Ira Goldberg: Before coming to study at the League, what was your experience of art?

Everett Raymond Kinstler: My earliest memories of art were during the 1930s when I was five, looking at illustrations from magazines and books in our New York City apartment. This was a time when there were hundreds of enormously popular weekly and monthly publications that were filled with reproductions by the leading illustrators of the day. My favorites were Alex Raymond whose Flash Gordon helped inspire the movie Star Wars decades later; Hal Foster who drew Tarzan and later Prince Valiant; and Milton Caniff, creator of Terry and the Pirates, which we jokingly referred to as “dysentery and the pirates.”

Each artist was a brilliant draftsman and superb storyteller, and their work greatly influenced my youthful appreciation as well as my artistic development throughout my career.

Later I discovered European illustrators like Menzel, Vierge, Edwin Austin Abbey (an American who lived in London), and especially the master delineator Gustave Doré.

I was also addicted to motion pictures. (Remember, television didn’t exist yet.) Movie storytelling has had a deep effect on my creativity and imagination throughout my career. A kid in love with the movies, I had no idea that almost forty years later, I would paint from life many of the major movie stars I had seen on screen.

How did you come to consider a career as an artist?

When I was thirteen, I was fortunate enough (or so I thought) to be accepted into the famous High School of Music and Art (now La Guardia High School), a school for gifted children. This was a time when abstract art was “in” and classical drawing was out of vogue. My interest in realistic drawing and illustration was discouraged. My grades dropped. I was extremely unhappy.

Midway through my second year, I transferred to the High School of Industrial Art (now the High School of Art and Design), a vocational school, a no-nonsense institution that focused on the working techniques that a young artist needed to find a job and earn a living. I learned the basics that illustrators needed to know, such as ink drawing with pen and brush, scratch board drawing and lettering, and various reproduction methods used to print and reproduce art in books and magazines.

Prior to my sixteenth birthday, I made a decision that was to shape the rest of my life. I decided to leave school and try to enter the professional art field. Looking back, I realize I was consumed with the desire to make my living with art. Fortunately, my parents seemed to understand my passion for art and my unhappiness in school. My father’s remark at this time was, “You’re a lucky young man: you’ll be able to earn a living doing something you love. Don’t ever forget it.”

What kind of work did you pursue?

I wish I could say it was talent that landed me my first salary, but it was simply the shortage of manpower during World War II. Almost every man over age eighteen was in the armed services, which meant there were vacancies in the job market. So when I answered a newspaper ad for “a comic book inker’s apprentice” at a salary of $15 for a six-day week, I was hired. I was sixteen years old.

I would ink about thirty panels daily, so in a six-day week I inked one hundred and eighty panels. This routine sounds grueling, but I was simply caught up in doing what I loved. It was invaluable training for a young artist.

How did you come to the Art Students League?

While still a staff artist, one of the senior artists suggested I ought to have more formal art training, especially drawing from life, and he encouraged me to attend art classes. My next stop was the nearby Art Students League. I consider the League to be the gut of American art schools. Almost every painter, sculptor, and graphic artist prominent in this country’s art history has attended classes there. Its teachers are respected and revered and students can study in the most classical or the most abstract manner. I began attending evening classes with Jon Corbino, a regionalist painter with a strong sense of the figure. Working from life with nude models was challenging and exciting, and it showed me all too clearly how badly I needed more of this training.

While studying with Corbino, I saw a League instructors’ exhibition and was riveted by a handsome full-length portrait by Frank Vincent DuMond. Wonderfully sensitive and well-painted, I knew I wanted to study with this legendary painter and teacher. This proved to be another pivotal decision of my life.

At seventeen years of age, I entered DuMond’s class. I had no experience with color, nor had I ever used oil paint. My first attempt was a huge head, twice life-size, using solid black for shadow and mainly pure white for the light areas. As Mr. DuMond stopped at my easel to critique my efforts, I gestured like a traffic cop and blurted, “This is my first painting!” He put a gentle hand on my shoulder, looked from painting to me, and said, “No…really?”

You credit DuMond as your foremost mentor.

