Supported by an abundance of caution and visitor restrictions, the Florence Griswold Museum in Old Lyme has reopened with an exhibition titled Fresh Fields: American Impressionist Landscapes from the Florence Griswold Museum. The art has been chosen from the FloGris’s permanent collection, much of which will be familiar to regular museum goers. What’s fresh are the themes, as envisioned by multiple outside curators, including independent scholar Carolyn Wakeman and ecologist Judy Preston. The show is divided into three sections: Ecology and the Local Landscape; History in the Land; and Gender and the Impressionist Landscape. The exhibition is about the region’s history, with paintings serving as points of departure.

The contrast between the beauty of the landscape and historical background is sometimes stark. A wall plaque announces, “the sense of history these artists celebrated in their works was one limited to the story of the region’s settlement by Europeans and their descendants.” A premonition of what’s to come is supplied by the notes for the exhibition’s first work, George Bruestle’s Light and Shadows, a characteristically energetic farmland vista. That farmland was created when European settlers cleared forests for their livestock, which altered glacial features and upset the habitat of wild animals. Similarly, the small milldams that Edward Rook specialized in painting impacted migratory fish. More unsettling are the notes that accompany Henry Ward Ranger’s view of Mason’s Island. Ranger, the Lyme colony’s premier exponent of Tonalism, favored sites reminiscent of the French Barbizon forest. He was drawn to an island off Noank that was named in honor of John Mason, a captain instrumental in the subjugation of the region’s Native Americans, including the slaughter of over four hundred men, women and children in the Pequot War of 1637. Other wall notes briefly mention that the halcyon scenery depicted by Lyme artists had previously been tended by African American slaves. Even the generally innocuous incursion of landscape painters had effects: a table case is devoted to artifacts unearthed on the museum’s property, including paint tubes and other toxic materials left behind a century ago. Old Lyme farmers prohibited artists from painting on their land after their cows were sickened by turpentine soaked rags that had been left behind.

