Ira Goldberg: You are originally from Garrett Park, Maryland. What made you decide to go to the Art Students League?

RM: At that moment, in the 1950s, young people went to New York if they had aspirations in some area, particularly painting. They thought, “New York is the place.” It turns out to have been. It still is.

IG: At that time, the art scene, especially in New York, was dominated by abstraction.

RM: It was, but a few feisty individuals went in a different direction.

IG: I guess you were one of the feisty ones.

RM: Well, I couldn’t take it. I’d make my position more glamorous by saying I objected to it. I didn’t object to it; I couldn’t do it.

IG: Did you try?

RM: I did, but probably only half-heartedly. I had a number of very popular models in my memory.

IG: Who were those?

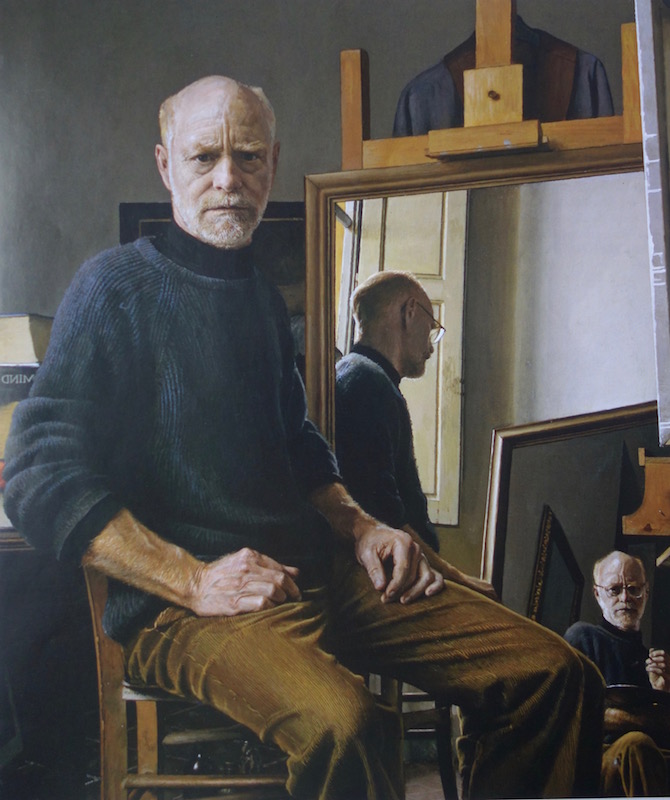

RM: The most modern of them was Degas. Degas for me was the sun. Looking further back, there was the wonderful drawing of the Italian Renaissance. Then, the person who has been probably my greatest hero all my life is Rembrandt.

IG: Well, he is the universal hero. I think he can be a hero to any type of painter. He covers all the territory.

RM: But to me particularly, it is the human thing.

IG: Degas to me is also someone to be highly revered. I admired how he really delved into color with his pastels.

RM: Actually, I have an aversion to pastels. I have always loved him as a draftsman. Degas thought of himself as a draftsman. He loved to draw.

IG: Don’t we all. Although some painters draw with the brush.