From the first meeting in 1944 until his death seven years later, DuMond was both my teacher and friend. An American-trained artist in Paris, he had known both Whistler and John Singer Sargent. DuMond was an excellent painter and an extraordinary human being. He had begun his career as a book and magazine illustrator and had developed into a fine portrait painter and muralist, becoming an important part of the American Impressionist school. A dedicated and influential teacher, his students included Norman Rockwell, Georgia O’Keeffe, and John Marin.

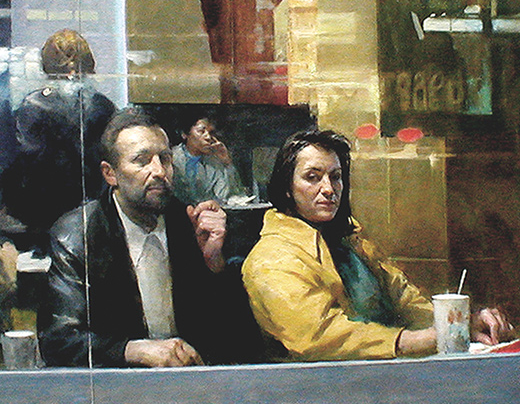

In the academic sense, DuMond was a traditional painter, with a remarkable ability to inspire the heart and stimulate the minds of his students. He believed in experimentation and curiosity…and discipline. Drawing and painting was a new, tremendously challenging and enjoyable experience for me, and I spent a fruitful year with DuMond at the League. In class, if some of us complained we couldn’t see the model, he would encourage us to move to a different location in the room and paint the space we could see, with the other students included. I always remembered that, and decades later, when I taught at the League, (in the same DuMond studio), I suggested that to my students.

Describe some of your interactions with DuMond that were particularly insightful.

I learned a valuable lesson from DuMond once when I was attempting a class interior. The studio was crowded and consequently so was my canvas, and I was struggling to create a convincing sense of space. DuMond took my brush and mixed a kind of “soup” with oil colors on my palette. He scumbled that “veil” of tone over the more distant areas of my canvas…and suddenly everything pulled together. A tonal painter, he explained how that middle-tone is so necessary to solidify a painting.

Later, when I went to paint with DuMond in Vermont—the first time I’d ever worked out of doors—he showed me the use of the “veil” in painting landscape. For the most part, the grass on the mountains was green, but appeared blue-grey at a distance. DuMond’s approach was to scumble a middle tone over the distant mountains to create a sense of space, atmosphere, and cohesion, making the painting more compact and solid. DuMond spoke endlessly about halftones, those silvery edges where light meets shadow on a head or figure. He suggested that transitions were cool—he actually called them “silver”—teaching us that middle tones, not the lights or darks, are what hold a picture together.

Frank DuMond’s influence on me was profound. He encouraged me and took constant interest in my development. The most important thing he said to me was, “I am not trying to teach you to paint, but to observe.” Now as I write about him, almost sixty years later, I still feel deep appreciation for his gift to me.

At what point did you became good enough to be a staff illustrator?

While studying with DuMond, I was freelancing, doing comics and then pulp magazines at eight dollars a piece.

How did you develop your drawing ability?

I worked very hard. And I loved it. I was doing pulp magazines, the comic strips, and occasionally I’d get some advertising jobs. I was basically self-taught. But I was studying from life, painting and drawing from life every afternoon.

