Lucia Fairchild’s desire to study art was dimly received by her father, but he proposed a compromise: he would support her education if she spent her sixteenth year as a debutant. His hope, no doubt, was that an advantageous match would be struck. It was not, and Lucia was free to study, first with Dennis Miller Bunker in Boston, then with H. Siddons Mowbray and William Merritt Chase at the Art Students League of New York.

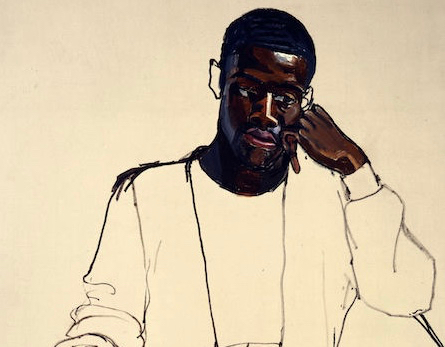

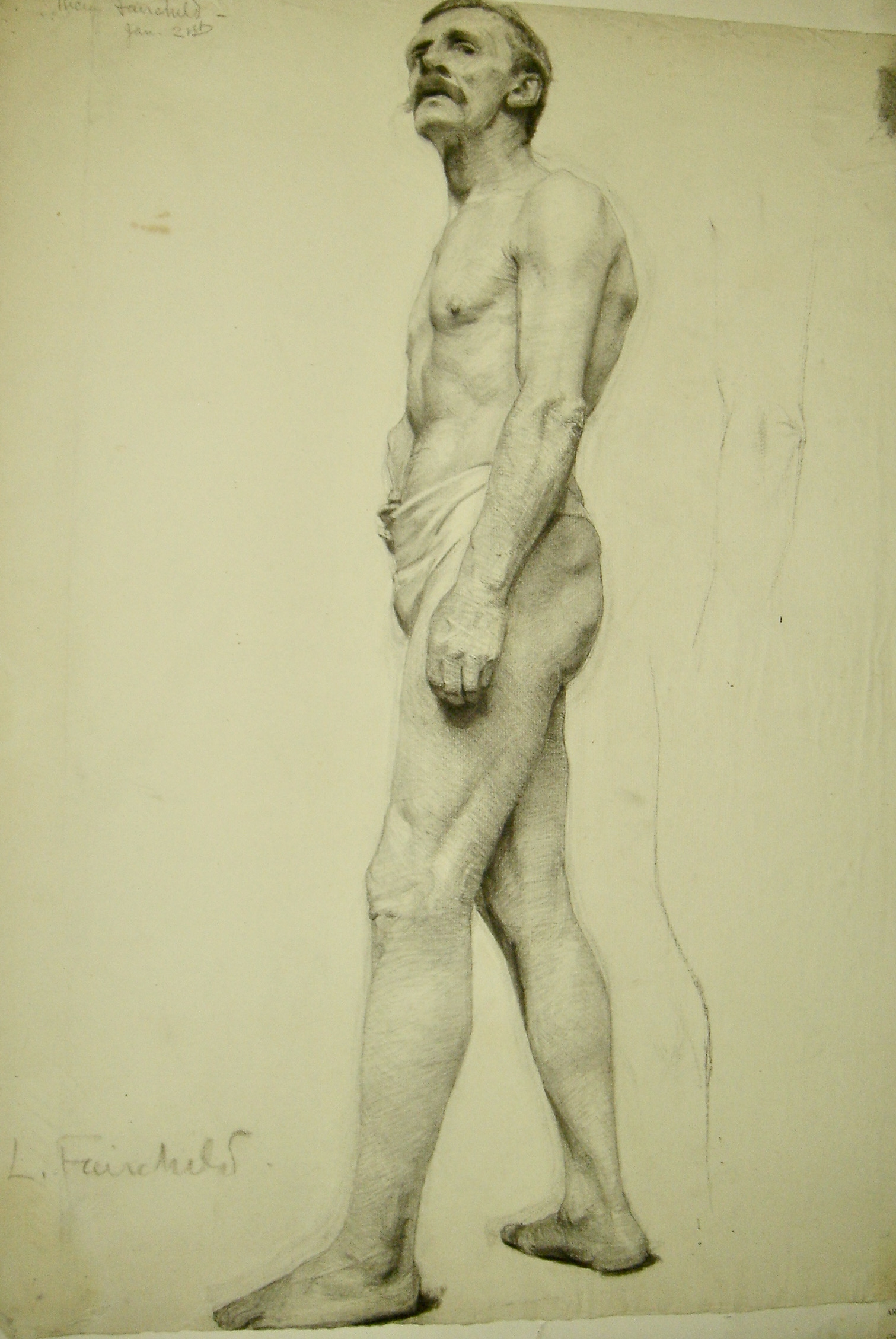

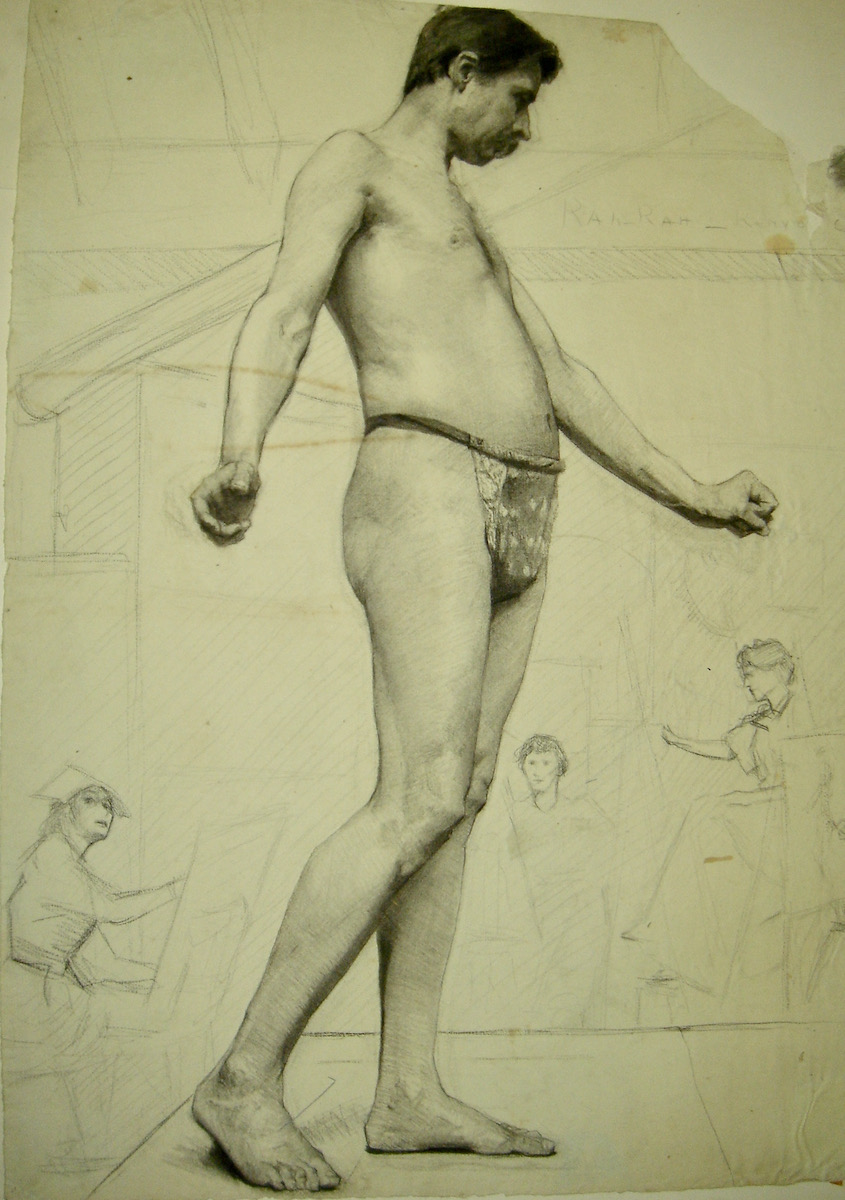

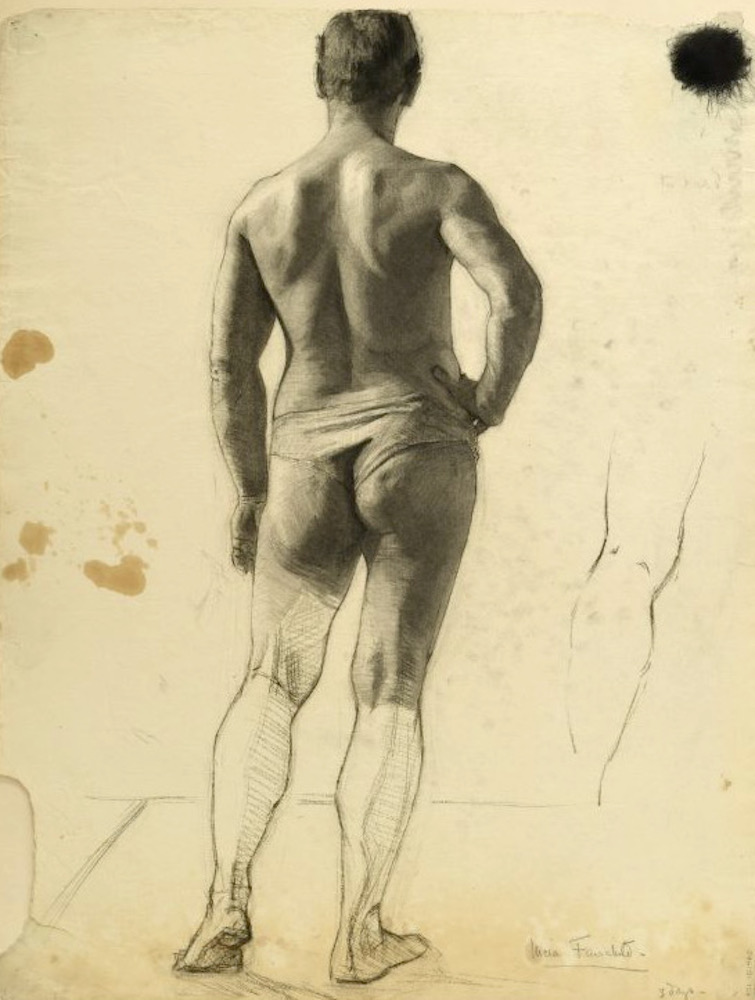

There are four drawings by Lucia in the permanent collection of the League. All are figure studies, presumably done in Mowbray’s class. They are very good examples of academic drawing of the period, with fine control of values, razor-edged contours and, but for one exception, no interest in the environment in which the models reside. Three of the figures are male, each wearing loincloths, as mandated in a women’s sketch class; a reclining female nude required no such covering. Two of the figures are seen in rather flat light and two are lit from the side, producing a fuller value range, always a plus when one is depicting sculptural form. Lucia was adept at the nuances of illusionistic rendering regardless of the angle of illumination.