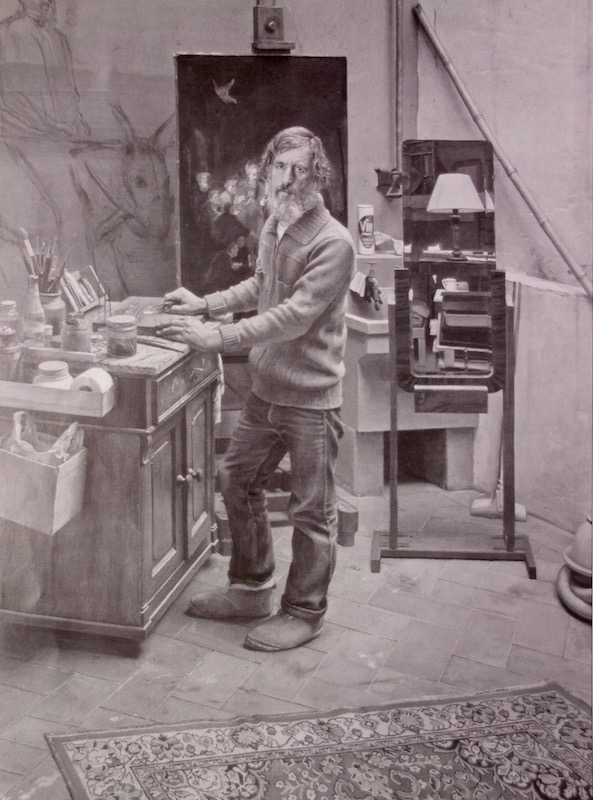

RM: Or draw mostly in preparation for a painting. I do a lot of that. But I do very little drawing, much less than I ought to.

IG: Do you draw on the canvas before putting down pigment?

RM: No. I draw on paper, and then I transfer the drawing because I can rough things out and erase. I don’t want to mess up the canvas. But then I mess it up anyway. I put in a rough beginning, and then I have to refine it … infinitely. [Laughs]

IG: I notice there is a good amount of texture on your painting surfaces.

RM: Yes. [Laughs]

IG: Do you think of it as a mess?

RM: Well, I don’t really want it there, but I don’t take it out except where it is really obstructive.

IG: I would expect that, in most cases, the surfaces of work by painters who do the type of work you do are often exceedingly smooth and so controlled. There is something quite refreshing about it. Thinking of Rembrandt, here you really do see texture and the corrections made. And to me that adds to the work.

RM: Well, it shows the battle, doesn’t it?

IG: Why hide that?

RM: Well, I excuse myself saying that. Something that is widely done, that aids in creating those slick surfaces is to take a photograph or several photographs of the subject and then project the various bits onto canvas and then just paint it.

IG: What’s the fun of that? [Both laugh] You don’t do that. You just work from drawings.

RM: From life.

IG: From life, and working with the drawings. I don’t particularly care about how an artist arrived as what she arrived at, if what she arrived at is …

RM: Beautiful.

IG: Yes.

RM: Yes. [Both laugh] I put that work in intentionally because it seems to me absolutely essential.

IG: If you can convey beauty by whatever means you have, then do it. I don’t think it is going to take away from the art. Getting back to your time at the Art Students League, I see you studied only with Robert Brackman.

RM: I studied with Brackman and poked my head into a few other classes.

IG: But you didn’t stay all that long. About six months.

RM: Well, he tried to get rid of me.

IG: Why?

RM: Well, he patted me on the back one day. He was a little fella, rotund, and affectionate, and he was adored by the ladies in his class. He told me, “There is nothing I want to help you with. I think you should just run along.” But he wasn’t trying to dismiss me. He just said, “I can’t do anything here.” Brackman wasn’t looking for the same thing in art that I eventually began to look for.

IG: What were you looking for?

RM: Brackman kept talking about color. And color seemed to have a very powerful influence on him. He exaggerated color in his work. He claimed, “A painter exaggerates what he sees.” In a certain sense that is absolutely true. Perhaps it isn’t intentional but happens as a result of the feelings by which one paints. Inspiration drives you to do it.

IG: That seems to be evident in your work.