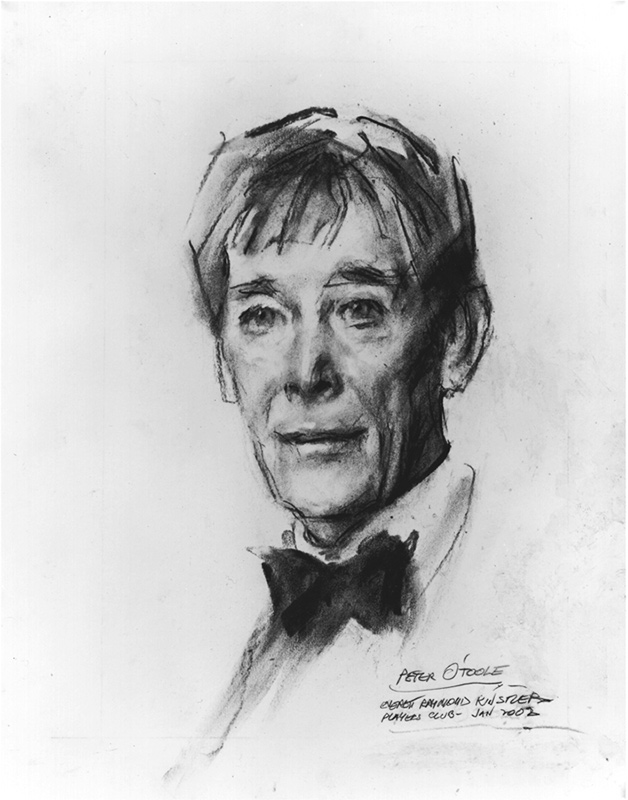

I met James Montgomery Flagg when he was sixty-seven and I was seventeen. Flagg was the most popular illustrator of his day. A student of Twachtman and DuMond at the League, his “I Want You” poster of Uncle Sam was famous. Flagg used a lot of expletives and was very opinionated, asserting, for example, “Art can’t be taught.” I showed him my illustrations. He said, “Young fellow, you’re doomed to be an artist.” He was very complimentary, which was unlike him. He asked me, “Where are you studying?” I told him, “At the League with Frank DuMond.” “Frank DuMond,” he said, “That old bastard? He’s still alive? I studied with him fifty years ago.” When I next saw Mr. DuMond, I told him I’d met Flagg. He replied, “Oh, yes, he was one of my boys.” I never forgot that—“one of my boys.”

Men like DuMond weren’t specialists, and they didn’t talk about classicism, though they worked within the tradition. I believe that an artist must reflect his time. Many of the illustrators, like Dean Cornwell, who trained at the League, were wonderful draftsmen and wonderful painters. DuMond knew how to form pictures compositionally because he’d worked as an illustrator. He was a storyteller and a great muralist. He was also very much of the earth. We would take evening walks with him in Vermont, and he would look at the silhouettes of trees, thinking and talking painting all the time.

I was drafted and during my army service Mr. DuMond wrote me often, his letters filled with warmth and encouragement.

You never went overseas?

No, I was stationed in New Jersey. On terminal leave just before my discharge from the service, I walked up to the League into Mr. DuMond’s class, in Studio 7. I can’t articulate what I felt, but it was a sort of bittersweet feeling. Then I walked right out. You can’t go home again.

How did you forge a career after leaving the ASL?

When I was discharged, I moved into a tiny maid’s room in my parents’ apartment on West 90th Street. There was just enough room for a drawing board and a chair. I began selling pulp illustrations, which was a wonderful training ground. Like an actor in summer stock, you learn your trade. I really learned to draw. DuMond called me one day and said, “There’s a studio at the National Arts Club.” It was about $50 a month, and I took it. I saw Mr. DuMond every day, and he was available to critique my work.

Who else influenced your draftsmanship?

This is a question I’m frequently asked. Recently, at a comic book convention in San Diego, I was speaking with some graphic artists, very nice guys in their 30s and 40s, who are making a lot of money drawing graphic novels. Appreciative of my early illustration work, they asked me, “Where did you learn to draw like this?” I told them, “In art school life class.” “Really?” was their response. We learned by osmosis. Everyone around me was stimulated. We had all these masters to look up to—Hals, Velázquez, Degas, Vuillard, Monet, Sargent, Serov. And then there were the contemporary artists and the book and magazine illustrators to see and admire. For the most part, these artists had studied with Robert Henri and William Merritt Chase. They were trained to paint landscape and the figure, and they could draw. Those that couldn’t sell their paintings, turned to illustration. Their output was awesome…the ethic was devotion to craft and hard work…they had individuality, personality, and were wonderful technically.

So many turned to illustration out of economic necessity. How difficult was it to earn a living?

There was a market for it then. Once you learned your craft, you could find many outlets. We enjoyed what we did, the visual storytelling. But there’s just no market today.

What about comics and graphic novels?

I’m not one of those people who say the old days were better. I think careers in illustration nurtured some extraordinary people because, like actors back then, they worked every day. How can you grow as an artist unless you live it and breathe it and you do it all the time?

I don’t disagree. What I’m curious about is your opinion of the methods of contemporary illustrators who work for, say, DC or Marvel comics.

