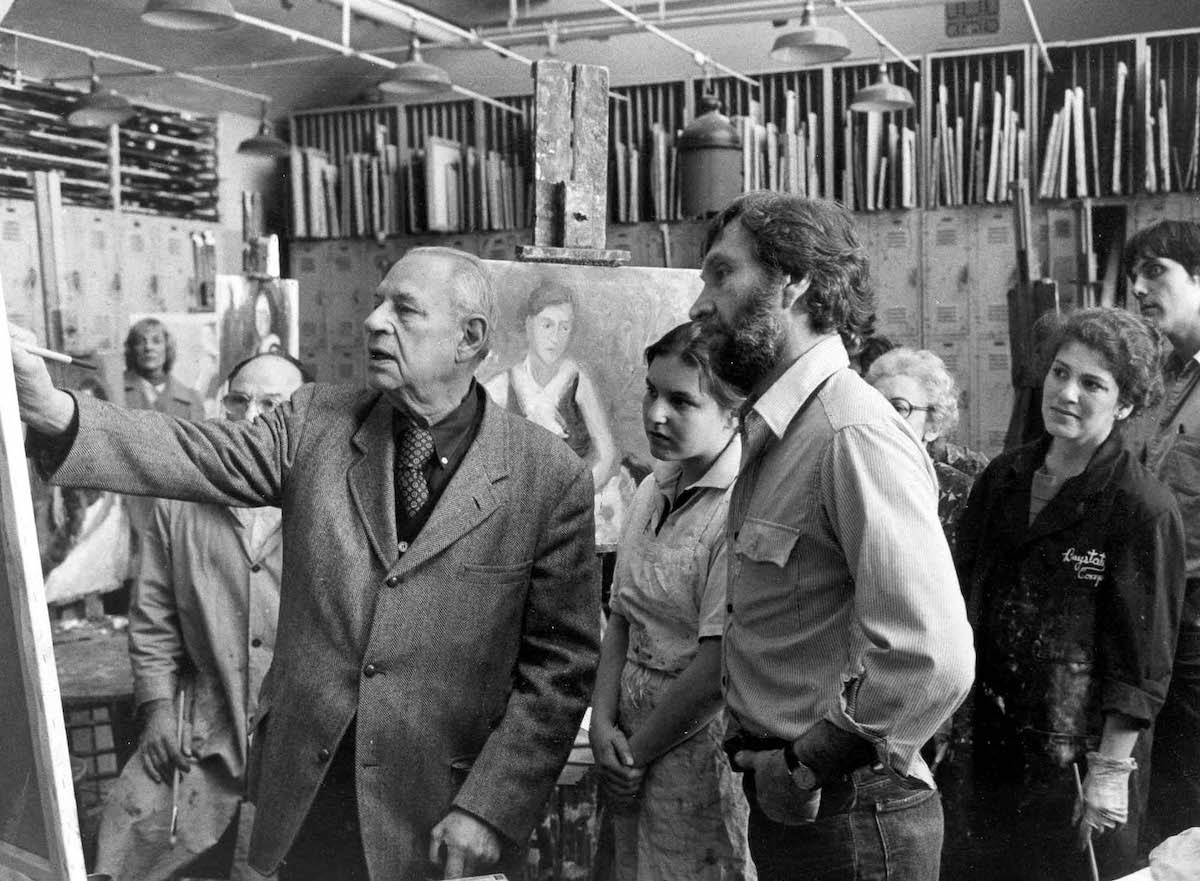

Beginning in the late 1940s, Robert Philipp taught at the Art Students League of New York for thirty-three years. I studied with Philipp at the very end, for a month in 1980. The high point of his popular reputation occurred much earlier. Henry McBride, the dean of New York art critics during the 1930s, called Philipp one of the best American painters of his generation. The assessment is striking not only because Philipp is now largely omitted from anthologies of American art, but because McBride championed modern movements in art, and Philipp was essentially a conservative. He was—and this may be a defining characteristic of many League instructors—an iconoclastic traditionalist, well enough versed in the conventions of art to take them as a point of departure.

