Edward Hopper’s New York was recently installed at the Whitney Museum of American Art, where it will draw crowds until March. Hopper, in all his cool formulation, is hot again; in truth, his reputation hasn’t waned in a hundred years . The exhibition is a natural: Hopper lived on Washington Square for more than fifty years, and at over 3,000 items, the Whitney’s collection of his work is by far the deepest in the world. This is the third Hopper show I’ve seen at the Whitney since 1980. The first, a major retrospective, went over my youthful head; the paintings struck me as workmanlike, lacking passion. My bad. An exhibition in 2013 was a minor revelation of the power and flexibility of his draftsmanship, and a tutorial on process. The current show draws extensively from the home team, and also borrows from other major museums.

Hopper was born in 1882 in Nyack, New York, the son of a successful dry goods merchant. He drew seriously, early, and began a long course of study in New York City in 1889 with William Merritt Chase and Robert Henri. Hopper later claimed it took him ten years to get over Henri’s influence. Eventually he did, though his small Monhegan paintings, perhaps his last juicy oils, show that the influence wasn’t detrimental. In 1905, he started doing freelance illustration to make ends meet, a routine he came to dread. Illustration may have taught Hopper the assets of terse design, but his commercial work was decorative and largely devoid of the solid forms he valued. Besides, illustration puts a premium on movement, which was not what Hopper was about. It is a minor miracle that twenty years of illustration work didn’t wreck him as a painter.

Hopper traveled to Paris three times and adopted a more luminous palette. He moved to an apartment on Washington Square in 1911. Between 1915 and 1923, he created about seventy etchings. In 1924, he married fellow artist Josephine Nivison, who would sublimate her career on Hopper’s behalf (She insisted on being his only model, and thereon the women who populate Hopper’s work are variations of Jo). That same year, he sold out a show of watercolors. Encouraged by the sales, Hopper quit illustration to do his own painting full-time. A critical rave, “What vitality, force and directness! Observe what can be done with the homeliest subject,” sounds a lot like the initial reception accorded Winslow Homer’s work. Buoyed by lucrative museum purchases and a solo show at the Museum of Modern Art in 1933, Hopper’s rise thereafter was unabated. He and Jo took a summer home on Cape Cod and traveled the country by automobile, but New York remained home until his death in 1967. Much of Hopper’s best painting was inspired by what he saw within a few miles of the Washington Square studio.

The exhibition is comprised of seven sections that take a non-linear path, moving through media, theme, geography and meaning: The City in Print; The Window; The Horizontal City; Washington Square; Theater; Reality and Fantasy (to me, The Window Redux); and Sketching New York. I’m going to approach it as a practicing artist, via four media: etching, watercolor, drawing and oil painting.