Everything is being computerized. Back when we created our comics they were black and white, and were hand-colored and then processed by a printer where the ben-day dots were dropped in. Today they’ve got four-color presses where artists work in full color. It’s all digitized. Years ago, Roy Lichtenstein said to me, “Ray, you were pop art!”

There are some very talented people today, but few natural draftsmen who can draw well. Milton Caniff was to the comic strip what Orson Welles was to the movies when he did Citizen Kane. He revolutionized the way of looking at comics with a modern eye and approach.

When you first started at the League and were involved with drawing comics and pulp illustrations, you hadn’t seen art before. You hadn’t ever visited a museum.

Not until I met DuMond. He got me going to the Met, which is where I discovered Velázquez and Frans Hals and the great painters. When I was seventeen, I went to the Hispanic Society and saw Sorolla. That had an impact on my life that I still feel.

Those many trips showed me that these men were all trained to draw and paint from life. They were not stylists. They worked in landscape, etching, watercolor. Extraordinary. There is not one person living today in, say, portraiture who can touch John Singer Sargent. Why? Back then, artists trained their hands and minds. Also they didn’t contend with the distractions we do. People wrote letters in those days. We pay a price for xeroxes, e-mails, other fast technologies, and sound bites…the quick fix.

If I had any flair and ability as an artist, it lay with interpreting people, whether the cowboy or the pretty girl. I called it “cowboys and cleavage.”

If you don’t use your natural talents, you’re not going to expand and challenge them. I see so many people today who are rediscovering good drawing, but it’s mostly emulative when it should, at least in equal measure, evolve out of the artist’s times. All of the artists that I like reflected their times. I mean, Sargent, Zorn, and Vuillard were twentieth-century painters.

Look at portraiture done today. Nobody ranks with Hals, Stuart, Raeburn, Reynolds, Van Dyck. I understand the difficulties. Portrait painters, like everyone else, have got to earn a living. They’re leaning on photographs and projection and not involving themselves with drawing and painting from life. There is no one who works with a camera who can touch what these men did with their naked eye. David Hockney’s claim that the old masters needed optic magnifiers is sheer nonsense.

Is the easy availability of these new technologies the reason why they’ve changed how artists make art?

Absolutely.

Technical virtuosity these days seems to be in the service of reproducing photographic effects in paint. Many artists seem to feel that making something look photographic is an end in itself, whereas I’ve always looked at a painting as exceeding the photograph in its ability to convey truth.

My own theory of art may be simplistic. I think great works of art are the result of valuable personalities. If an artist has got something to say, you’ll see it in his drawings and creative work.

This comes from observation, hard work, and no shortcuts. My friend Linda Davis wrote: “Realism in art must not be simply objective which is deadly, but must reflect the personality of the observer for that is what gives art and literature its uniqueness.”

I want to get back to your biography. How did you go from selling pulp illustrations into commissioned portraiture?

That was an interesting bridge. Put simply, working as an illustrator I was always doing portraits. If I had any flair and ability as an artist, it lay with interpreting people, whether the cowboy or the pretty girl. I called it “cowboys and cleavage.” Anyway, I sought to capture the individual. That was my hook. I loved it. To this day, I’m still totally turned on by the idea.

The main reason, though, was that when publications started to feature graphic design and photographs, the work dried up. Suddenly, even artists like Dean Cornwell, Rockwell, Whitmore, the Clark brothers, giants in the field, couldn’t get work.

My transition to portraiture was facilitated by many mentors, particularly at the National Arts Club. One was dear John C. Johansen, whose great portrait of Henry Clay Frick hangs in the Frick home. Johansen had been a student of Frank Duveneck and taught at the League in the 1920s. He was a great painter as was his wife Jean MacLane. I saw Johansen every day since he lived above me. He’d come down and comment on my work. I was intense and respectful, and he was trying to make me a better artist.

Friendships like this forge a kind of oral tradition and pedigree linking the generations, which is the backbone of art education.

The painter Gordon Stevenson, who’d taken classes with Sorolla in Spain and knew Sargent, was another of my mentors. Gordon would drop by my studio—he was well along in years, an elegant man, who lacked fire in his belly because he didn’t have to work for a living. He’d look at my work and begin his remarks with, “Now, Sargent told me that…“, or, “When I was with Sorolla…”

I wonder how the canon of Western art will fair in academia in the future. You sometimes hear all of Western painting dismissed as stuff done by European white males. Who will preserve this tradition? The museums? Artists?