This, from a profile in Esquire magazine in 1939:

Philipp declares that he does not work according to any formula, that the painting of every picture is an adventure without relation to the adventure that preceded it. Although he does not scorn representation, his painting is always creative; he does not always, for example, paint landscapes directly from Nature. Even in figure painting he sometimes does his best work after the model has left. He does not reject portrait commissions, but he paints portraits without compromise. He likes to change the mood and tempo of his paintings.

Moses Solomon Philipp, better known as Robert Philipp, was born in 1895 in New York City. His father was German, his mother, Hungarian. It was a creative family given to transatlantic travel. Philipp’s father painted, and he partnered with his brother, an entrepreneur of opera productions. As a young man, Philipp was a good enough singer that he briefly performed as a tenor. His studies in art began at the age of fourteen, with enrollment in League classes. Seventy years later he reminisced about the experience; Thor Wickstrom, whom I met in Philipp’s class in 1980, remembers that “He liked to tell how he went to the life class and had never seen a nude woman. The only spot was right in front of the model stand. He said all he could do was stare, jaw hanging as if before a goddess. He had to leave the room, and gather his courage to go back in.” Philipp was not long wanting for confidence. Raphael Soyer, a fellow student, wrote many years later,“He was so sure of himself—a tall, handsome fellow who was very conscious of his worth.”

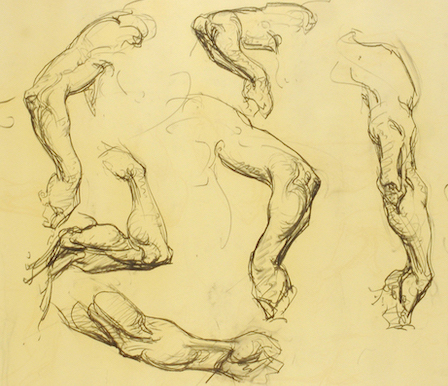

At the League, Philipp studied under George Bridgman and Frank Vincent DuMond, and later took classes at the National Academy of Design. After World War I, he moved to Paris, where he lived through the 1920s. He studied at the Académie Julian, while also absorbing Impressionism as a leavening agent to his academic studies. Degas and Renoir joined Velázquez, Vermeer, and Sargent as influences. My Mother, an unsentimental portrait that suggests an affinity with Vuillard’s Parisian portraits from the 1920s, dates from this period. For its powerful value and architectural structure, it represents a summation of Philipp’s early period. Philipp enjoyed great success when he returned to the United States, exhibiting to critical acclaim and selling paintings to private collectors and museums. In 1933, McBride wrote “He has a keen eye for character and does not fail to build up his composition with due regard to their effect as a whole. His figures have weight and belong to their surroundings unmistakably.”

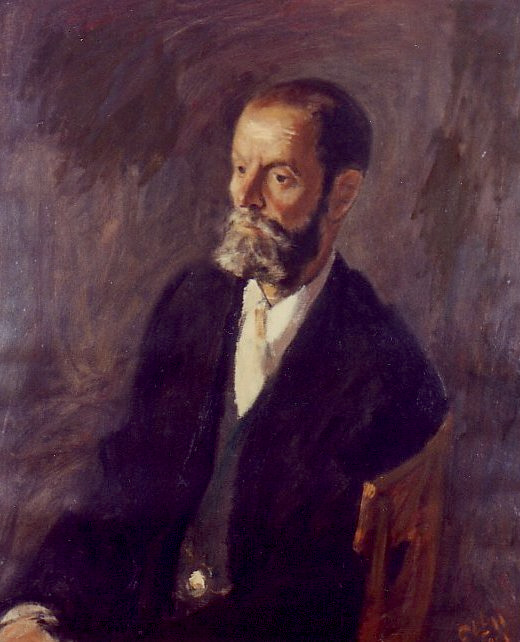

Soon after the deaths of his mother and uncle in the mid-1930s, Philipp briefly explored themes of mortality and social realism. Critics noted the darkening of his palette and a move toward earth colors, a temporary change of direction. A good portion of the later work projects a sort of Parisian fantasy in which young women share lunch in sidewalk cafes, perhaps an extended reverie based on memories from the 1920s. At the same time he was turning out retro-French cafe scenes, Philipp was still painting portraits with a clear eye. The League’s collection is weighted toward portraits of his male colleagues, among them Edwin Dickinson, Sidney Dickinson (no relation), and Robert Brackman. They’re good paintings and valuable documents.

