Visiting Neue Galerie New York on a late Monday morning in March felt a bit like dropping in on a wealthy—okay, really, really wealthy—great aunt who isn’t all that excited to see you. Rooms are filled with glass display cases, and art is hung in eccentric spots, as befits a space that was originally a private residence designed in the Louis XIII style. There’s the entry line—three lines, actually: one for those who’ve pre-paid an admission fee, one for those who haven’t, and another line for those heading to the cafe. A police officer showed up briefly, though there seemed little chance things would get dicey among well-heeled museum goers. This writer extracted his phone and paid while standing in line, which enabled a move to a shorter queue. Inside, it was clear that the layout wasn’t intended to accommodate unrestricted crowds.

The current attraction is Klimt Landscapes, and after the kvetching it’s reasonable to ask whether the show is worth standing in the cold. Well, it is Klimt, so yeah. This isn’t the knockout punch landed by the Clark Art Institute in 2002. That exhibition, more ambitious in scope, first made the case for treating Klimt’s landscape paintings as seriously as his figures. And though his landscape output was limited to his summer vacations, Klimt took it seriously, too, painting all day long with an intensity that earned him the best artist’s nickname ever by the locals: Waldschrat, or forest demon. A few borrowed landscape paintings and several more from the the Neue’s collection are given context by an abundance of supporting material, drawings, photographs, jewelry, wall text and a healthy nod to Emilie Flöge, the artist’s sister-in-law and longtime companion. There’s a photo of Klimt standing at a telescope, a smoking gun for the theory that the landscapes were painted with optical aids as an explanation for their flattening of space into dense decorative patterns. It’s presumed that Klimt painted Schloss Kammer—a castle built on a small peninsula on the shore of Lake Attersee in Upper Austria—from across the lake, a distance that would have necessitated the use of a special lens. This is a more likely scenario than the previous assumption that he brought large canvases onto a rowboat and painted from the water. In the last few decades, art historians have treated the optical aid hypothesis as fact, though the logistics of keeping one’s face planted on the eyepiece of a telescope while assembling thousands of colorful brushstrokes on a three foot canvas are, at best, daunting.