There will always be people, like you and me, who can relate and appreciate and question.

Every day when I look at my work, I think about what needs adjustment. I want to get better. Commissioned portraiture can diminish an artist a great deal.

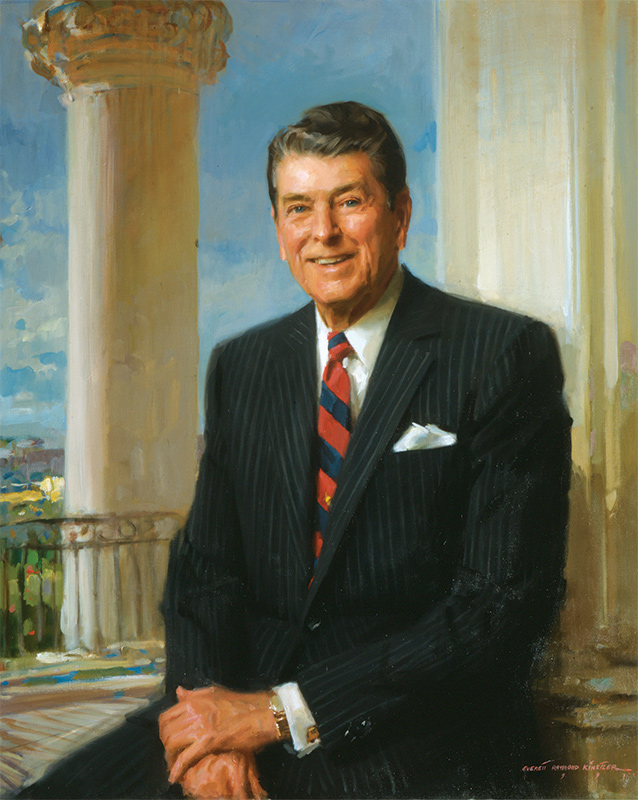

Let’s get back to your career. You’ve painted so many major figures. Your list of sitters reads like a Who’s Who. How did your popularity grow?

Rather than say I got popular, I think of it as getting busier. I loved what I was doing. But throughout I was still painting landscapes, figures, and interiors…personal work. I made sure that I continued to draw. I didn’t want to become a specialist. Specialists become mannerists.

To this day, I’m constantly studying. At my studio in

Connecticut, my bookcases are filled with thousands of books. There’s not a day that goes by that I don’t pull out a book to look at and study how the artists I admire treated this or that subject.

I do the same thing.

In our culture today, since the advent of television, this kind of single-minded focus and immersion is difficult.

Once television came in, the magazines folded. One of the most significant signs for me was when the Saturday Evening Post stopped crediting illustrators. I saw that kind of imagery, that kind of art, replaced by graphic design and lettering. I’m not going to say it was better or worse; it was different. I could’ve bitched about it, but instead sought out other outlets. As I’ve said, I enjoyed interpreting people through paint. Whatever I could do I did and never looked down on it. I worked hard, never flipped off assignments. Don’t ever reach a point that you’re not going to start over again, that you’re tired. This is a value I learned from my father.

It’s important to stay fresh. I used to tell students that it is as important to know why you don’t like something as much as why you like it. Every day when I look at my work, I think about what needs adjustment. I want to get better. Commissioned portraiture can diminish an artist a great deal. You repeat the same thing, over and over, not spreading your wings to fly.

How old were you when this cultural shift took place?

I was in my twenties, and had been working in the field for several years. I was moving between children’s books, paperback covers, record album jackets, enjoying it but not making much money. But I paid my rent. I worked every day because I loved working. Suddenly there were no illustration assignments. Magazines folded. The Saturday Evening Post folded, Colliers folded, Liberty folded.

Meanwhile, I continued to paint people. When I was about twenty-seven or twenty-eight, I took four or five portrait samples up to Portraits Incorporated. A young fellow named Forrest Mars came in. His parents wanted to give him a portrait for his twenty-fifth birthday. His father was one of the richest men in America. And I painted him, his wife, family, and children. And I kept on working, trying to improve.

Did your reputation just start to grow?

