You can leaf through an anthology of graphic art and find masters who channeled outrage or were gifted satirists, but none hit a profoundly humane note as persistently as did Käthe Kollwitz. Her peers have been few: Daumier and Goya are roughly analogous for their exposition of human nature in black and white, and there the list seems to end. Hers was a singular voice of compassion at a time and place when the human conscience had been all but snuffed out.

That time was the first half of the twentieth century, the place was Germany, and the era was memorably summoned on a recent dreary day in the third floor galleries of the Museum of Modern Art, where Käthe Kollwitz had just opened. MoMA has been slow to recognize aspects of the foundations of modern art—its show of Degas’s monotypes in 2016 was the first time the museum had honored the artist with a solo exhibition. And though Kollwitz could draw as well as any artist of her—or any—era, she has rarely received her due in this country (The 2021 closing of Galerie St. Etienne’s exhibition space on West 57th Street, and with it regular surveys of artists like Kollwitz and Schiele, left a cultural hole in midtown). Better late than never. MoMA has the muscle to gather work from all over the world, including a wealth of drawings from the artist’s native land. The curators have illuminated Kollwitz’s working process for several prints, including Woman with Dead Child and Sharpening the Scythe. The latter, part of the Peasants’ War series, was initially conceived as an image of a man instructing a woman on the use of a scythe. Eventually, Kollwitz boiled the idea down, wisely dispensed with the male character and focused on a woman, wearily hunched over her weapon. Each drawing and print is powerfully drawn, and we follow the progress of the design to its conclusion. Occasionally, Kollwitz tried and dismissed an idea, but nothing here is chaff. There are 120 drawings, prints and sculptures, and every piece feels essential.

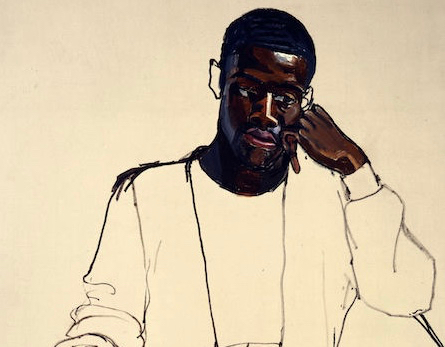

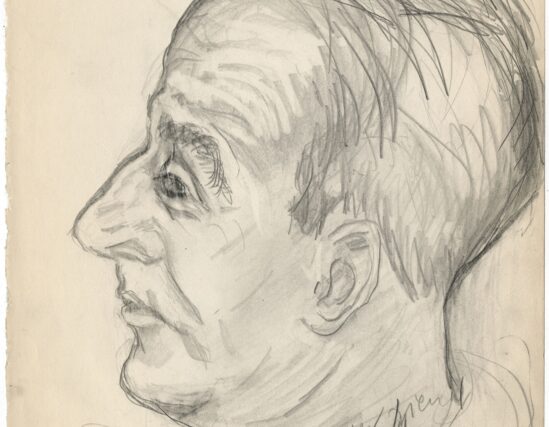

Arranged chronologically, the exhibition opens with self-portraits from the early 1890s, when Kollwitz was in her mid-twenties. Even in an era that produced technical competence as a matter of course, the drawings are remarkably accomplished. Kollwitz’s personality, her dead reckoning with herself and the world, is already fully formed. Her face is not conventionally beautiful, yet it is riveting. In Self-Portrait, Facing Half Right, the hatching with pen, fine and densely overlaid, is further enriched with brush and ink. The combination of needle-like precision and broad washes translated naturally to printmaking. There’s a tactile sensibility, beyond the mere use of light and shadow to model form. The eye sockets, nose, mouth, and transitions around the chin and nostrils are fleshy. This earthiness would inform her depictions of workers. Even in heroism, Kollwitz’s figures retain a primal peasant stature—bent, calloused, they are unromantic descendants of Millet’s and Van Gogh’s laborers. Kollwitz claimed to have taken to her subjects not from empathy, but because “middle-class life seemed pedantic” to her. Her husband, Karl, was a doctor who treated the poor of Berlin, and Käthe became a confidante to his patients. She later recalled her initial interest:

“[W]hat I would like to emphasize once more is that compassion and commiseration were at first of very little importance in attracting me to the representation of proletarian life; what mattered was simply that I found it beautiful.”

The great print cycles and related works are amply represented. The first, A Weavers’ Revolt, was inspired by a play about the Silesian uprising of 1844. The six prints, small and suffused with foreboding, depict an ultimately doomed rebellion. With their use of etching, lithography, aquatint and sandpaper, they show Kollwitz’s interest in technical experimentation. The cycle was a public success, and in 1898, Adolph Menzel nominated it for the gold medal in a Berlin art exhibition. Kaiser Wilhelm II nixed the honor, saying, “I beg you gentlemen, a medal for a woman, that would really be going too far… orders and medals of honour belong on the breasts of worthy men.” With the new century came official recognition. In the 1920s, Kollwitz became the first female member of the Prussian Academy of Arts, and was awarded a full professorship and a studio. She was subsequently made a director of graphic arts at the Berlin Academy.