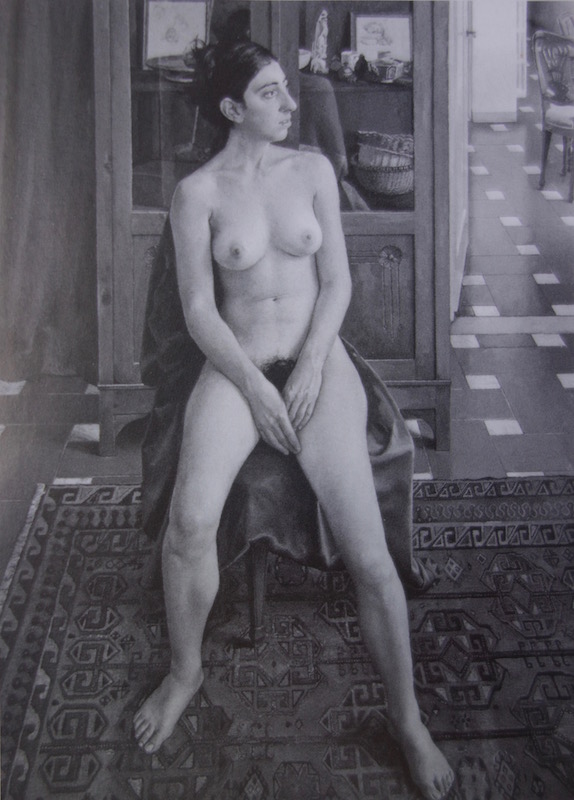

RM: A beautiful naked woman is a beautiful naked woman. That Kleenex over on the counter, you see, isn’t so interesting. [Laughs]

IG: So, you were really always interested in the figure, which is apparent in your current exhibition.

RM: Yes, I always was, but I was ashamed of it because we were taught to be during the fifties and sixties. There were objections: “You’re still doing this? What are you doing this for?”

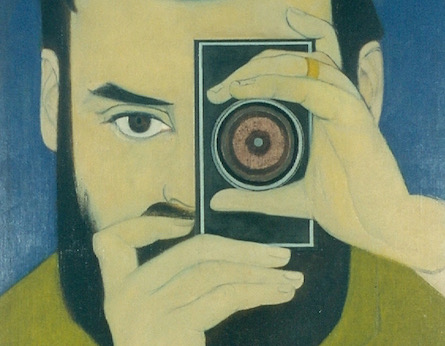

I think about whether highly realistic painting, the kind I do, is really necessary anymore. We’ve got the photograph. We don’t need painting. But, then again, the point of a photograph is to record something. It is not, like a painting, an internal thing.

IG: As I see it, the photograph is the standard for so much realist art today. Rather than working from life—a means that can yield an artist’s vision—artists opt to work from photographs, which yields, as you say, a record lacking personality. The two are very different.

Inventing something is not only uninteresting to me, I can’t do it and never could. Looking for a source, looking for something, this has been my path.

RM: They are. The photograph always betrays itself: If a person tries to hide that he is working from a photograph, he never succeeds. He always makes some error.

The telltale sign is too perfect a job on the folds in the cloth, for example, or too exact a rendering of a person. Why? Because an artist doesn’t have the time to do that working from life, as we would from a photograph.

IG: So, once Brackman delivered the message that he really wasn’t the guy for you …

RM: What he meant was, “Run along and be a painter.” I took it as a compliment.

IG: You had training before that, I assume.

RM: No. I did spend some time at the Corcoran School. But mainly I puttered around. And from birth practically, I was drawing.

IG: It sounds like you had from the beginning a very strong idea about being an artist, and you pursued it without wavering.

RM: To be honest, I was influenced by my times. I would sit down, for instance, when everybody believed in abstraction, and try to abstract things, but it didn’t give me any satisfaction. Inventing something is not only uninteresting to me, I can’t do it and never could. Looking for a source, looking for something, this has been my path. First, the thing has to convince me. Once it convinces me, I go after it.

IG: So what happened after you left the league?

RM: I shared an apartment with an old painter friend. We’d met in Maryland when we were twelve, and we’ve been friends ever since. We shared an apartment for a while, and then he went to Korea and I stayed. Then I lived with another artist, also a student of Brackman (who is still a very good friend) over on the West Side, 76th Street, between West End Avenue and Riverside Drive. It’s a lovely part of the city because there were (and still are) a lot of intelligent people there. In fact, right close to us, was Raphael Soyer. He was living down there on the park.

IG: Did you know him?

RM: Yes, but not then. I first met him in Italy. He was friends with a friend of mine, Sidney Alexander. And right away I got a straight-up from Soyer. It was very touching in a human short of way. I mean his vigorous rejection of me.

IG: Really?

RM: I was competition coming up. [Laughs]

IG: But so much younger.

RM: Oh yeah, and in me he had nothing to worry about.

IG: He had just a totally different approach to work.

