This year is unlikely to yield a more admirable exhibition of twentieth-century figure drawings than those on display in Paul Cadmus: The Male Nude, now at D C Moore Gallery in Chelsea. Cadmus is best remembered as a satirist—if not an agent provocateur—whose career was launched in 1934, when Navy brass took issue with his depiction of sailors on shore leave. The tightly clad and slightly ridiculous figures in his paintings summon multiple references. Mantegna and Signorelli were cited by Cadmus himself, and much of his early work finds parallels in contemporaneous New York artists like Reginald Marsh, with whom he shared the determination to fuse Italian Renaissance influences and modern urban subjects.

Though he bristled at being typecast as a “gay artist,” homoeroticism runs through Cadmus’s work, be it the narratives he painted for public view, or the intimate drawings that make up the current show. Despite the stigma and even the legal restraints applied to homosexuality throughout Cadmus’s life—same-sex relations weren’t decriminalized in New York until 1980–his art was as matter-of-fact a celebration of the male body as was, say, Renoir’s adoration of the female.

Cadmus was born in New York City in 1904. His parents were both artists—his father lived his later years as a member of the Old Lyme artists colony. In 1919, Cadmus began six years of study at the National Academy of Design, taking classes in cast drawing, life drawing, and printmaking with William Auerbach-Levy, the great caricaturist. He worked as an illustrator and layout artist while continuing his studies at the Art Students League of New York, where he met Jared French, who was also studying at the League. They traveled together to Paris in 1931 and spent the next two years touring Europe, settling for a while in Mallorca. It was there that Cadmus painted scenes remembered from his life in New York, YMCA Locker Room and Shore Leave, ambitious multi-figure compositions that explored themes outside the boundaries of Depression-era social realism. He also painted a loving and unusually naturalistic portrait of French in bed reading James Joyce’s Ulysses. He rarely painted anything so personal again.

On his return to New York, Cadmus joined the Public Works of Art Program and painted The Fleet’s In, a seedy burlesque of sailors on shore leave (he approached the subject again, and better, in Sailors and Floosies in 1938). A retired Navy General Admiral sent indignant letters to newspapers, and the controversy kickstarted Cadmus’s career. “I don’t think admirals,” he said, “have much sense of humor.” Be that as it may, Cadmus continued painting subjects throughout the 1930s that pissed people off, sometimes on the government’s dime. Herrin Massacre, commissioned by Life magazine, announced the brutality of its subject—union workers killing “scabs”—with an adolescent fascination for muscular bodies and bloodshed. A far better application of Cadmus’s penchant for the grotesque was To the Lynching!, a drawing that places the viewer in the claustrophobic vortex of the most dreadful racist violence.

How do the figure drawings relate to the paintings that made Cadmus a celebrity? Put another way, what’s the correlation between the private and public work? Of course there’s the sexuality. Initially, the fuss was reserved for the dalliance of sailors and prostitutes, and nobody seemed to notice the interactions between men. In “Paul Cadmus’ Art of Cruising,” Ignacio Darnaude wrote that “the most striking thing about the Fleets In! scandal is that no one mentioned the homosexual subtext of the painting.”

Woven into this subtext was Cadmus’s lifelong appreciation for Italian Renaissance imagery, especially the presentation of the male nude. The inherent problem for artists with a classical leaning is the awkwardness of superimposing antique poses onto scenes of modern life. One answer is to acknowledge classical tropes while satirizing them, as Cadmus often did in his paintings. In his life drawings, a resolution is found within the intimate give and take of artist and model. Often that model was Jon Anderson, Cadmus’s longtime companion, who described their working process as a collaboration:

A drawing would go on for about ten or twelve hours, divided up over two or three days. First we’d have to decide on a pose —we would work it out together. Paul would say let’s play around with a space or let’s do this and I’d get into something that he liked and we’d start narrowing it down, getting things just right. We’d work, have lunch, then go back and do some more. I’d hold the poses for about twenty minutes. While taking breaks, I’d look at the drawing. There were no rules about anything. Sometimes we worked all afternoon, sometimes we’d just stop and have a cocktail.

