Rhoda Sherbell attended the Art Students League in 1951–52, studying with William Zorach and Reginald Marsh. She became an instructor of sculpture at the League in 1988. Over the course of her career, she has had twenty-two solo museum shows, exhibiting at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, the National Portrait Gallery, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and the Museum of Natural History. Among her thirty-nine awards are a Ford Foundation Grant, the Pennsylvania Academy of Arts Award, and the Louis Comfort Tiffany Award.

Ira Goldberg: When did your relationship with art begin?

Rhoda Sherbell: It began with my father wanting to be an artist. He wanted to paint all his life, but being a fur worker, he had to make a living for the family. He couldn’t do it all, so his aspirations went into his children. My mother was an opera singer, a mezzo soprano.

IG: Was your mother a professional singer?

RS: She performed at Radio City Music Hall and also at concerts. She sang at the Brooklyn Museum, at the great rotunda there. And while she sang at the rotunda, I would just disappear and would run through all the rooms. The greatest room for me was the Egyptian room. I was eight years old. Art was something we were introduced to at a young age: the Hudson River School, the Ashcan School. My father took us to the Brooklyn Museum, which was walking distance from our house. We’d go there down Eastern Parkway every weekend in the winter. That museum taught me more than anything else because the collection there is really verbose in every way. It’s next to the Met, I think, in terms of its scope in the metropolitan area, if not the country. So when my mother sang, I would go into the Egyptian room. They knew me. They got so used to seeing me and would let me hold the sculptures, even sit on them. If I saw a cat. I would sit on it, put my arms around it, and feel its volume. I would touch things. I would look at the sculptures of Pharaoh Thutmose. I would put my hands over the sculptures and just feel them and get the opportunity to understand volume, scale, touch, cold, you know, materials. Then my father would show us the Ashcan school and painters like Gladys Rockmore Davis, that whole group. It became like brushing my teeth everyday. Art was a constant.

My father also loved Rembrandt. He would take us to the Met to see the Rembrandts. Now for a little girl to have to look at Rembrandt is very difficult. It is murky in color. It’s people who look like they are suffering somewhat. I wasn’t too attracted to Rembrandt. I would run away to a room that made me feel good, one of the Egyptian rooms. In my home, there was so much conversation around the arts. There was such a passion in the house; it was hard not to think of art as much as doing math and English in school. It was just part and parcel of our daily life. It was spoken about at the table. It was something that I felt was so endemic to me as a child. Then I learned about the Art Students League. How did I learn about the Art Students League? I looked at the work of William Zorach in books.

IG: Were you always attracted more to sculpture than to painting?

RS: No, I wanted painting much more than sculpture.

IG: You were talking about your experience in the Egyptian rooms and the tactile nature of sculpture, which seemed to be your immediate attraction.

RS: All of the art was an attraction to me, wherever I went. The color would excite you. The themes and content of the work would excite you. There was storytelling that I didn’t completely understand, and I didn’t have anyone to explain it to me. You had to go by what you were seeing and your feelings. This all built up. As I viewed these artists, they were pushing us at Washington Irving High School to know more about art history and to do practical work.

IG: It sounds like you know from the get-go that you wanted to become an artist.