RM: He was a little bitty man, like his twin brother. And very sharp. Much later I came across him in New York and accosted him. [Laughs] He invited me up to his studio and showed me his stuff.

IG: Let’s go back to the time after you left the league and were still living on West 76th Street with your friend.

RM: Yes. We were painting. He would paint all day, while I worked a job. So, I painted at other times. It was a really difficult period. All along I’ve always had to maintain myself during that time by working menial jobs.

IG: Of course, but you still found time to paint. I guess there weren’t many places in New York to show the type of work you were doing.

RM: I got a rejection every time. I decided the leave the United States then. It was 1959.

IG: So you didn’t even last a year in the city after you left the league, in February of that year.

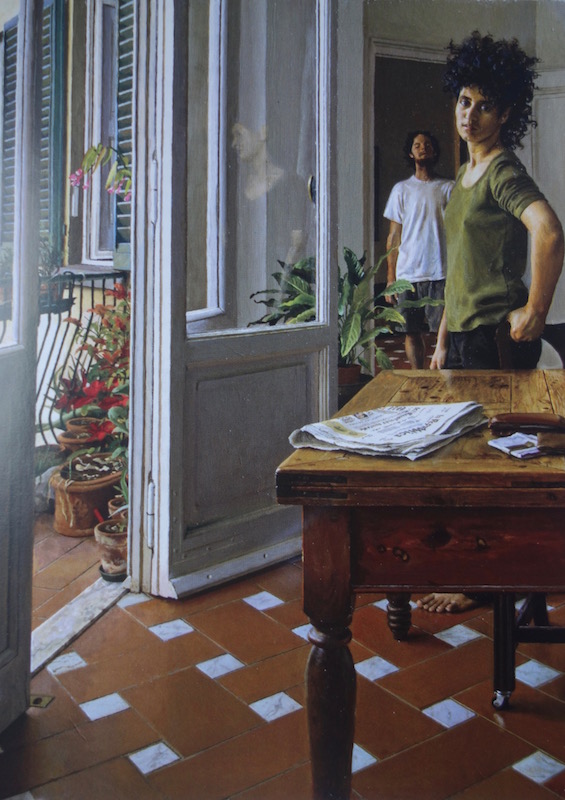

RM: We, my roommate and I, just bounced around. Then I decided. No, I’m going someplace else. And I went to Italy.

IG: You could live in Italy cheaply then. It must have been so fabulous to contemplate.

The camera doesn’t notice particulars. The camera takes the whole business and indiscriminately records it in an instant. But it is a tensile mind, not a camera, that’s capable of noticing the exact shape of a flower’s anatomy to note its significance. The relevant qualities of the thing are noticed.

RM: It was. It was also less crowded with Americans. I was a definite foreigner then. Nobody was trying to embrace America over there. I’m sure some people were, but not to the extent that they do now. The American is really regarded as a polluting influence. And it has been that way for some years.

IG: You didn’t have to save up a whole lot of money in order to do it.

RM: Well, I got a job right away. My wife (whom I met in Italy on my third day there) and I took jobs copying decorative things onto silk-screened panels. We worked at that for several months, until my wife got too pregnant to continue. That earned us some money. And as you say, it was very inexpensive to live there. My wife was marvelously inventive about food, so we lived well and cheaply. My wife, Anne Eldridge Maury, is a botanical illustrator, the most famous one in Italy.

IG: So where in Italy did you settle?

RM: Florence.

IG: I traveled there recently after a long absence. I experience this incredible re-enchantment with the city. I came away feeling that every artist should have the opportunity to visit. The wealth of art that lives there is incredible. And the atmosphere is just so conducive to creating. You can take it with you wherever you go. Once you’ve been touched by it, it becomes part of you.

So we’re in Florence, and it’s 1960, and you’re working for this lithography/silk-screen firm.

RM: Well, I didn’t do the silk-screening. They had a man who did that. My wife, Anne, and I would color them. After which, Anne, while she sat waiting for the baby, continued to work, and I was painting. I have never really not painted. I’ve always painted.

IG: That’s wonderful.