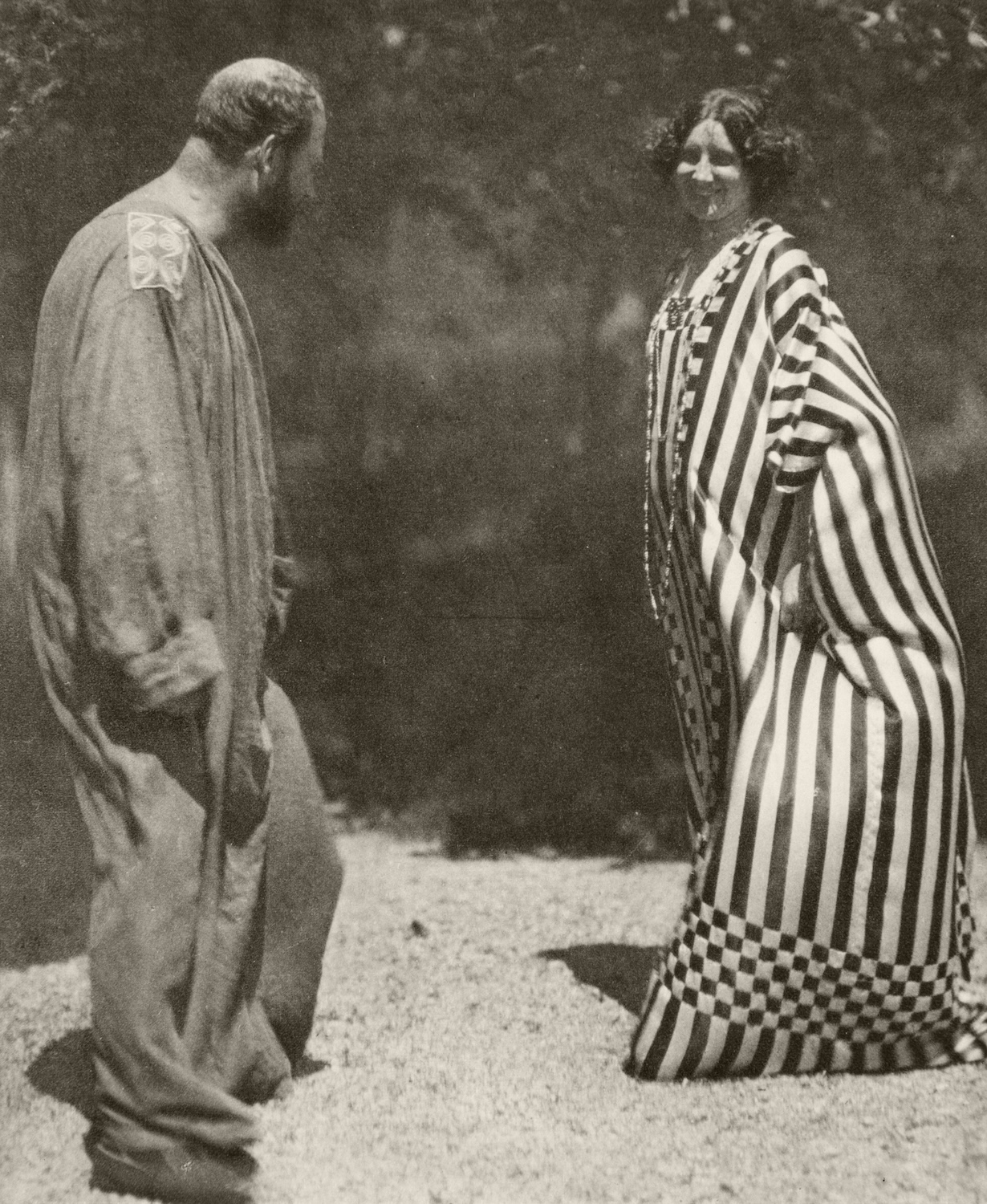

The Neue is especially well-suited to illustrate the connection between Klimt’s figure work and his landscapes. Its collection most famously includes Adele Bloch-Bauer I, the lady inundated with gold, that was purchased for a sum comparable to that of the gross national product of Tuvalu (I’m kidding—the Klimt cost much more). But it’s the later figures, bedecked with flowers and richly-colored biomorphic designs like Posthumous Portrait of Ria Munk III and The Dancer, that provide the bridge between genres. In the summer Klimt escaped Vienna and the demands of portraiture, accompanying Flöge and her family to the countryside, where he painted as he pleased. “He starts,” observes curator Janis Staggs, “to conflate his portraiture with his landscapes.” The florid summer colors appear in his figure work, perhaps in order to tie the genres together, or as a way to prolong or revisit the sensory experiences of forests and lakes. Maybe Klimt was simply looking to revitalize his portrait painting, as pastoral life had revitalized him.

Aside from genre, the most obvious difference between Klimt’s figures and landscapes is the overt geometry of the latter. An evocative design, the Neue’s haunting The Large Poplar Tree I of 1900 is still consistent with late nineteenth-century symbolism, depicting an open space, broad sky, soft focus and dramatic tonal contrasts. Shortly thereafter, the notion of depth is toyed with and finally subverted, until Klimt reduced the volumes of terrain to a series of flattened pieces comprised of a multitude of pointillist flecks. The sky disappears almost entirely from his compositions, as do, with a few exceptions, traditional methods of illusionism like linear and atmospheric perspective. Pear Tree (Pear Trees) of 1903 exemplifies the transitional moment, the canvas dominated by a wall of foliage. What’s missed is a fuller exposition of the paintings from the middle of the decade—the gardens, fruit orchards, birch and beech forests that balance delicate handling with compressed space. The paintings of the mid-aughts are gorgeous tapestries of narrow value range and scintillating color. They bear a superficial resemblance to French Post-Impressionism, but the offbeat elegance and nervous energy are unique to Klimt.

