For an artist visiting Picasso in Fontainebleau at the Museum of Modern Art, it takes a beat or two to get past the show’s initial hook: Picasso spent the summer of 1921 painting in a garage. He leased a villa in Fontainebleau from July 1 to October 1, and in precisely three months produced an astonishing array of drawings and paintings in an adjoining garage he’d converted into studio space. In those summer months, Picasso created the four very large canvases central to the exhibition, and a trove of smaller pieces, all in a space measuring under two hundred square feet. Those of us devoted to lofts and skylights may feel a little sheepish about our ambitions, or maybe relieved. The art thing can be done anywhere.

Since this is Picasso there’s a lot to unpack, beginning with the exhibition’s premise, the disparity between two styles that had long occupied him. One was the neoclassical manner he’d adopted since visiting Rome and Naples in 1917, the other a revisiting of synthetic cubism, an outgrowth of the movement Picasso had co-founded in 1907. There was one other major theme during the summer of 1921, that of the artist’s newfound domesticity, which is amply represented here even as it is treated peripherally.

The show focuses on Three Women at the Spring and associated works, and Three Musicians, of which Picasso painted two versions. That the compositions feature trios is the extent of any obvious correlation. Three Women and the full-scale drawing on canvas that presumably preceded it are funky riffs on classicism, Picasso’s robed giantesses striking Greco-Roman attitudes. The extended hand of the standing figure at left, finger looped inside the ear of an amphora, is so satisfying that it distracts from the anatomical improbability of her bent left leg. So be it; the spell of elegance struck by that hand is broken by the boneless paws of her companions. To see this as a u-turn to classicism, as some feared at the time, is to give the artist’s penchant for play short-shrift. It’s not as if these women bear a resemblance to academic figuration. Picasso once claimed that it took him four years to learn to paint like Raphael, so a little thing like reshaping ancient art wasn’t going to cost him much sleep. Which is not to say he took his play lightly. A series of preliminary works reveals a number of attempts to resolve the composition, running quickly through various poses and schema before arriving at the main canvas. There are also a large painting and related drawing, each titled The Spring, that look like warm-ups for Three Women. They, too, balance satire and enchantment, weight and delicacy.