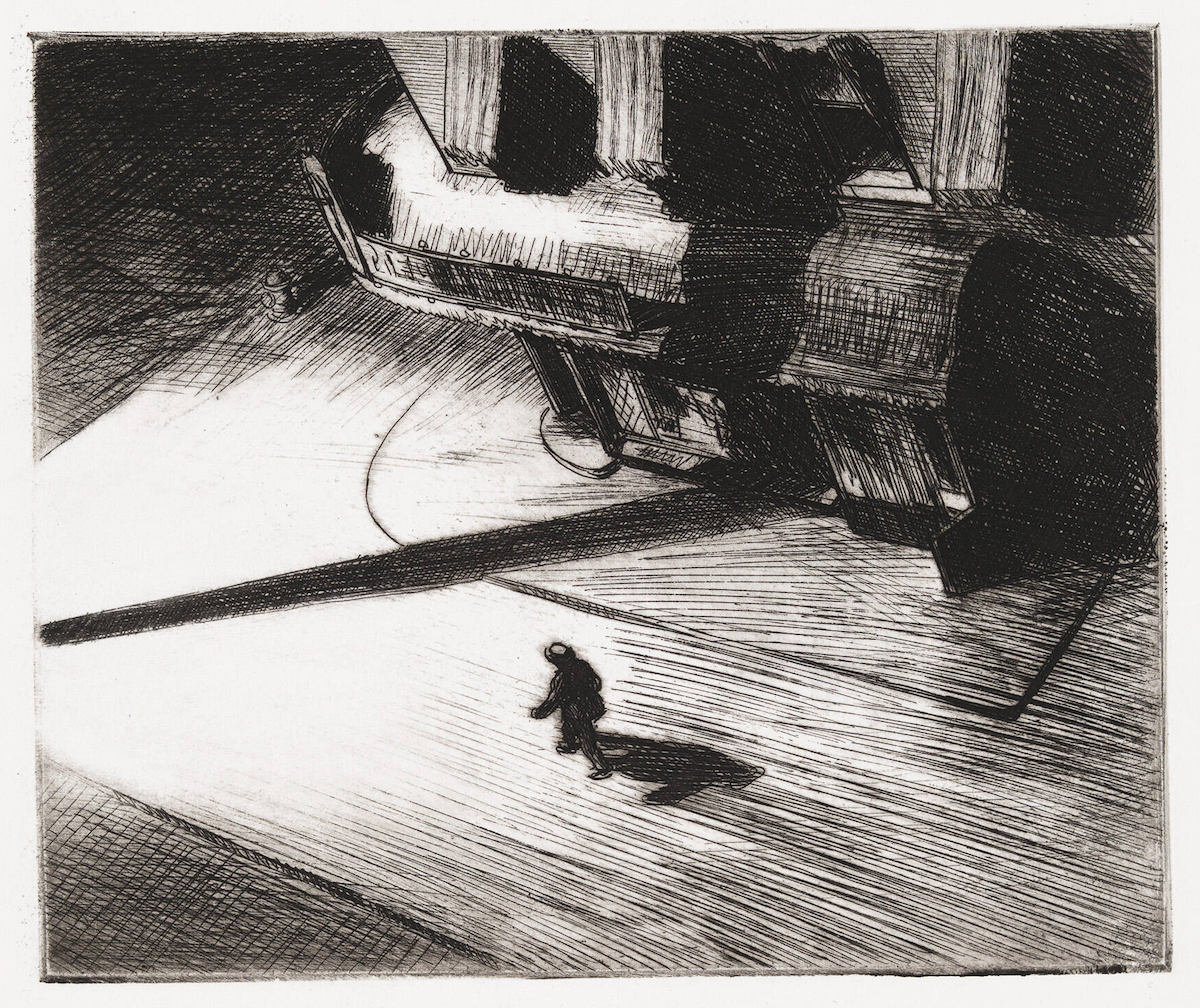

In the 1920s, before he was recognized primarily for his oils, Hopper mastered both etching and watercolor. He took up printmaking in 1915, and was mentored in the medium by the Australian-born artist Martin Lewis, who later taught at the League. They shared an interest in dramatically lit city nocturnes. Works like Hopper’s Night Shadows, with its lone figure seen from high above—presumably we are looking down from an apartment window—have much in common with Lewis’s plunging perspectives. Lewis often showed figures in groups, whereas Hopper rarely did. Hopper’s handling of the medium is looser and more assured; there is air between his lines. Later, he denied Lewis as a teacher or influence, crediting him for assistance with “the purely mechanical processes, grounding the plates, printing etc.” Lonely House may share a superficial affinity with his former classmate George Bellows’s painting Lone Tenement, but its stripped-down design presages the mood associated with Hopper’s best-known works. Similarly, Evening Wind and East Side Interior are reminiscent of John Sloan’s tenement interiors, though again, their nonspecific narratives are unmistakably Hopperesque. The etchings represent some of his earliest ventures into the lighting and mood that would characterize his sparsely populated oils. They have a linear bite that would not be seen in Hopper’s work again; his drawings were usually made with soft pencils, charcoal or crayon, and aimed for a different effect. Fine as the etchings are, they were omitted from the otherwise comprehensive 1980 retrospective.