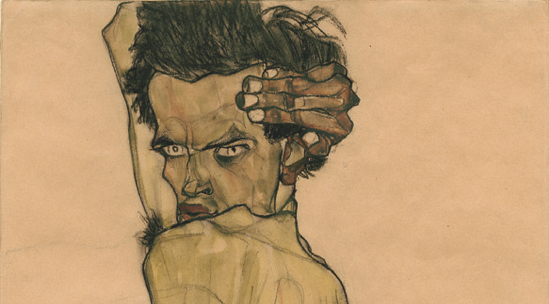

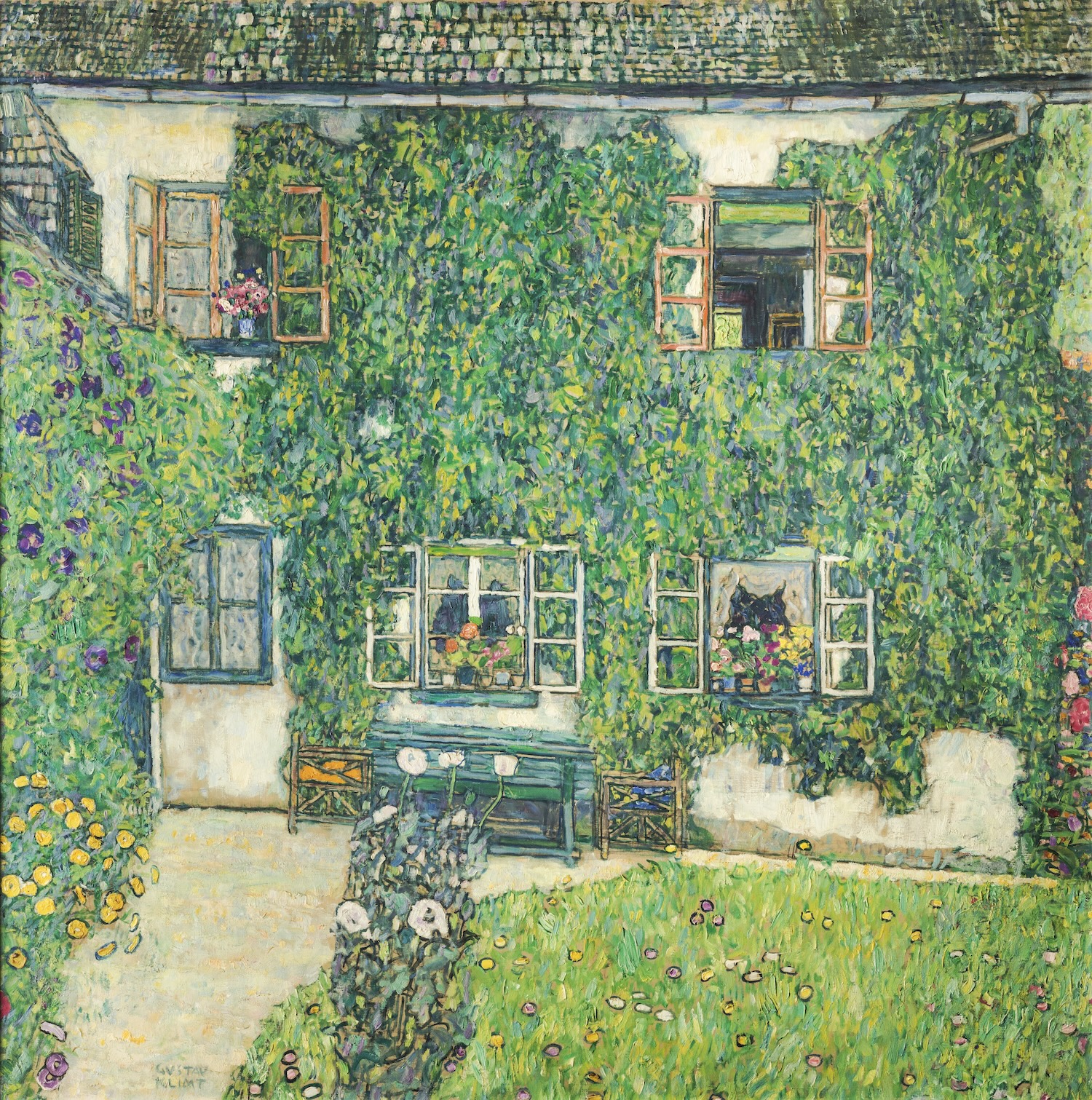

Forming the core of the show are canvases Klimt painted at Schloss Kammer. Dating from 1908 to 1914, the Schloss Kammer series is generally more thickly painted than previous landscapes, with a renewed interest in strong contrasts. Often it’s the juxtaposition of architecture and foliage that creates tension, as in Schloss Kammer on the Attersea I and Schloss Kammer on the Attersea IV. In the former, the blurred water reflections suggest a naturalistic vision, yet the designs are such sophisticated contrivances that it’s difficult to view these as plein-air paintings as we generally accept the term. By 1910, there’s a push-pull in Klimt’s work between increasingly turbulent—or at least expressive—paint application, and synthetic pictorial construction, in which architectural elements play a key role. At the same time, artists like Mondrian and Egon Schiele were making similar experiments, and one wonders about the cross-pollination between Klimt and Schiele. This is especially true of the Neue’s Forester’s House in Weissenbach on the Attersee of 1914. At the Clark show, author and curator Stephan Koja concluded that “in this case, Schiele was the model for Klimt.” It’s a powerful image, graphic, chromatic, a work of artfully channeled violence, and maybe my favorite landscape in the exhibition. Soon thereafter, Klimt’s landscapes hardened, taking a more strident direction in color, and the compositions lost some of their equipoise. We’ll never know how his work would have further developed. World War One and the Spanish Flu were ravaging Europe when Klimt suffered a stroke and died in 1918. He was fifty-five.

For the uninitiated, Klimt Landscapes is a fine introduction. Those hoping for something more will still welcome this limited snapshot of one of the early twentieth century’s great landscape painters. The peripheral pleasures of the permanent collection, including Klimt’s figures and works by Schiele and Richard Gerstl, sweeten the pot.

Klimt: Landscapes is on view at Neue Galerie New York through May 6, 2024.