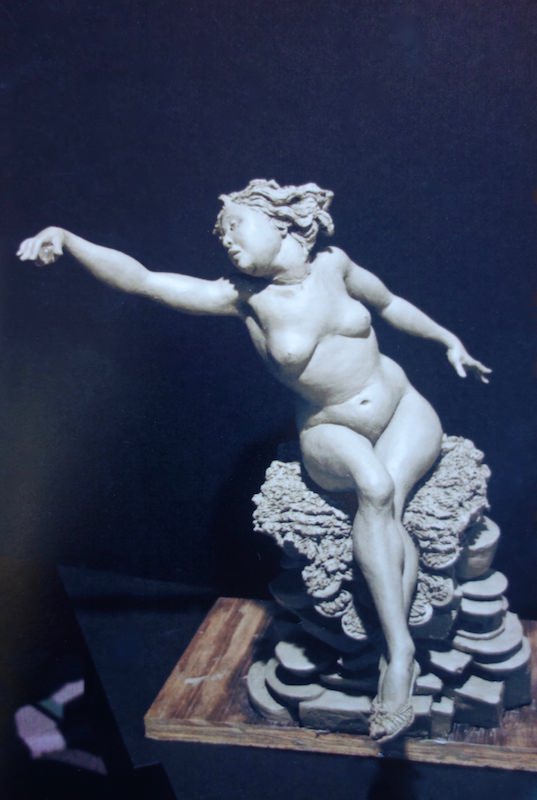

RS: Oh, from the very get-go. It was automatic that that would be my life. I just felt that there was nothing but art. I did want to pursue dance for a while. I did go with a dance group to study modern dance, Ms. Pearl Primus, a modern dancer. I was being exposed to everything. What I did get from that, and what I try to give my students today, is an understanding of how these art forms are absolutely related to one another. The aesthetics, composition, storytelling, and movement.

If you listen to the composer Wagner, he is a great master, one of the greatest masters of all in my opinion. When I work, I put that music on for my students, and I tell them, What do you hear in that music that you have to know in sculpting? Or, if you’re a painter? The same principles are at work. You have to know what a staccato is and how to make a stop in the work, and how to make glissando, which is a long line, and how to make a rhythm or melodies work in your sculpture or your painting. The same principles are always at work. Sometimes I bring in books. I bring my students to the Met on rare occasions, and I show them these things. I show them the correlation of the artwork and how it works in all the arts because they are all completely related and entwined. It is really a journey that’s quite wonderful.

You asked how did I got to the League. The League was something that seemed to me always a bright star because of the teachers. I would look at the work of different artists in books, and they were always at the Art Students League. My parents said to me, Rhoda, we know you love art, but you have to go to Cooper Union. You have to become a teacher. We want you to have a livelihood. But I came here. I knew I wanted the League. So, I put a portfolio together.

I will say my parents were unusual because they felt it was a great honor to be an artist, to be able to accomplish something and to “speak” in your artwork about things that were significant.

IG: What year was this?

RS: It goes back a long time: 1953. I walked by the school and came in. I didn’t know if I was going to get in. I just said, I want to be here. I love this place. I didn’t think my portfolio was good enough, but I did get a scholarship.

IG: From the outset? Whom did you show the portfolio to?

RS: I just brought it in and asked, Can I leave my portfolio? They said yes. I was thrilled. I didn’t take a receipt. I was just thrilled to leave it here. When I got the scholarship and I could study with Zorach and Reginald Marsh, I was beside myself.

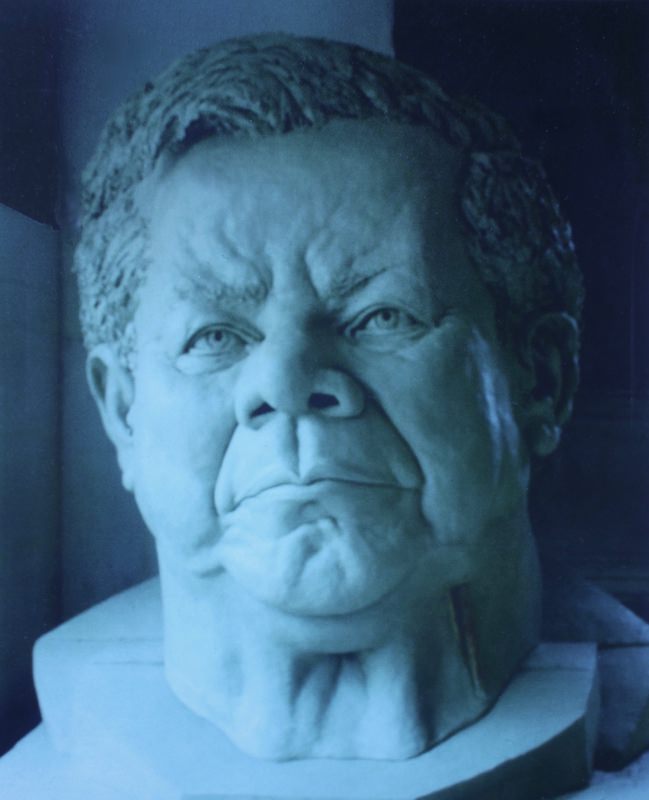

The first day I went into the studio with Bill Zorach. He did a portrait of me. He said, You look like a Zorach. That was the beginning of a friendship with William Zorach and his wife Marguerite. To the day they died, we were very close friends.