Hopper met Jo Nivison while vacationing in Gloucester, Massachusetts, in the summer of 1923. The Gloucester trip was Hopper’s first extensive foray in watercolor; he and Jo painted the town’s buildings and backstreets together. Like his etchings, the watercolors presage later canvases in some respects, in that they focus on the area’s venerable architecture, hard edges and strong sunlight effects. Not surprisingly, they differ from the oils in their spontaneity and luminosity. They are field notes, reportorial works in the best sense. It would be two years before Hopper used watercolor for scenes of Greenwich Village. The results were exemplary. Skyline Near Washington Square, Rooftops, Roofs, Washington Square and My Roof highlight Hopper’s deadpan compositional sense, a gift for fragmentary views that exploit the staccato rhythms of the city’s mundane rooftop pipes, chimneys and water towers silhouetted against the sky. Moreover, watercolor allowed him to balance sharp draftsmanship with a free application of transparent pigment. Rather than evolving toward a freer approach, after 1930 the watercolors became progressively tighter and drier in handling. The New York works include some of his best in the medium, and they rank among the best watercolors by a twentieth-century American painter.

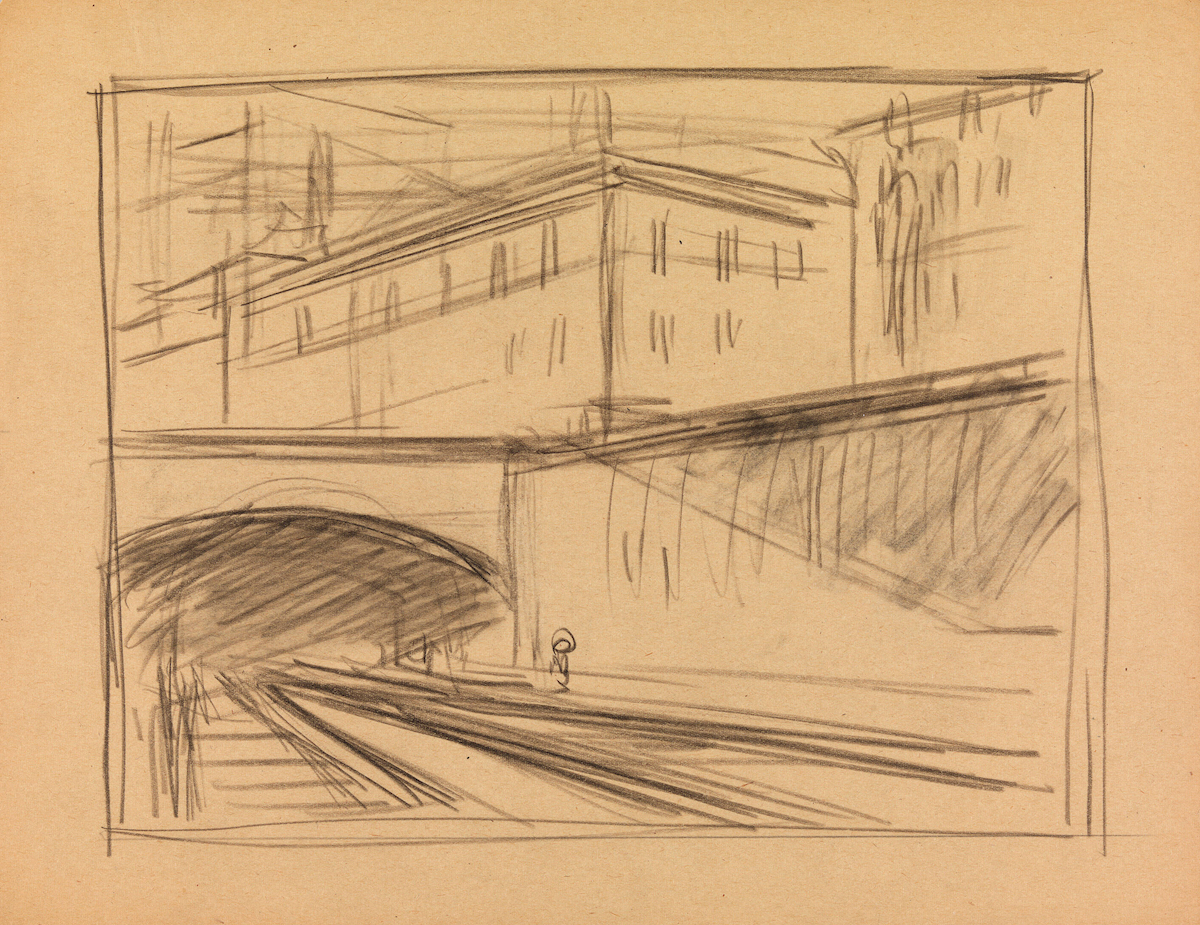

The drawings were often field notes, as well, though they usually served a utilitarian purpose as preparatory studies for oils. Some drawings, like Study for Williamsburg Bridge, were done on site with meticulous attention to detail, which Hopper relied upon as a primary reference for the studio painting. A later sketch, Study for Approaching a City, was drawn with greater gestural brevity; while it, too, was used as source material for a painting, it reflects Hopper’s transition toward less specific subjects. The titles of the paintings suggest as much, moving from the particular to the generic. With its broad sweeps of chalk and powerful rectangular grid, Study for City Sunlight is even more forceful. Hopper was no longer making a detailed blueprint, but setting down essential pictorial structure; the painting follows the drawing’s design, but exchanges brutality of execution for nuance. Morning Sun was painted at about the same time, and was preceded by a series of drawings for which Jo modeled. Each served a different function, and one (in the Whitney’s collection but not in this show) is especially notable for what it tells us of the artist’s methods. It is a life study of the model, surrounded by two dozen written notations, each connected to a part of the figure by a straight line. These are color notes, intended as guidance for the painting and freeing the model from further hours of posing. This is worthy of a brief digression.