Which is really quite remarkable, because Lucia Fairchild—the Fuller surname came with marriage a few years later—was only seventeen or eighteen at the time (although some sources, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, list her birth year as 1870, the family and other sources maintain the correct date is December 6, 1872). The drawings are masterful in their naturalism; the specific character of each model is observed with a keen eye, and Lucia is already knowledgeable in anatomy. Technically, she was a borderline prodigy, though her skill was employed a bit dutifully. A beautifully-modeled standing figure was left unfinished in the legs, where the linear framework and initial hatching were laid down methodically, as an exercise rather than a response to weight and tension. The most interesting of the four drawings depicts a standing male model with outstretched arms, resolved with cool accuracy, while behind him the beginnings of a studio interior includes three fellow students drawing at their easels—a document of academic study and its segregation by gender. Soon enough Lucia was on to bigger things. Barely out of art school, she was commissioned to paint a mural for the World’s Colombian Exposition in Chicago at the ripe age of twenty.

Lucia was born into a Boston family of great means and high culture. Her father was a banker and investor, her mother a poet. The Fairchilds were patrons of the arts who numbered among their friends Mark Twain, Walt Whitman, Howard Pyle and—most significantly for young Lucia—John Singer Sargent. Sargent was brought into the family’s orbit via commission; Lucia’s mother was a fan of Robert Louis Stevenson, who had been a visitor at the Fairchilds’ summer home in Newport. Sargent’s third portrait of the writer was painted expressly for Mrs. Fairchild.

During his whirlwind trips to New York and Boston to satisfy portrait commissions, Sargent stayed with the Fairchilds to relax and recreate. Yet he was always painting, and he produced a number of informal portraits of family members. Mostly he focused on Lucia’s older sister, Sally, a renowned beauty who was best friends with Sargent’s sister, Violet. Lucia followed Sargent’s movements closely, chronicling his appearance and conversations in her diary with extraordinary detail. The best source is an article published in 1986 by Lucia’s granddaughter, Lucia Miller, which features excerpts from a Boston stay in 1890, as well as meetings in Paris and England in 1891. Lucia was a sophisticated student artist in her late teens. Sargent, in his mid-thirties, was enjoying success as a portrait painter on both sides of the Atlantic.