I have photos that I can show you where I helped Zorach at a certain point. Artists sort of fall out of favor over the years. Andy Warhol is great, but he wouldn’t have been great at the time of Reginald Marsh. They would have looked at him as a flat artist. What is this about? We always have this constant shift and change in the art world, which should mean nothing to any artist because that is not what art is about. Art is what you deeply feel. For me, I just felt I had to say something, and I wanted to be a communicator. I am a talker, as you well know, and as my students well know. But I like to talk in my art too. It is very important to me that I can communicate—and that word I put in capital letters—that whatever you say would have to have some kind of meaning that a person could respond to. And how did I come to this first, in my own emotional and intellectual feelings, and then, when I visit the Met Museum, or the Brooklyn Museum, or any of the major museums anywhere around the world? What I always do is step back. If I am watching the public go by, and I’m looking at all the wonderful paintings, no matter what room it is, what period it is, it doesn’t matter. Take it from Degas to Cycladic art. I don’t care where you are. See how long the public will stand in front of a painting or sculpture. Very often you’ll notice that they come in and they keep walking, they keep looking, and they keep walking. What stops someone and holds them in place? What paintings do that? What sculptures do that? And you’ll find in any major room, in any museum, that the public will pass many works of art and they will stop at certain paintings that hold them. We ask, What in that painting in holding their attention? Why is that painting speaking? That is for the artist to analyze and to understand.

IG: Don’t you think that part of it has to do with the viewer?

RS: Well, I was looking at it from the point of view of the many people walking through a museum—the aggregate. When art really speaks to you, it is usually to an artist. That’s been my experience, and I’ve been around writers and composers. I’ve been to many places where there is a complete mix of artists doing their thing. I was close to Aaron Copland, and I worked at the MacDowell Colony. I’m not going to drop names. There are so many talented artists whom I was close to and worked with. There is something we all have in common. We’re not driven like the rest of the population. We’re driven to look at the things differently. Give me your favorite artist. Just any one of them.

IG: Titian.

RS: Which Titian do you like most of all? There are so many beautiful ones.

IG: Equestrian Portrait of Charles V in the Prado.

RS: It’s gorgeous. It’s amazing. What holds you to that painting?

IG: Things that probably that I couldn’t describe. The presence of it, the regal quality in which the king is portrayed that has everything to do with the composition, his relationship to the horse. When I see it, its strength overwhelms just about everything around it. So I can speak in sort of rhapsodic terms. That painting now is in the Prado there is this great rotunda where the Velázquez paintings are. Las Meninas is on the opposite wall.

RS: I cried when I first saw it.

IG: In that room it’s all Velázquez. Then when you go back out into the main hall, there’s the Charles V, the Titian painting. When you see that, there is a grandeur that I just find indescribable. It’s hard to be able to look away from Las Meninas at that painting and be overwhelmed after you’ve seen such a great work. And yet there it is.

RS: And there it is touching you, deeply.

IG: What is it about it? It is all of that and more. If we can go back and diagram the painting, the composition, the juxtaposition of forms, then we can break it down, it is always greater than the sum of its parts. It is difficult to respond to that question. The work has to hit you, and you have to be open to being taken by it.

RS: What you say is one hundred percent true. When I first looked at Las Meninas—I’ve seen it reproduced in books forever—I thought it was painted very flatly. When I went to see it and walked in the room, the first thing I did was cry. I couldn’t believe that I was really in front of it. When I got very close to it, what surprised me was the impasto. The amount of free brush strokes that Velázquez used—though not in the faces. I found that he works in two different ways. The faces are done with such refinement, and almost what I would say, with like a small sable brush. And then he gets to the body, or whatever other parts, and he takes brushes and he just slapdashes it on. It is so free. I wondered, How is it pulling together? Up front, very close, it did not pull together. So I walked many times back to the door, and I looked at it from the door, and it just gelled.

IG: How long did you study with Zorach?