RM: And the guys around there began to warm up to my stuff. They said it wasn’t art obviously. It was painting out in the country, that kind of thing, which is semi-realistic. That was all right. Nobody was rich, and they didn’t have a lot of money. So, you’d get a couple of weeks of life out of them. Well, that’s a couple of weeks of life. And we kept hedging along like that.

IG: So you got to sell them.

RM: Locally.

IG: Was there any art scene in Florence at that time?

RM: Well, a lot of nice guys who were communists tried to help me and encourage me and keep me. We went to shows all over the place. And I participated. But really what one was trying to do was peddle a painting here and there, just to keep eating. But hey, what’s better than that? I exchanged a week of meals for a painting.

Eventually I started selling in the United States. I came to Washington, DC, in 1981, to help my mother while she was dying. I took photographs of paintings around to galleries, out of which I was thrown. But at a certain point somebody became interested. In one gallery, a girl look through them, and called “Jem” into the other room. She took him the photographs, and after a few minutes, out comes a little Chinese guy who said, “We can do something together.” That was the beginning. It turned out he was very good at peddling them, but I couldn’t get the money. [Laughs] And that began to be very nerve-wracking. At the same time, a couple of other people kind of nosed around. While in Washington, a secretary from Wunderlich Gallery saw my paintings, and she told Gerry, its director, to get in touch. And he did. He didn’t do it in any illegal way. He wasn’t taking a painter away, but he was saying, you know, it might be possible for you to make much more money out of these paintings, and also actually get the money. That is all he said. When things came to a head with Jem, I went to Gerry. From there it’s gotten better and better.

IG: Gerry is?

RM: Gerry Wunderlich had the gallery. He was the last of the Wunderlich family who had run the gallery for a hundred and some years. When he was forced to close, he suggested that I talk with Bob Fishko, the director of Forum Gallery.

IG: How long have you been with Forum Gallery?

RM: It seems to me since 1998. We’ve done a couple of things. This is my second show here, the other one was in 2001.

IG: So what’s life like now? You’ve established a major reputation.

RM: Well, I’m currently known in New York among those who take an interest in realistic painting. So that is much better than it ever was.

IG: What is your feeling about the overall state of the art world these days? Florence is this wonderful and, in a way, isolated place.

RM: Completely isolated. Fairyland. [Laughs]

IG: What is your sense of … I mean you kind of live in this wonderful, protective environment.

RM: Fairyland. [Laughs]

IG: You don’t have to really deal with insanity, which is so much a part of the art scene today. Do you have any feelings about it, or do you just feel removed enough from it so that it’s not an issue.

RM: There is a young, dedicated body of people doing something that I can’t see myself doing. But this is probably just my being a grandfather, an old man. I see all these kids coming from America to study at one or more of the several very good realist art schools, which now exist in Florence. When I came, these schools didn’t exist.

IG: Studio Art Centers International (SACI)?

RM: SACI. He’s not trying very much to create a band of realistic painters. I don’t think, is he?

IG: No. They basically work in tandem with art colleges in the United States who then send their students over there for a semester, a study abroad type of program.

RM: Syracuse, and places like that?

IG: Yes. The Columbus College of Art and Design. I think they also have a relationship with the Maryland Institute.

RM: That Art Institute?

IG: Yes, MICA it’s called: Maryland Institute College of Art. And others like them who just send their students over. They are very much influenced by the computer, you know, the technological … I see great difficulty in their really devoting themselves purely to the means of traditional art-making.

RM: Well, you asked me what I think about the future of art. I’ve been telling people something that, when they first hear it, they kind of scream. But it really is my feeling. That is, painting—I’m talking about Monet, or Degas, or Rembrandt—is dead. It’s become a historical thing. It is living in the past where it belongs. But I don’t give a shit. I love doing this kind of painting. And I probably couldn’t do anything, with any other assortment of media that is out there. Computers and so forth.

IG: Richard, you don’t really think that you are the only person who feels that way, do you? Paint manufacturers still make and sell paint.

RM: I think all the materials these days are being made for amateurs. Remember that you used to be able to get colors, real pigment. People knew how to grind colors. People still know how to grind colors.