Their conversations, at least those which Lucia recorded, ran from art to literature to gossip and love. Sargent said that his friend and patron Isabella Stewart Gardner looked like “a lemon with a slit for a mouth.” There were rough critiques of Dickens and Oscar Wilde. Sargent thought his colleagues Abbott Thayer and Thomas Dewing precious in their choice of subjects. He spoke of the difficulties dealing with headstrong clients; one elderly subject took issue with a passage of his portrait, “and with his finger rubbed it out.” In a few years, Lucia would have far more trying experiences with wealthy patrons.

In Paris, Sargent accompanied the Fairchilds to the Louvre, where he rushed from one painting to the next, pronouncing some as trash and lingering before others. When his enthusiasm was piqued by a Botticelli or an Ingres, he did something that would be unthinkable today, touching the surfaces of the paintings in admiration. They found themselves in a gallery of Ingres’s drawings, the ceiling of which had been decorated by Sargent’s teacher, Carolus-Duran (a drop ceiling covering the mural has since been installed). Sargent pointed out the parts he had helped paint. Lucia may have been smitten, but she was not intimidated. “He was looking wonderfully handsome & tanned & rather thin, with the Legion of Honor ribbon in his buttonhole.” She wrote, “He is so great,” then tried, unsuccessfully, to erase it. Talking about his sister’s impending marriage, they debated whether love was a precondition for a successful union. Lucia took the romantic tack, while Sargent held the view that passionate love would with time degrade to passionate enmity. “The chances,” he said, “seem to me much greater for happiness without all that tremendous feeling.”

On Lucia’s mind was an art student she’d met in Boston named Henry Fuller. Her father disapproved of his finances, when what Fuller truly lacked was character. They married in 1893, the same year that a stock market crash all but wiped out the Fairchild fortune. The story that followed is well told by Donna M. Lucey in Sargent’s Women. In a trice, Lucia’s life of privilege was gone, as was her hope to continue painting murals, a trade for which there was no reliable market. Fuller refused to take on commercial work, maintaining that it was beneath his dignity as a fine artist. While her husband stayed in New England, Lucia devised a strategy to support them and soon, two children as well. She moved to New York City, spearheaded a revival of miniature painting, and founded the American Society of Miniaturist Painters. Lucia settled into a dingy apartment, running around the city to paint tiny portraits with watercolor on ivory. Desperate for work, she was reduced to bargaining with millionaires over already modest fees. She sent her earnings home to Fuller, whose selfishness she romanticized as creative integrity. Lucia’s situation was complicated by chronic symptoms that left her bedridden for weeks at a time. Her family chastised her for laziness. It was years and an unnecessary surgery before what we now know as multiple sclerosis was diagnosed.

The Fullers took a home in New Hampshire and were mainstays in the Cornish Art Colony. The colony was comprised of the summer residences of notable artists; the atmosphere was idyllic and bohemian. Lucia and daughter Clara posed nude for Henry’s masterpiece, Illusions, now in the Smithsonian. Soon thereafter she became involved with Thomas Dewing while modeling for one of his best paintings, The Spinet. Lucia’s indiscretion paled compared to her husband’s serial philandering, and the couple separated after 1905. Lucia won medals at major exhibitions, the Metropolitan Museum of Art purchased a painting in 1915, and she taught briefly at the League. Eventually the sclerosis disabled her and robbed her eyesight. Lucia died of pneumonia in 1924, at age fifty-one. The Fairchilds’s fall from grace was absolute. Sargent’s portrait of Stevenson was sold to pay expenses. At least three of Lucia’s five brothers, handsome Harvard graduates, took their own lives. In a single generation one of the most prominent and enviable families in Boston had descended into ignominy.

This history adds layers of meaning to the League’s collection of drawings by Lucia Fairchild Fuller. They are, for starters, the work of a precocious and ambitious young woman, barely more than a girl when she drew them. Dispassionate in their technical accomplishment, they hide the artist’s true nature: Lucia had tremendous feeling for her work and her family, and it’s impossible to read about her without losing a little of one’s heart on her behalf. As she sat drawing in class, she must have been flush with the good fortune of her talent, her friendship with Sargent, and all the promise her future held.