Although the process of amassing preliminary drawings from which to construct a studio painting was a long-standing tradition, it was an increasingly neglected practice by the mid-20th century. Hopper’s adherence to the routine reflected a lifelong determination to rely on draftsmanship and visual memory, rather than photographic reference. Certainly he possessed the skills to set down drawings that would be functional. He must also have cultivated the ability to recall what he had seen. Hopper’s city paintings are riveting not because they are photographic or illusionistic—quite often they’re inventions depicting nonexistent places—but because they are highly developed expressions of his imagination that appear entirely credible. He once explained that his aim was to “project upon canvas my most intimate reaction to the subject as it appears when I like it most; when the facts are given unity by my interest and prejudices.” That conclusion bears repeating: when the facts are given unity by my interest and prejudices. More pointed was Hopper’s response to a neighbor who encountered him sitting in the park. “I’m thinking out my picture.”

There are too many good and great paintings in Edward Hopper’s New York to list, so I’ll mention a few, following a chronological order. New York Corner (1913), a French-inspired study of urban patterns, clothed in atmosphere. The mood reminds me of my first winter in the city. Girl at a Sewing Machine (c. 1921) is an early venture into the solitary figure, warmly lit and activated by the red interior. It’s a reminder of how important color was to Hopper. New York Pavements (1924), would just be a mesmeric study of a building facade, were it not for the inexplicable inclusion of a nun pushing a baby carriage, her habit billowing behind her. The City (1927), in which geometry and atmosphere act as a platform for the juxtaposition of French and American architecture. Night Windows (1928), a view from one apartment window into another, announces the voyeurism of Hopper’s nocturnes. Manhattan Bridge Loop (1928), is a frieze of old New York. The red and brown brick fronts set against a pale blue sky was an idea crystallized to formal perfection in Early Sunday Morning (1930); the facade of Early Sunday Morning was in turn recycled as the backdrop for Nighthawks, an instance of Hopper slyly sampling his own earlier work.