IG: Nowadays, they make them so refined to begin with. You can go over to Kremer on Elizabeth Street and get beautifully refined pigment and basically just thrown in some medium and pick it up. You don’t really have to go through this whole grinding process anymore.

It is an important point that you are making. We’re human beings who make visual statements. This was probably the first thing that mankind did to distinguish himself from other animals. Sometime in the 1980s, the Museum of Natural History organized an exhibition on prehistoric art going back to 15,000 BC. I recall seeing some of the most amazing relief sculpture on small stones. The line was so delicate, so sensitive. Picasso would’ve envied it. What this show revealed to me was that it’s all been done before. You see these things that are so very old but appear as fresh, things people would be working from as an ideal in the classes at the league today. Why are we making such a fuss? Or why do we say it’s dead? They might have said it is dead 2,000 years ago, but it still continues. The need, the satisfaction one gets from being able to wield the brush will continue indefinitely.

RM: Sure that persists. But what doesn’t is the consumer for it. And that’s what I am thinking. Without a consumer, any producer dies. His spirit is still there. He still wants to do it, yet he’s doing it because he wants to do it, not because there is a need for it.

IG: So what are places like the league doing? We don’t prepare people for careers today. Only for a short time, after the Second World War, did a commercial course of study (illustration, fashion design, calligraphy) become part of the school’s mandate. And this was done to attract students funded by the GI Bill of Rights. These fields are now the domain of the computer. The league continues largely to cater to the essential, very human need for self-expression. That is why our registration is as high as ever.

RM: Still there is at the problem of the art object. Do people still feel the need to own, to have present in one’s life, an artifact a painting, made by somebody else? I think this need has definitely dropped out.

IG: Do you come to that belief because it is something you do, and do so well, by yourself?

RM: No. I would very much like to have a nice collection of paintings. But I don’t really think they need for paintings is a strong as it once was. Of course, America is one thing …

IG: Well, that and there is too much of it, too. I look at art as being this vast vat into which everything from Titian and Rembrandt to Jeff Koons is thrown in. After a while, it become a diluted soup. That is a huge problem. The perception of art today has been very much affected by that. There is very little we can actually do about it. The moment you try to create some sort of standard, there are objections. First, there is too much variation in art, but there is also so much good variation within it. I have a great deal of respect for De Kooning and what he did, and I think he pushed the envelope much further and deserves a place in history. There are those who I think tried to exploit that and never really understood what he understood and then made a mess. This is why you’ve got everything today being called art; it is as much about context as picture-making. You see, I think picture-making is something people have forgotten because they are much more involved with talking about the psychological.

RM: It’s talking.

IG: It’s become verbal, with an element of the theatrical mixed in with it. To find purely visual art in the contemporary scene is a rarity. But I understand why; to break through the information saturation brought to us by television is, for artists, a difficult task. Plus, the photograph—not painting—has become the standard currency to record and interpret events.