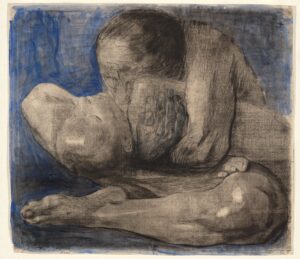

From 1902 to 1908, Kollwitz worked on the next print cycle, this time inspired by a disastrous revolution in Southern Germany in the 1520s that ended in the massacre of peasants by feudal lords. In total, Peasant War is a masterpiece. The works are larger than those of A Weaver’s Revolt, more assured in their execution (this despite the many revisions that prolonged the project), and more powerful in design and emotional impact. The highlights are Sharpening the Scythe; Raped, a woman’s lifeless figure half-hidden in an overgrown garden; Battlefield, in which a mother, lantern in hand, searches through bodies at night for that of her son; and Charge, the peasants rushing into battle, faces contorted in rage (an impression of Charge hangs over my desk, a reminder not to treat this calling frivolously). Some of Kollwitz’s most moving images were produced at the same time but not included in the Peasant War cycle: a series of Pietàs culminating in Woman with Dead Child. In 1925, Kollwitz recalled making the drawing upon which the print was based, posing with her son, Peter.

When he was seven years old and I was working on the etching Woman with Dead Child, I did a drawing of myself, holding him on my arm, in front of the mirror. That was very exhausting and I groaned. Then he said in his little child’s voice: ‘Stop groaning, mum, it is going to be very beautiful.’

These prints are both the most poignant and technically complex of Kollwitz’s works. I asked my colleague, Bill Murphy, for his thoughts on Kollwitz as a printmaker. “Her prints look like no other etchings I can think of from that time, the early twentieth century. She was able to seamlessly integrate into the prints the techniques of etching, aquatint, soft ground etching, sugar lift and drypoint, always in the service of furthering the image….I’ve never seen etchings that assimilated the charcoal drawing aura as beautifully or innovatively as hers do.”

At first blush, it’s sometimes difficult to tell the difference between the drawings and the lithographs. In contrast to the surgical precision of the early pen and brush drawings, the charcoals are economical, gestural works that suggest atmosphere, weight and movement with remarkable confidence. As a graphic depiction of the weariness of proletariat life, Home Worker, Asleep at the Table merits comparison to Daumier’s The Soup, but there are no comparable precursors, and perhaps no successors, to drawings like Love Scene I, the Berlin version of Death, Woman and Child, or Death Seizes the Children. “I have never done any work cold,” Kollwitz said. “I have always worked with my blood, so to speak.” The theme of premature mortality was likely a response to memory—Kollwitz lost several siblings in childhood—and premonitory. Her son Peter was killed in World War I, and a grandson of the same name died in battle during the Second World War.

The evolution from naturalism to expressionism is fully realized in the later print cycles. War, a set of woodcuts, was completed in 1923. In the woodcuts, grays are jettisoned and figures are presented in stark black and white. The figures are abstracted, their gestures no longer confined to individual suffering, but symbolic of an entire strata of culture, the poor and marginalized who are treated as political talking points, if they are acknowledged at all. A series of lithographs titled Death was produced the following decade. Each print depicted a different scenario, an updated version of Holbein’s Dance of Death woodcuts. But where Holbein presented death as the ultimate equalizer for all regardless of station, Kollwitz imagined an agency arbitrary and sinister, clawing its way through children or prying a mother from her child. In Call of Death, the artist is herself matter-of-factly summoned with a tap on the shoulder.

Kollwitz’s appeals for pacifism didn’t go over well with the state after the Nazis took power. In the 1930s, she was stripped of her professorship, prohibited from exhibiting, and threatened with relocation to a concentration camp. International concern protected Kollwitz from the worst fate. In later years she added sculpture to her resume, and made substantial the three-dimensional presence that her graphic art had always suggested. The exhibition’s last room includes the powerful bronze Mother with Two Children and a self-portrait head cast in copper. Yet she is more imposing, more voluminous in Self-Portrait Facing Forward (1934), a masterful demonstration of draftsmanship, calligraphic lines and broad strokes applied with the side of a charcoal stick. It is as solid as the drawing of more than forty years before, and more direct, the face indomitable, the eyes deeply set. There is no comparable series of black and white self-portraits by another artist, and few, if any, visual autobiographies of equal depth. A roll call of works missing from the current show—Self-Portrait of Left Profile, Drawing, in Washington; Cologne’s self-portrait of 1889; and the etched Self-Portrait with Hand on the Forehead—alone makes the case that Kollwitz was Rembrandt’s equal in the genre, and less vain.

One can find more terrifying images in Goya’s Disasters of War, but the intimate sorrow of Woman with Dead Child and simmering vengeance of Sharpening the Scythe are less shocking than they are uniquely affecting. They are, like the best of Kollwitz’s work, unvarnished narrative slices drawn with absolute assurance. Viewers may be torn whether to focus on the message or the methodology. Take the time to appreciate both.

Käthe Kollwitz is on view at the Museum of Modern Art through July 20, 2024.