the sense of the feet being far away is enhanced by the fact that the feet are modeled much more simply, with fewer details. Compare the front foot to the hand in terms of detail. Most surprisingly, the back foot is nothing but a silhouette, a simple flat shape. This movement from rendered form to flat shape is a key component in all of Diego’s drawings, and when he gives over to this play of form-ful and flat, the results are extraordinary.

[8]

[8]One of my favorite of all of Diego’s drawings is another full length standing figure, this one in my own collection. The drawing is on my wall, and I have studied it continually over the years.

The drawing has a sheen and a delicate glow, like looking at a silver chalice. It is an incredibly luminous drawing that gives off an extraordinary amount of soft light. On a scale of one to ten, the darkest dark is perhaps a four. If drawings could speak, and they do, this one whispers, as if it is speaking to you, and to you alone. Its lustrous quality is reinforced by the fact that there are no lines in the drawing, only tones. The tones have been so softly and thoroughly stumped that they seem to appear and disappear right in front of you. Unlike the other standing figure, the head in this drawing is barely blocked in, so as not to call attention to itself. He doesn’t want to distract you from the locus of the drawing, the main event, which is the thorax of the figure, from the trapezius down to the bottom of the gluteal region. In this area, there is a constant play of rounded forms emerging from flat masses that is breathtaking to behold. He does this by marriages—combining any shadow areas of tone that he can into flat fields that act as foils for the forms that arise out of them. The academic schema feels the need to describe form everywhere, whether it sees it or not. But the purely visual acknowledges that nature also presents us with areas that flatten out into mystery. It accepts these flat masses only to let the next form arise from them like a geologic form issuing from the sea. I have looked at this drawing continuously for almost two decades, and it never fails to delight.

[9]

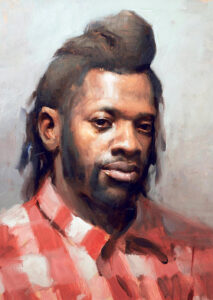

[9]I would be remiss in not touching on how this optical, painterly quality translates into Diego’s painting. His masterful oil study of the model Tyrone remains one of the strongest portrait heads created at the League in my time.

Solid and liquid at the same time, the head breaths life and air and bears an absolute resemblance to the model that continually startles me, having worked with Tyrone in many of my own classes. And while the drawing was the product of dozens and dozens of hours of work, the painting was painted quite quickly, which accounts in part for its lasting freshness. The League is fortunate, indeed, to have one of Diego’s works in its permanent collection.

Ephraim Rubenstein (@ephraim_rubenstein[10]) is an instructor at the Art Students League of New York.

- [Image]: https://asllinea.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Diego-Ralph-copy.jpeg

- [Image]: https://asllinea.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/786px-Piero_Pollaiuolo_001-1.jpg

- [Image]: https://asllinea.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Kouros-Dreadlocks.jpg

- [Image]: https://asllinea.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Screen-Shot-2021-02-07-at-9.34.27-AM.png

- [Image]: https://asllinea.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Harvey-Dinnerstein-_Mercedes_-silverpoint-on-clay-coated-surface-20-x-20-p.jpg

- [Image]: https://asllinea.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Standing-Male-Figure.jpg

- [Image]: https://asllinea.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/durer_i.jpg

- [Image]: https://asllinea.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Diego-Standing-Male-Nude-II.jpg

- [Image]: https://asllinea.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/retrato-pintura-tyrone-cuadros-dibujo-diego-catalan.jpg

- @ephraim_rubenstein: https://www.instagram.com/ephraim_rubenstein/?utm_medium=copy_link