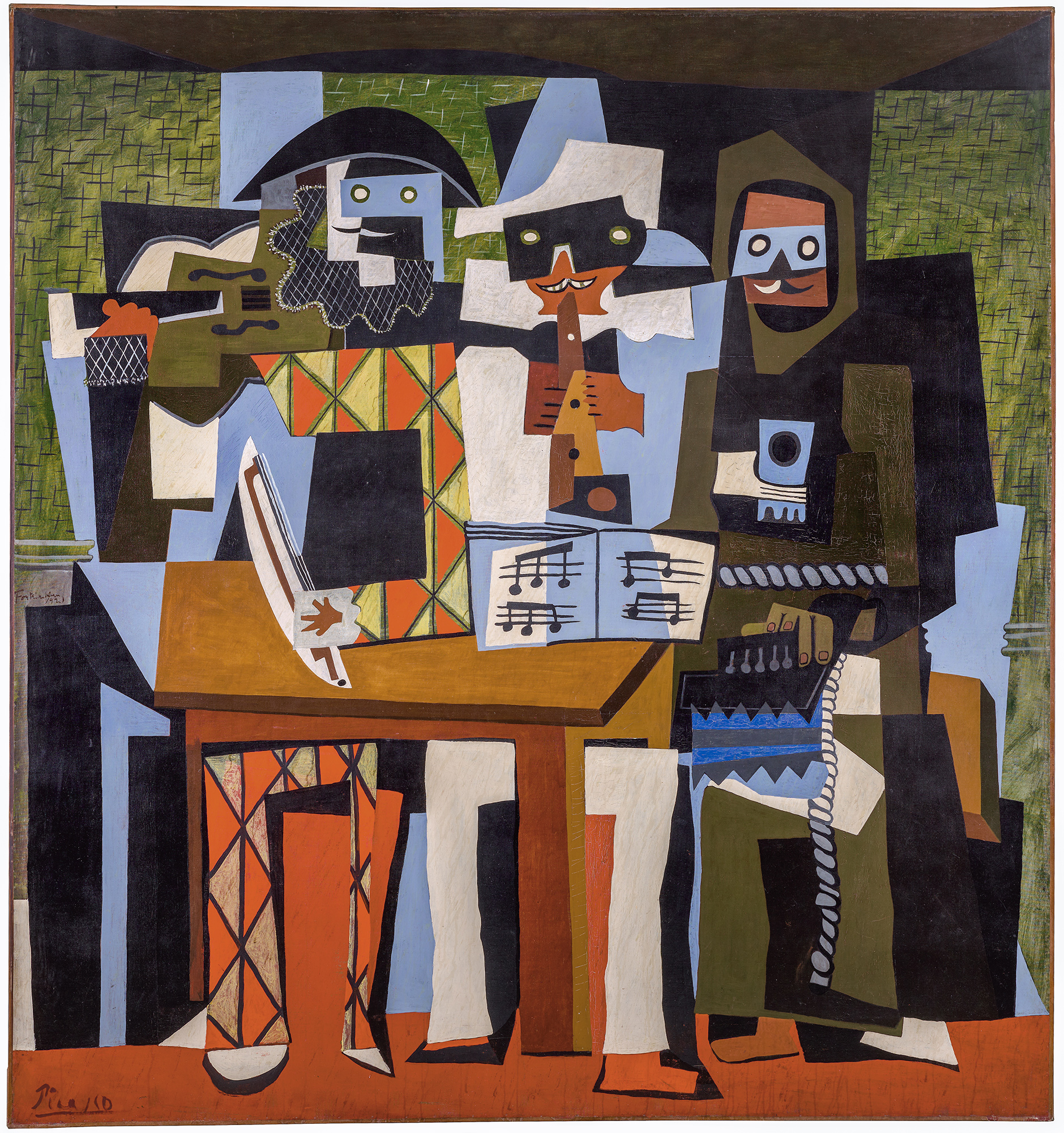

The complement to this abundant femininity was Three Musicians. Both versions show trios whose players face us directly, and are composed of jangly, overlapping shapes that look like collage cutouts, hard-edged and flat. MoMA’s canvas carries the stronger suggestion of three-dimensional space, the figures of Pierrot, Harlequin, and a monk set upon a platform, behind which is a dark wall. The body of a guitar supplies the painting’s sole curvilinear form, with the possible exception of the elliptical mark that indicates a resting dog’s upright tail beneath the center figure. The Philadelphia version is yet more fragmented, the figures jostling one another for their places on the same plane. At the center, Pierrot plays a clarinet that flares into the profile of a woman’s head. Supporting the Three Musicians are several earlier cubist pieces and a few related still lifes, but no line of preparatory studies charting the progress that led to the large canvases. Their appearance derives from costumes Picasso had designed for the Ballets Russes dance company in 1920, which suggests the idea had been brewing before he arrived in Fontainebleau.

For a lesser artist or a less formidable personality, the discrepancy between the Three Women at the Spring and Three Musicians might have been a cause for concern. For Picasso, moving from one to the other must have been akin to playing different instruments—a piano in the morning and a guitar in the afternoon, as it were—on which he could practice alternate themes. Great artists are apt to change lanes, none more often than Picasso. “Whenever I had something to say,” he explained, “I have said it in the manner in which I have felt it ought to be said. Different motives inevitably require different methods of expression.”

What’s open to discussion is whether he was merely (if “merely” is an adequate description for such a facile shuttle) alternating between classicism and cubism, or playing with feminine/masculine prototypes. Or both. “The bodies of these three protagonists in Three Women,” noted curator Anne Umland, “are as volumetric and sculptural as the Three Musicians are flat.” Picasso’s wife, Olga Koklova, had just given birth to their first child. Perhaps by the summer of 1921, the artist saw woman, tellingly placed beside a wellspring, as three-dimensional in her roles of lover and mother. By comparison, man is a character from the commedia dell’arte, engaged in the creative act, but ultimately insubstantial. As works rapidly emerged within the small garage, the artist may have grappled with his sense of male primacy. Umland’s observation that the paintings “would have towered over the five-foot-four-inch Picasso as he worked on them,” provides a poignant counter-image to his lifelong desire for dominance.

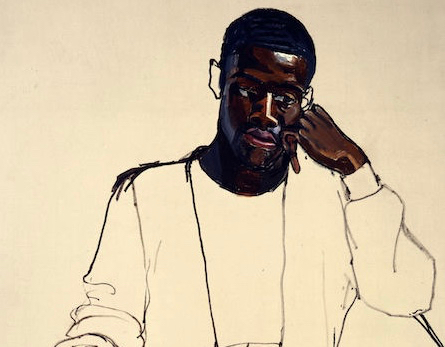

The peripheral subject I referred to earlier, that of domestic life, was more than a contextual backdrop to Three Women and Three Musicians. The exhibition’s first gallery contains the most intimate works of the summer at Fontainebleau, line drawings of the house’s facade, garden and interior, and several of Olga and their newborn son, Paul. These were drawn in rapid succession near the end of the first week of July, when the artist was acclimating to his summer digs; the best is an endearing depiction of Olga bottle feeding Paul, dated July 6. Four days later, Picasso painted the large Maternity, and we see how quickly personal observations are brought to the studio and synthesized into something monumental. If the painting was intended as a tribute to motherhood, it is also disquieting. Instead of returning his mother’s adoring gaze, the giant infant stares off into space. He barely fits on his mother’s lap, and is held in place as much by the flamelike black shadows of her robe as her oversized hands. It’s possible that Picasso was tweaking the sanctity of traditional Madonna and Child imagery, but it’s hard to ignore other readings. The following day, July 11, he returned to the theme in a sensitive drawing of Paul held in Olga’s hands (One envisions the artist amassing raw data, drawing from life in the house, then walking to the garage to paint). Two weeks later, Picasso produced another maternal image, a finished pencil rendering of an oversized, comically unattractive baby on his mother’s lap. Although these depictions of maternity feature physical distortions similar to those in Three Women and The Spring, there’s an additional awkwardness to Picasso’s undertaking of the mother and child theme, as if the infant is an intrusion on an Arcadian realm over which women had previously reigned. Soon thereafter, the marriage deteriorated, though Picasso and Olga remained legally wed until her death in 1955.

Picasso took heat from the avant-garde for adopting a bourgeois lifestyle, and for his continued interest in classical motifs. As the curator notes, there’s a difference between referencing—and skewing—classical tropes from the antique and painting in a technique that prioritizes rendering, like that taught in nineteenth-century ateliers. The latter was the foundation of Picasso’s training, and though he didn’t abandon figuration, he never fully engaged the mimetic dialect of academic art after his adolescence. He was looking to antiquity, and to Ingres. I like to think Corot was in the mix, as well.

Picasso was defined by his willingness to overturn tradition. He made his bones by digesting the example of Cézanne, flattening form before shattering it altogether. When he reassembled the pieces, as in Three Women at the Spring and Maternity, it was perceived as a conceptual retreat. But the reassembling was accomplished on Picasso’s own terms, and the traditions were of his choosing. And if need be, the alchemy that produced both shattered forms and those made whole could happen on summer vacation, in a garage.

Picasso in Fontainebleau is on view at the Museum of Modern Art through February 17, 2024.