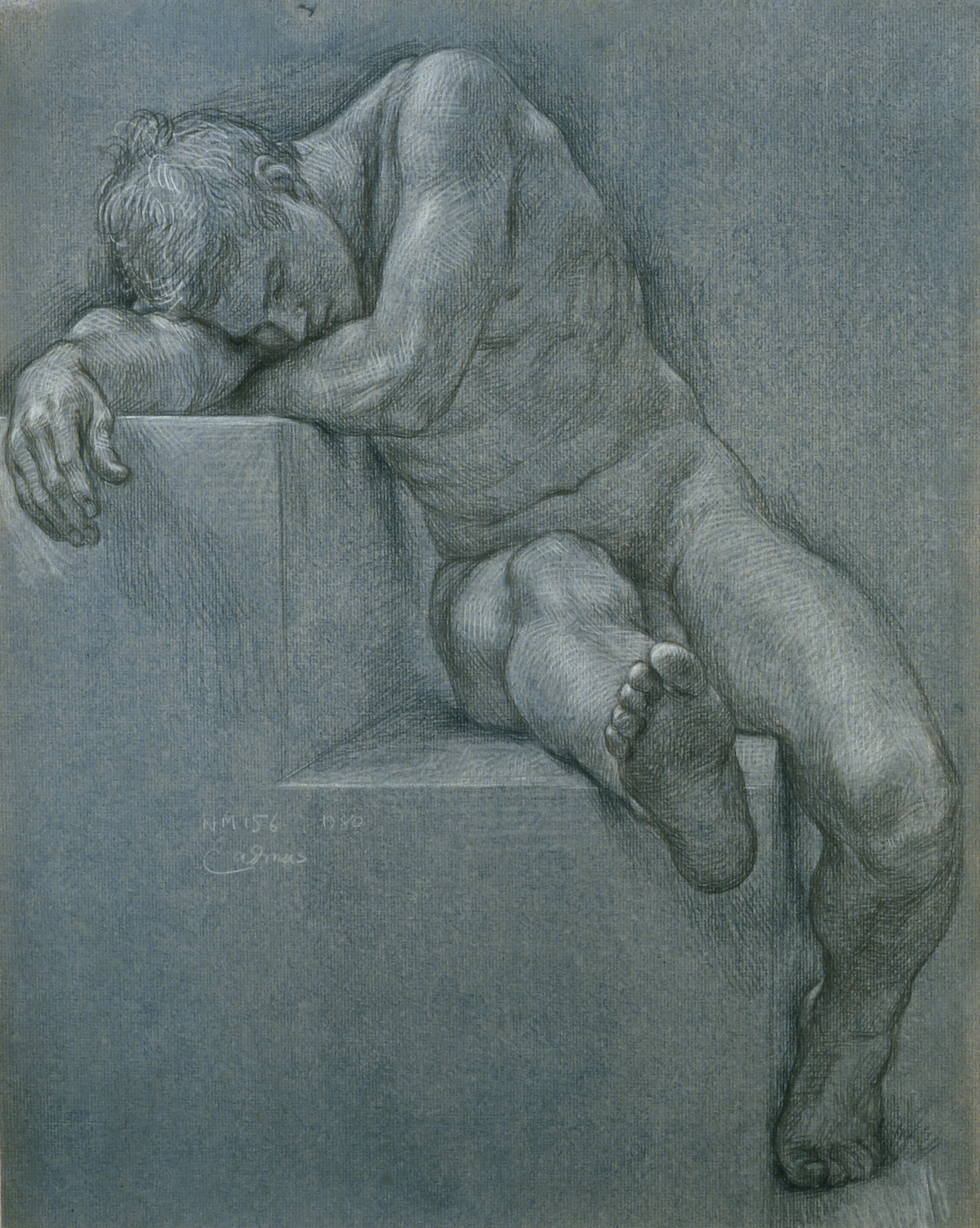

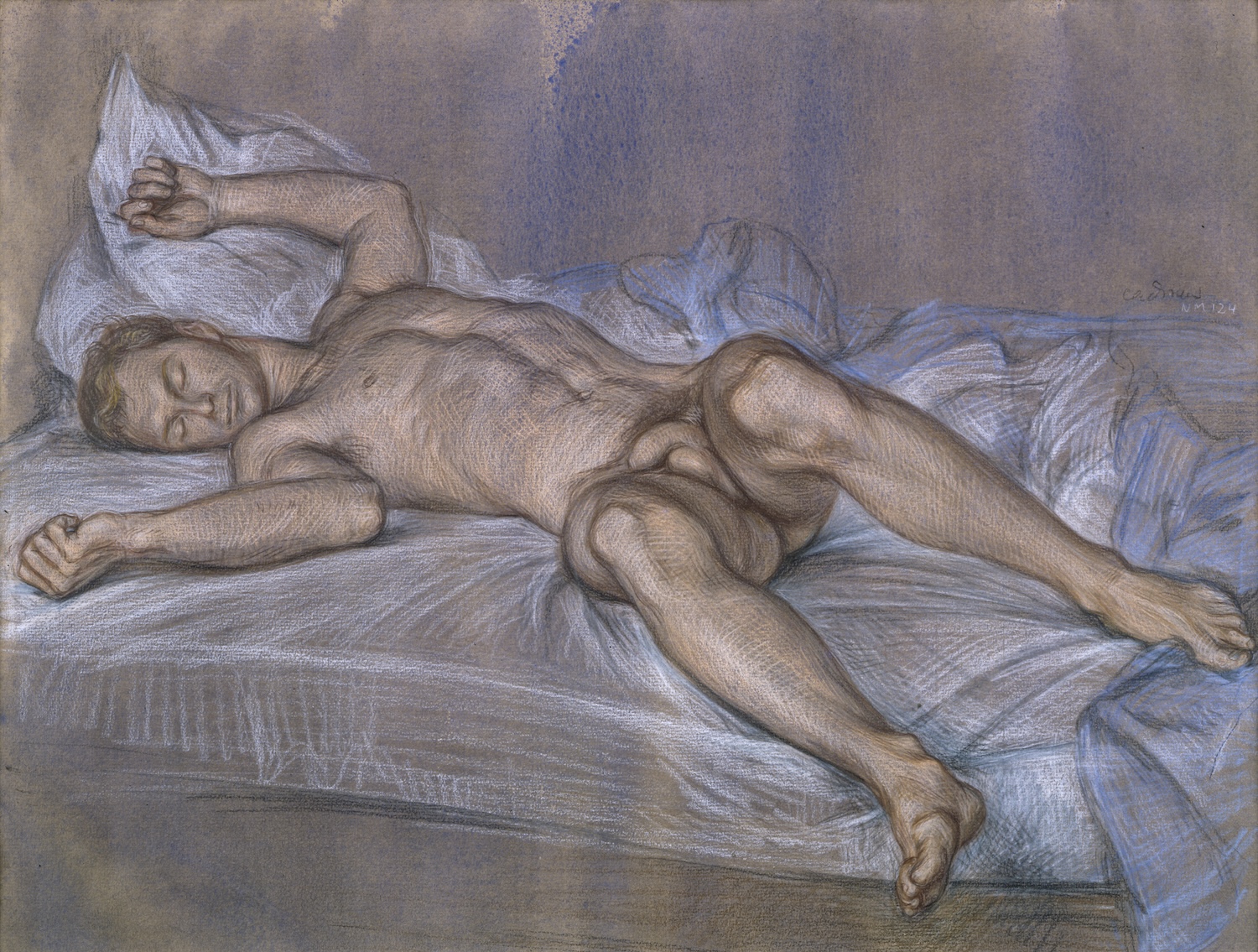

For the most resolved drawings, poses were carefully choreographed and composed to fit specifically shaped hand toned sheets, then drawn in chalk, sometimes supplemented with casein paint and ink. Some drawings, like Male Nude NM156, are contrived to celebrate dramatic foreshortening and emphasize the figure’s heroic appearance. Lassitude is the abiding feature, whether the body is drawn reclining in profile (Male Nude NM247); artfully sprawled on a sofa (Male Nude NMA); or in less decorous display (Male Nude NM124), in a pose Lucian Freud would later adopt for a female nude, Naked Solicitor. The draftsmanship is of a high quality, with an attention to anatomical detail that never looks fussy and an atmospheric impression that’s all the more remarkable, given that every mark was made with the point of the chalk. There’s no chamois, smudging or massing. Each figure and its surroundings are evoked by networks of finely hatched strokes of chalk, a virtuoso effect as nuanced as Cadmus’s paintings are broad. From 1940 on, Cadmus painted almost exclusively with tempera, which induces a similar hatching technique. The intention of the drawings, their attentiveness to muscle and bone, skin tone and lighting, the grandeur of the body at rest, seems to invite a shared intimacy, and strikes a vastly different note than that of the paintings.