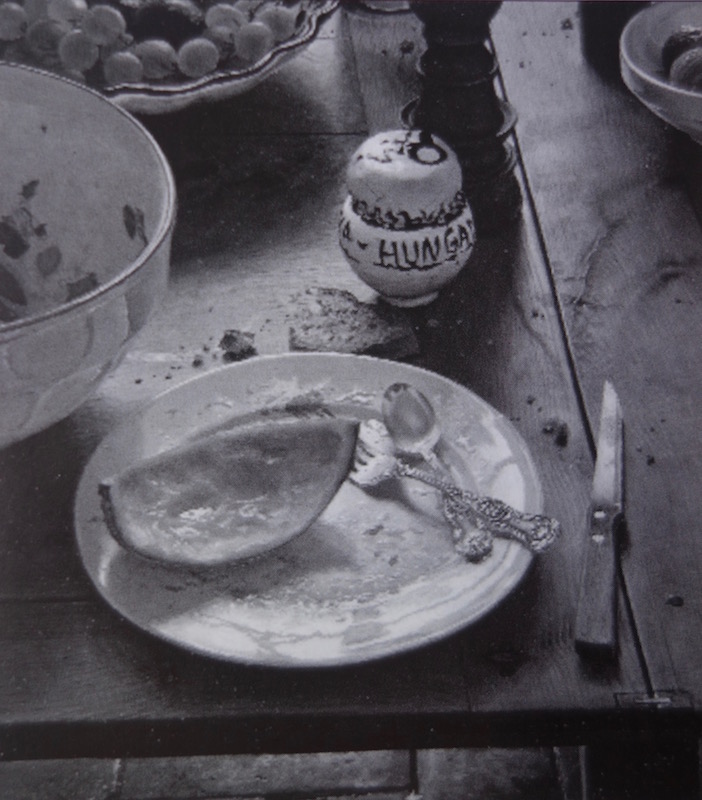

RM: The camera, though, has its limitations, I think, and my wife can surely attest to this. As a botanical illustrator, she does fieldwork to obtain visual data, the kind cameras aren’t capable of recording accurately. Anne will travel to any part of Italy, all the way up to the Austrian border if necessary. She did a book on all the wild spontaneous orchids of Italy. For this she traveled all over the place, sometimes even working in the field. Was this necessary when she could’ve used the camera? Yes. The camera doesn’t notice particulars. The camera takes the whole business and indiscriminately records it in an instant. But it is a tensile mind, not a camera, that’s capable of noticing the exact shape of a flower’s anatomy to note its significance. The relevant qualities of the thing are noticed.

IG: I recall one salient instance of that a few years ago at the Metropolitan’s Chardin show. There was one particular painting—a still life of plums on a table in a room with a window in the background. While all the paintings in the show were gorgeous, this one in particular, perhaps because it was an interior, suddenly got me; what I saw was something with more veracity than a photograph. That was a real revelation. This transcended the photograph. All of the sudden I’m in a room in the eighteenth century with these plums. It just made me so aware of the power of art.

RM: The camera doesn’t have any discretion; it only take what is presented with from precisely that angle.

IG: And it can’t experience its subject.

RM: I’ve heard so many times that people prefer a photograph to a painting—the thing that tells them more—because they don’t even realize that a painting can express more. The photographic image expresses its own vividness, something entirely different from the slightly idealized but intensely viewed scene crated by the artist’s mind and hand.

IG: You were talking before about these new art academies that you feel are not working for the students.

RM: I really think that I have not said what I wished to say at all. The new academies impart, I think, a very large practical understanding of the methods whereby visual art can be made. And their being located in Florence, where visual art abounds, can only vastly enrich this experience! I myself have had absolutely no teaching experience, but I think that the teaching done in these Florentine schools is at a very high level.

IG: But I have found that when you have these academies and these schools that have one very specific philosophy of art-making, it tends to get warped.

RM: I think so.

IG: And one of the great things about the league is …

RM: That it’s diversified.

IG: It’s diversified. Now, we are not teaching computers; we’re not teaching photography. We do have photo-etching, but that is the extent of it. No videography or anything like that. We do have an upstate campus, the stately Victorian home of former instructor Vaclav Vytlacil. It is where we introduce classes in experimental media, new offerings, if you will. We built a bronze foundry up there. We’re teaching metal forging and ceramics.

RM: Wow. People working with iron?

IG: Yes. It’s a matter of balance with a loose structure. Schools of thought tend to become rigid. We’re not living in the Venetian or Florentine Renaissance. There is a wider world.

The league is one environment where an artist not only teaches, he crates disciples, who, even if they do not work in the same mode, will carry on.

RM: Some of the genes that you’ve imparted.

IG: Exactly. Our reputation may have faded a little bit as all these great university programs have come to the fore, but I’ve always felt that you cannot teach art the same way you teach other subject matter.

RM: It’s a craft. It is the way a goldsmith worked with his students, his helpers.

IG: You’ve got to have a special relationship, an apprenticeship really, in order to understand it.

Ira Goldberg spoke with painter Richard Maury at Forum Gallery the afternoon of the opening for his solo exhibition there, which ran from October 26 to December 9, 2006. This interview appeared in the Summer 2007 print issue of LINEA.