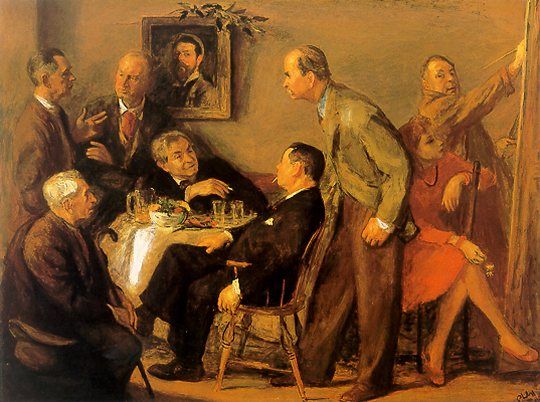

Notable is the genial romanticism of a large canvas, Homage to Sargent, painted in 1956. It is a reference to Henri Fantin-Latour’s nineteenth-century homage to Delacroix and the shared admiration for a master. Homage to Sargent is a bravura work, an ambitious gathering of Philipp’s colleagues. Standing in conversation at the left are Stewart Klonis, whose term as executive director of the League correlated almost precisely with Philipp’s employment there, and John Carroll, a League instructor. Seated around the table are the artists Louis Kronberg, Ivan Olinsky, and Brackman. To their right, leaning forward, is Sidney Dickinson, who, like Philipp, was a portrait painter with a Carnegie Hall studio. Rochelle, Philipp’s wife, sits and watches admiringly as her husband paints himself into the picture. Seated behind her and facing in the other direction, cigarette dangling from his mouth, is Brackman, her former husband and Philipp’s longtime friend.

Homage to Sargent hung in the League lobby when I studied there; one passed by it often enough that its merits were soon taken for granted. By 1980, it seemed to belong to an earlier era of realism. Notwithstanding the presence of Rochelle, it’s a chronicle of male bonhomie; one suspects the inclusion of Sargent was an after-the-fact excuse to gather friends. Eight years later, Raphael Soyer riffed on the same idea with a more formal assemblage of artists, this time paying respects to Thomas Eakins. Soyer’s painting features a larger, illustrious cast, and is more manifesto than fraternal gathering. It is intriguing to wonder if this was at least in part a response to an old friend and rival, which could help to explain Philipp’s reaction when Wickstrom brought up Soyer’s name one day in class. “‘DON’T YOU DARE!’ he shouted, shaking his cane at me. He was really upset.” Soyer recalled visiting Philipp often at his Carnegie Hall studio, where they drew and painted one another in the 1940s. “He was,” wrote Soyer, “difficult, abrupt, arrogant, argumentative, unyielding about his artistic beliefs, yet underneath all the abrasiveness the Robert Philipp I knew, liked and admired was a man of enormous vulnerability.”

“When I first started Robert Philipp’s class,” Mary Beth McKenzie remembers, “he picked up a giant brush, said, ‘You’re not seeing the light on the model,’ and used practically a whole tube of flake white on my painting.” McKenzie evokes Philipp’s strengths as a painter and as an instructor. Her warm appreciation, excerpted from her book A Painterly Approach, is as good an epitaph as a painter could hope for.

Robert Philipp had a tremendous influence on me. While I was still in his class at the National Academy of Design, he asked me to pose for him at his studio in Carnegie Hall. I have such fond memories of his studio, crammed with paintings of various sizes and various stages of development. I learned so much from this experience, watching him paint, seeing the paintings develop, and also getting to know him, which I did over the next twelve years. He was seventy-five when I met him, and his remarkable enthusiasm and excitement for life as well as for painting was contagious. I never left his studio without feeling a renewed motivation and inspiration. He really enjoyed the act of painting, and through his bold handling of paint I became aware of a more sensuous side to painting, a lushness of paint surface and a beauty of color. I loved his loose, seemingly effortless way of working…. Being around him made me realize that painting is a way of life; and the faith he showed in me also encouraged me to believe in myself as an artist.