RS: The friendship I had with the Zorachs lasted well beyond the time I spent at the League. They invited me and my family up to Maine. I was with William Zorach when he got sick. Marguerite, his wife, would call me up and say, Rho, you’ve got to come because you perk him up. She said he would even put on a tie when I would come. He let me work with him in the studio. It was very hard for me because he worked very large, and, at that time, I was not used to working on a large scale. He was doing sculpture, pieces for outdoor monuments. Whatever he said to work on, I never said no to. If he wanted me to do a whole thigh or a leg, I knew how to do it. I always instinctively knew the figure. Somehow I always knew what I was doing. People would say, How did you get to that? What is that? I would just get into something, and I just knew. You know, I would just look at it, and, boom, I see things very quickly. That’s also a part of teaching: to see things instantly and to know the correction without injuring the piece. That’s something that I think I was born to, if you could say such a thing. I had a grandfather who carved furniture. They didn’t call him a sculptor in those days in Russia. He was called a craftsman, but he was basically a sculptor. My sister writes. My brother is a photographer. We’re all involved in the arts. In my family it’s a shanda (shame) not to be an artist.

IG: That’s very unusual, even back then. Parents want to know that their kids will be self-sufficient, to be able to make a living.

RS: I will say my parents were unusual because they felt it was a great honor to be an artist, to be able to accomplish something and to “speak” in your artwork about things that were significant. In other words, you couldn’t be a luftmensch (airhead). You had to have ideas and purport those ideas so you influenced others. You had to be a teacher through your art. That is the way I was brought up. I know that’s unusual, but I also felt I was different from other students and other young people. My parents would put art books in front of us and say, Read it and then explain it to us. Art was always an ongoing conversation in our home.

IG: So after apprenticing with Zorach, what was the next step in your career?

RS: Zorach did some really lovely things. He took me to galleries. He called up Victor D’Amico at the Museum of Modern Art, so I could teach in two-week program. It was a ball. I didn’t know that I could teach, and I didn’t know that I could enjoy teaching. The museum played wonderful classical music while I was teaching. Now I was getting the feeling that this is really a good time. When I came to the Art Students League to teach, I felt that I was at home.

IG: When was that?

RS: It was in 1988. I didn’t realize how much I could communicate with students. And I have the noisiest class in the Art Students League, no question about it. My students are very communicative. They talk across the room. We are very open with each other in my class. I don’t think anyone here teaches like I do. It’s a very open, free environment. I’ve never had a quiet room. They will talk about anything, always art-related. Their fingers are always working.

IG: When you were hired to teach, you had already established some professional credentials. Let’s go back to your apprenticeship.

RS: I had my parents asking, When are you going to break through?

IG: What did you understand “break through” to mean?

RS: When am I going to become a professional? That’s what “breaking through” meant in my family. They had established themselves, and I was expected to follow in their footsteps.

IG: Overachievers.

RS: Overachievers, you better believe it. In my family, you had to be. When we get together, everyone says, What are you doing now? They challenge you on it. So I am used to that atmosphere. It is not confrontational or adversarial. It is actually helping each other.

Since my parents put it to me like they did, I took my portfolio and went up to the ACA Gallery on 57th Street. I went up the steps, threw my portfolio down, and said, If you don’t take me, I can’t go home. My parents will not accept me in the house, so you better take me. They laughed and said, We are taking you. You are a talented young woman. We are going to give you an exhibit. And they actually did, in a year’s time.

I am a humanist in my work. That is very important to me, to always have content, to always be involved in storytelling that is important to other people. Otherwise, why bother?

IG: You were in your twenties?

RS: I was pretty young. I had the show, and everyone and his brother, including Phillip Evergood and the Soyers, were there. Their whole stable showed up, and they all embraced me, like I was a little star. I was a baby. By the way, they never knew my name was Rhoda for many years because Zorach called me “Baby.” Everywhere I went, they said, Baby is here.

IG: Did your parents call you Baby, too?

RS: They called me Rhoda. But everyone else called me Baby. No matter where I went, they said, Baby is here, and that became my name. I was Baby for many years until I said, You know, I do have a name, and it is Rhoda. Please start calling me Rhoda. It took a lot of doing to get to that point.