There were a lot of disappointments and rejections. I asked Katharine Hepburn once, “How did you plan roles that you didn’t relate to?” She said, “You do the best you can and you get on with it.” That’s what I did. I had no time to think back. I was married, I had children. Once, unable to find work, I was close to depression. I’d go out with my watercolors to First Avenue over by the river, just painting. For a time I was getting only a couple of jobs a year. It was barely enough to pay rent. So I went back and took some comic book work at a place called Classic Comics. They’d assign each artist a few pages to do rather than the whole story. They wouldn’t allow you to sign your work. It was demeaning.

Needing to earn a living, I’d do comics, an odd advertising job, and a portrait or two. I kept exhibiting though, with Allied Artists, Audubon Artists, the American Watercolor Society. The only gallery I had was Grand Central Art Galleries. I eked out an existence, paying the rent, enough to take care of my family and responsibilities.

Mr. Johansen wanted to propose me for membership to the National Academy. It meant something since Sargent, Chase, and Eakins had been academicians, as was Homer. I didn’t have time to think about the nomination; I had to work. I didn’t know how I was going to pay rent. I was working round the clock with coffee and cigarettes, meeting deadlines. The academy turned me down. Johansen felt worse than I did. I got a letter from Everett Warner, who was a member of the academy and good landscape painter. “Dear Mr. Kinstler,” he wrote, “I was very disappointed to see that you were turned down at the Academy. You’re a young artist of great potential and talent.” He continued, “Don’t be discouraged. The academy needs people like you.” It has always made me sensitive about writing to people.

I was turned down for academy membership four times. The last time it was suggested I apply as a watercolorist, since back then you were nominated under different categories. “I earn my living mostly as an oil painter, and if I can’t get in under what I do,” I told them, “I don’t want to come in through the back door.” That time I made it. I will tell you this, as I admitted to a young painter recently, I wouldn’t be elected today.

You hit a stride at some point where things started flowing a bit more.

Yes, but it was very tough work. I took on a lot of posthumous portraits. Here’s where my training as an illustrator proved invaluable. My friend, Bill Draper, on the other hand, couldn’t handle anything from a photograph. That’s to his credit. Mr. Johansen was asked to recreate Lincoln at the time of his Cooper Union Address, in 1860. This was 1960. He couldn’t do it. “If I could just see him,” he said to me. I made sketches for Johansen from a photograph. John was a hell of a lot better painter than I. But I had that training. I was able to handle subjects that a lot of artists couldn’t. I could recreate things, make things up. Imagination is something I cultivated in my illustration days. I don’t see much of that anymore. There is a desire to be “different,” but that’s not imagination. The imagination that my generation of illustrators had allowed them to conjure up images and be creative.

I am very interested in artists who leave a statement of the time they lived in.

Not just that, they had to design them.

Yes. When I was illustrating books, I had to design the pages and the covers. It was wonderful training.

I’m sure there are some stories you want to share about the more colorful subjects you’ve painted.

I’ve written a lot about that in my books. There were so many sitters who were colorful. A story can take on a lot of significance when someone famous is involved. I might tell you that a woman I was painting was very impatient. When she came in to my studio, she told me that I didn’t know anything about plants. She told me which I needed to water. Then she asked where I bought my carpet, etc. Once I tell you it was Katharine Hepburn, the story takes on a different dimension.

What do you think about today’s art world?

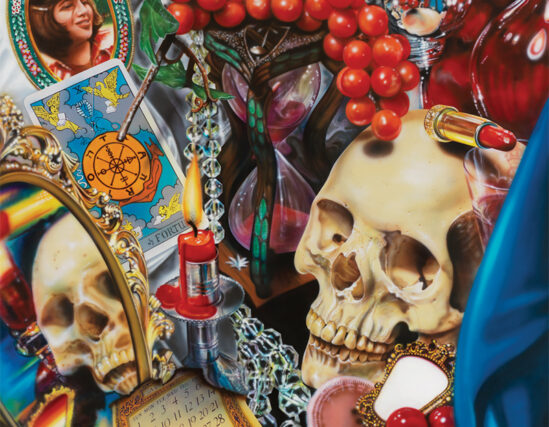

I have no expletives, nor the energy to waste. I’m disappointed. I feel it’s in many ways pathetic because so much of it consists of sound bites and a desire to be different. A shark in formaldehyde? Does that have anything to do with an appreciation of beauty or sensitivity or taste or craft? It’s just explosive, a desire to attract attention.