Standouts among later works include the aforementioned Morning Sun (1952), and Chair Car (1965). Rigidity sets into his figures and the compositions sometimes look like self-parodies, as in Sunlight in a Cafeteria (1958) and Sunlight on Brownstones (1956), the latter confirming that Hopper had little feel for arboreal subjects; he was bedeviled by trees. The oils aren’t terribly rewarding from a tactile standpoint. After the pleasantly visceral Monhegan work of 1916-19, the paint application was dutifully checked for indications of exuberance.

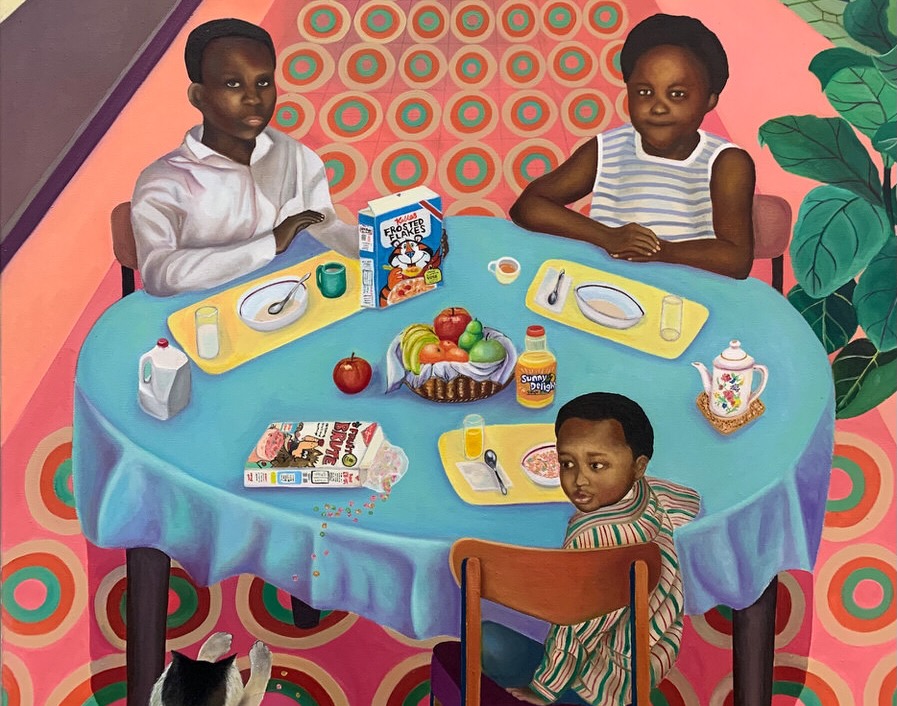

In the show’s catalogue, Kim Conaty, Steven and Ann Ames Curator of Drawings and Prints, identifies a troubling aspect of Hopper’s synthetic city views. Barely populated as his New York is, it is still undeniably a white city. That absence of cultural diversity has me thinking about Hopper’s immense popularity, and whether there’s a nostalgia at play that harkens to a New York that never was. For the casual museum goer, how much of Hopper’s subliminal appeal is for a city that is unrealistically desolate, clean, and, except for the occasional male/female encounter, free of human interaction, not to mention diversity?

For that matter, an artist who could paint City Roofs didn’t need to add people to the mix; the fact that he sometimes did makes his work more accessible to the public than that of the contemporary Precisionist painters. “Maybe I am not very human,” Hopper once said. “What I wanted to do was to paint sunlight on the side of a house.” Hopper’s city was reductive, stripped of noise and movement to its melancholic core. The brownstones and prosaic filigree that he painted still exist. Some ornamentation, like the spires that topped the newly constructed Queensborough Bridge in Hopper’s painting are long gone. At any rate, it wasn’t so much the grandiloquence of the city’s architecture that interested him. It is the solitude that exists in its shadows, that continues to intrigue.