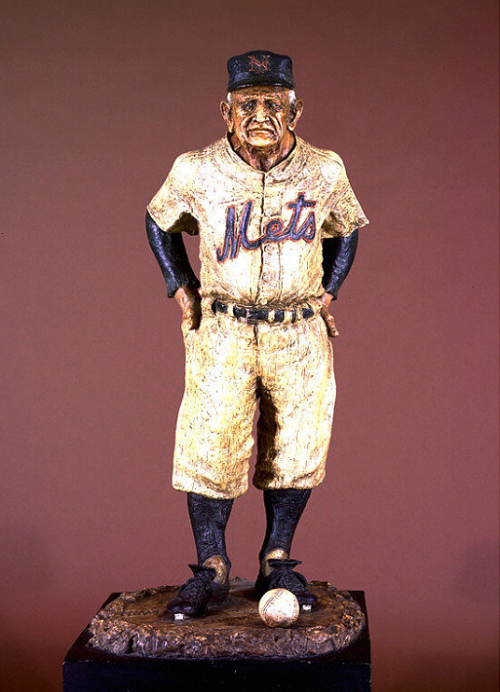

From the ACA Gallery, I got commissions. People were buying; known collectors were were purchasing my work.

IG: What was the theme of your work at that time?

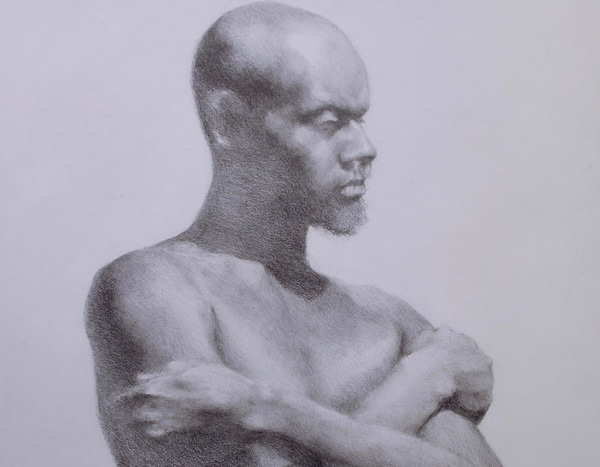

RS: It was realism, basically. It was always figures: figures in action or repose, portraits, sport figures. My basic thrust was always the humanity of what we are about. It is not so much the theme or the idea. Even to this day, I can’t explain it. It has something I don’t even understand myself. It’s the joy of producing a sculpture and getting the character of your subject.

I don’t want people to walk away from one object to another when my work is on exhibit. I don’t want them to walk by and look at something else. I want them to stop and say, What is she saying here? What is she talking about? Why am I looking at this? That has to do with the way that you develop the mood and the content of a piece. Remember, we’re not actors. We’re not expressing ideas verbally; we have to say what we want visually. I know how to do that now. If I want someone to feel enlightened or questioning, I know how to put a couple of things together to express that, and give that clarity. At this stage of my life, I know how to do that. I have that under my belt at this point.

IG: Do you feel you’re doing things at this moment that you might not have been able to do ten years ago? How has this constant state of learning impacted your work.

RS: It has to do with the friendships that I have had. I’ve known people in the field over the years; we talk on and on. At this stage of my life, I don’t want to waste time because I don’t know if I will be gone tomorrow, or gone in a year or ten years. I have no way of knowing this. I have a lot to say. There is so much I want to say.

Currently, I sculpt in my kitchen. The stove is behind me. No one can work on the kitchen table because that is where I work. But there are counters that they eat on around the kitchen. This way, if someone comes in, I am still a mama. I can still say, Yes, what do you need? and be attentive to their needs.

I have friends who constantly call, and even if I am working, I just tuck that phone in, talk, and continue working. It does not stop me from doing artwork if I am talking. I am always comfortable.

IG: The thing that I’ve noticed about artists who’ve spent their lives at art, even as they get into their 80s and 90s, is that the journey continues to open up new horizons, and that never-ending passage provides, for people who create, new territory to conquer. You’ve had great genius artists, like Seurat or Raphael or van Gogh, who died young but accomplished so much. But for those who have been able to continue to learn, it is amazing what can be accomplished in one’s senior years. I find it fascinating to observe.