Sensationalistic.

Exactly. A desire to be different for difference’s sake. I know what a vagina is and a penis is. I know the four-letter words. But that’s too simplistic and easy to be art.

How does this tie in with what you said earlier about painting in one’s own time? Art too attached to the moment can be trendy rather than transcendent. When you look at a Rembrandt portrait, it’s…

Timeless. There are things that appear dated. There are things that are period pieces. You see this with the movies. Certain movies become dated, and they are not very enjoyable. And other things, because they capture the human spirit or beauty, become timeless. Salvador Dali said to me once, “Bouguereau, she is not as bad as people say. And Picasso, she was not as good.” Dali referenced Bouguereau next to Picasso in 1956.

Why do you think he did that?

Just to be different and attract attention.

I want to stay on the subject because I think it is a very important one. I’ve always thought of Michelangelo’s David as the embodiment of the Florentine Renaissance. The spirit of that time is forever captured in that sculpture. You will always derive a more profound understanding of that moment in time from looking at that piece. I think the same is true for Rembrandt, for Hals, for Titian, for Cézanne.

Look at Toulouse-Lautrec. I never talk about him and he’s one of my favorites. I remember lines that I read in a forward to Thus Spoke Zarathustra by Friedrich Nietzsche: “Every generation must have eyes for new pictures, ears for new music.” That doesn’t mean you accept everything because it’s new, and new doesn’t mean it’s good. Or valuable. And you have to keep your eyes on the past. Even my words as I say them are gone but they reflect back. I am very interested in artists who leave a statement of the time they lived in. Some painters want to paint like Rembrandt. I expressed it to one person recently: “I don’t want to hear about Sargent’s Venice, that was his Venice.” You can’t go back and repaint it and retrace him. Instead think about what Sargent would be painting, if he were alive today. What would Rembrandt be painting?

Would he be painting?

He might be Lucien Freud, curiously enough.

I want to touch upon that. There is a lot of bad stuff out there with very high price tags. We live in such a pluralistic world, because communication has, I think, created almost one culture. What they are painting in China now is Pop Art. Their art has all become “Westernized.”

Many Chinese artists are out West training to paint the West. Did you know that? They’ve got a whole crew of Chinese artists who are painting Sutter’s Gold Rush, painting the cowboy and Western scenes. What’s missing is they don’t feel it inside.

Do you think Damien Hirst’s shark or a photorealist portrait are hallmarks of the era, or do you feel, as I do, that time must pass before you can tell?

Take somebody like Andy Warhol. He shot a Polaroid photograph, projected it onto a piece of material, and then hand-colored it.

I asked my daughter Dana who’d seen a Warhol show, “What did you like about it?” She said, “Dad, do you remember, I was about six or seven years old, and you rented a house in Connecticut, and we’d go down in the cellar on a rainy day, and we’d work with magic markers. The show reminded me of it.”

Recently I visited the apartment of a banker, with connections to the New York art establishment. He dropped names like horseshoes. In his dining room there was a De Kooning. He said to me, “This is worth $12 million dollars.” I never heard him say, “I like this” or “This is what I feel about it.” His artworks were trophies, measured in dollars.

How am I supposed to react? I have a hard time trying to paint and occasionally pleased with something I’ve done. No point getting exercised. Now, I’m not stupid. In many cases, I think I’m a lot more knowledgeable and have more feeling and appreciation than ninety percent of the people who buy “art.”

A lot of academics think that I’m too far out, and not “classical” enough. I find a lot of contemporaries think I’m merely a working illustrator or commercial artist. Mere is the great word. A mere portrait painter. I’ve never looked at it from that standpoint.

Look how comics have come back. You would not believe the calls I get from people about the comic book work I did. They say, “You drew Zorro? Hawkman? The Shadow? Comics are a part of our culture.”

I believe in learning from the past, in developing your craft and experimenting. Challenging yourself creatively. The main thing is to keep working, questioning, experiencing, growing. You’ve go to train your eye and develop your emotions to work together. We are all students; there is no end to learning. As John Sloan said, “I am just a student, chewing on a bone.”

This interview was originally published in the Spring 2009 print issue of LINEA.