In addition to the later figure drawings that highlight the exhibition, there are smaller, more spontaneous studies, several of which suggest the informality of Watteau, as well as a suite of three etchings of stylized nudes cramped into nearly square formats that look like something out of Holbein. There’s also a wall of fine etchings from the 1930s and 40s of urban subjects and Y.M.C.A. Locker Room, painted in the early days in Mallorca, which depending on who you read, is either laden with homoerotic signaling or not.

At the top, I called Paul Cadmus’s drawings “admirable.” They’re beautifully crafted and have a controlled sensuality, yet one misses the variations in emphasis, the balance between resolution and shorthand that allows a work to breathe. In these drawings, tension is distributed evenly throughout the body, and each form is equally prominent—everything is explicated. And a little clinical.

“I don’t know,” said Cadmus, “whether your feelings are erotic toward the model whether that would make it a better drawing or not. It might make it worse, I’m not sure. The cooler you are, maybe the better you draw.”

“Gayness,” Cadmus wrote, “is not the raison d’être of my work.” But neither is sexuality a draftsman’s sole means of engagement with the model, and an attempt at objectivity may screen out other emotions as well. On first sight, I thought these sensitively rendered studies were a personal record of a suppressed culture—the male gaze of the male nude. A few days later, I’ve come to think the drawings may be best appreciated as skillful academic exercises.

Paul Cadmus: The Male Nude is on view at DC Moore Gallery through March 16, 2024.