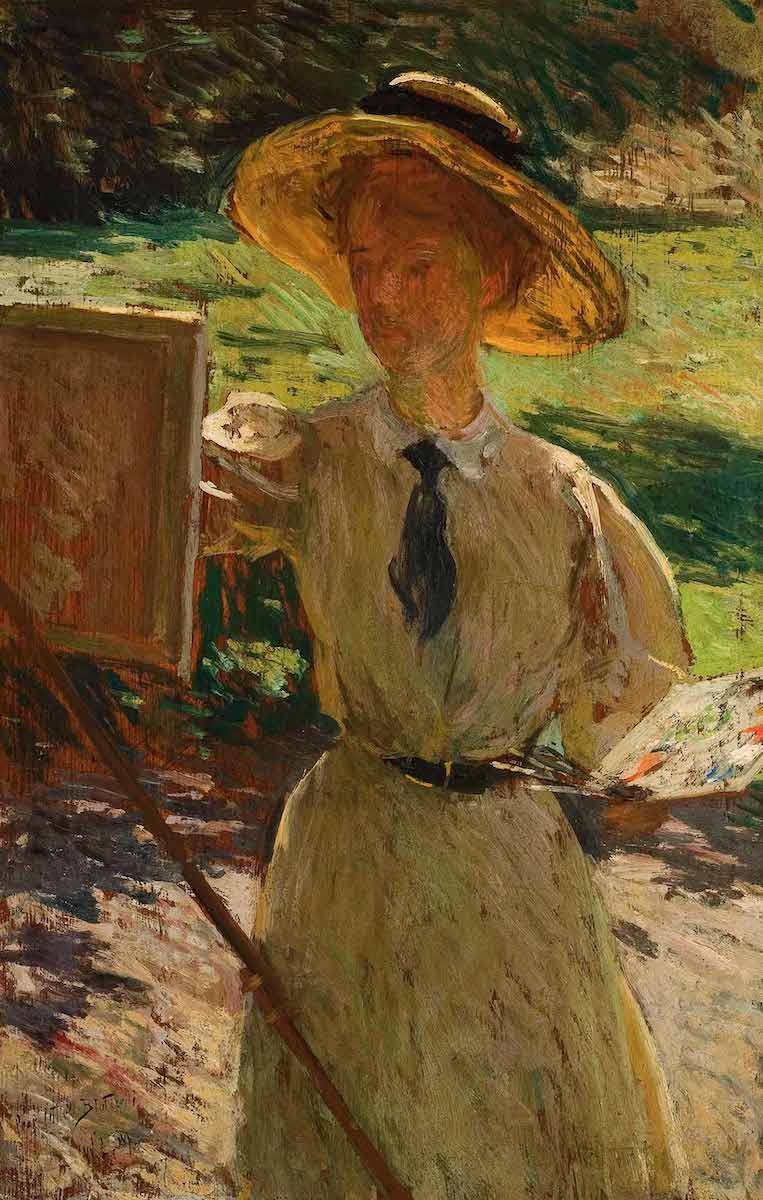

The Lyme Art Colony, once the center of the Art Students League’s summer program, was not a particularly welcoming place for female artists. Inside the Florence Griswold house adjacent to the museum is Willard Metcalf’s painting of a fifteen year old female student, which he titled Poor Little Bloticelli. In the early years of the twentieth century women were themselves divided over the right to vote. Griswold, patron to the colony and the museum’s namesake, joined the Anti-Suffrage League. Nor was Matilda Browne—whose In Voorhees’s Garden is one of the best works in the exhibition—favorably disposed toward suffrage. Katharine Ludington, a portrait painter who summered in Old Lyme, led the suffragist movement in Connecticut; her sister-in-law, Ethel Saltus Ludington, appears here as the subject of a portrait by Cecilia Beaux (Beaux was not a member of the Lyme colony).

As for the paintings, there’s a fair mix of fine and forgettable work. Among the standouts are Metcalf’s Kalmia and Childe Hassam’s The Ledges, October in Old Lyme, Connecticut, two pitch-perfect renditions of different seasons that explain the area’s enduring appeal. Other notable, if less known works include Bow Bridge, Lyme, Connecticut by Edmund Graecen; Morning at Boxwood by Mary Bradish Titcomb (signed M. B. Titcomb to avoid gender discrimination); Bank of the Lieutenant River by Breta Longacre; and the aforementioned canvases by Browne and Beaux.

I’d seen Beaux’s portrait of Ethel Saltus before it entered the museum’s collection. I know the Ludingtons, current and past. One of my favorite painting spots in Old Lyme is a few steps from the resting places of Katharine and Ethel Saltus in the Duck River Cemetery. Many of the sites identified in Fresh Fields—Lieutenant River, Smith’s Neck and Sterling City Road—are familiar to me. They remain places of natural beauty, and images of them constitute the history, and mythology, of Old Lyme.

That mythology has been the Florence Griswold Museum’s bread and butter. It is the promise of sunshine and gardens that attracts summer tour buses. But this is no ordinary summer, with visitors wearing masks and allowed in at a pre-registration trickle. Fresh Fields has a complicated agenda. It takes up the subjugation of people that created economic gentrification and the repurposing of land that produced scenic gentrification. This hewn landscape has seduced generations of artists, whose interests went beyond the mere appreciation of painterly vistas. Metcalf was an amateur naturalist, and Hassam engaged in efforts to preserve mountain laurel, whose decorative branches required legal protection from passing admirers. Many artists (the League’s Frank Vincent DuMond comes to mind) took up permanent residence in Old Lyme. Yet, little acknowledgment is accorded here to the artists’ connection to the land; Edward Volkert’s painting of farm oxen and George Newell’s Salt Haying are invoked as reminders of encroachment by British colonists.

The question that seems to be posed is whether the Lyme Art Colony’s interest in landscape, light, and color can be enjoyed at face value, or is complicit in whitewashing the area’s history. Is a painting by Ranger, Hassam or Metcalf a celebration of nature, a confirmation of white male dominion, or both? As a landscape painter, will my view of the subject change? Probably not, insofar as we frame our view of the world to suit our needs. I’ll still look for interesting compositional motifs, and be moved by the land not out of nostalgic homage to a bygone art colony, but for personal reasons. Perhaps the most obvious reason is the same for many artists; the existence of a more or less natural habitat in which to work and live. I’m grateful for the amount of land spared from development, but in today’s climate—both political and environmental—our very breath is imperiled by the same impulses that first colonized the area, except now writ large, propelled by corporate interests. If Fresh Fields tells of our less noble past, its art reminds us that what remains of nature can easily be lost in a callous future.

Fresh Fields: American Impressionist Landscapes from the Florence Griswold Museum continues through November 7, 2020. A virtual tour of the exhibition is available online.