But let’s go back for a moment. Were you making a living from this early work?

RS: Hammer Galleries came to me. Frank K.M. Rehn Galleries came to me. I had a show at the Huntington Hartford Museum. I’ve had, let me see, over twenty-five solo exhibitions to date. That’s a lot of solos. The galleries sold my work and a number of major collectors became my patrons and were fans of my work for years—actually, until their deaths. It became a steady source of income.

IG: At private galleries?

RS: At galleries and museums. I’ve had the opportunity to focus on that community, which is very unusual. They’ve given me complete freedom. No one has ever said, You’ve got to do this; you’ve got to do that. It gave me great confidence that whatever I was doing, they felt, had merit. Then again, for myself, I always held out the word “standard,” which is quite important. You have to hold yourself to high standards at all times, and you can’t be easy on yourself. There’s no one tougher than Rhoda on Rhoda. I will not accept anything that is lesser. If I am working on a work of art, or I am teaching, or in a conversation, I want it to be perfection. I know that perfection is not a good thing necessarily, but I always want the thing to be the best it can be, no matter what I do.

My late husband, Mervin Honig, was a painter. We had many husband-and-wife exhibitions in museums together. My life is two artists under one roof, and it is nice to see how we juxtaposed against each other, which was a very beautiful relationship. Having an artist husband to me is like the best thing that could happen to anybody, if you’re an artist, because of the conversations, the understanding together of the arts, the sharing, and also the growing of the aesthetics together. The unravelling of aesthetics is very interesting.

IG: Did you ask him for advice? Did he critique your work?

RS: No, I never did ask him for advice, but he did critique my work. I was sort of the more forceful person in the relationship. I was the one who would do the critiquing. I would say, I think that painting is too dark. It is a lovely painting, but no one is going to buy it because it is too dark. So why don’t you think of lightening up somewhere. You find the answer. I can’t give it to you.

How do you find the core, the very essence of a subject?

IG: What would he say about your work?

RS: He loved my work.

IG: You said you didn’t ask him, but he critiqued your work?

RS: He’d always say, You’re a genius. We would laugh, and the both of us would just go on working.

IG: So you’re showing together and having exhibitions. Did you travel?

RS: He wanted to do Bermuda scenes. He loved the water views. I was bored to death in Bermuda. He loved it because it was fulfilling something for him in art. For me it was just relaxing and putting on pretty hats. I don’t work when I go away. My husband could paint anywhere he went.

IG: Not even drawing?

RS: No, for me, I’m observing and gathering. What I am doing is living. How can I put this? My husband, Mervin Honig, was more driven as an artist, day in day out. I am an artist, too, but I don’t have that same attitude about drawing. I just do it because it is there, and I have no choice, so I do it. I don’t consciously think about it. But it is in sculpting that I find my happiness.

IG: You’re not a machine.

RS: No way. I look at people; I talk to people; I’m gathering life experience, what people care about. I like to write because that also goes back into my art. I like to experience other people’s lives. It’s not voyeurism; I’m just curious about other people’s lives. I love Hemingway. Thomas Mann is my most favorite writer in the world. Not only do I love the way he writes, but his paragraphs have unbelievable poetry. They’re so beautiful: his verbiage, his observations. It is like reading and viewing painting at the same time.

IG: So you got sick of Bermuda, and you went to Italy.

RS: I love Italy very much.

IG: When was the last time you were there?

RS: It’s hard to believe, almost forty years ago.

RS: The first Italian trip was to Venice, stopping at little fishing villages to see how people live. Every part of Italy is beautiful; I just can’t get enough of that country. France is lovely. But I would like to go back to Italy just to reacquaint myself again with that culture.

IG: How did your experience in Italy impact your work?

RS: I’ve looked at Italian paintings all my life. It’s very inspirational. Just being in Italy, just going to the Vatican, or going to the Uffizi. The Uffizi—you can’t get yourself out of there! I wanted to just live there. It was an experience beyond my wildest dreams. At any rate, Italy is a home for artists. I could live in Italy.

IG: Do you think that your work changed as a result of your being in Italy? Or being anywhere else? Or just life experience? Sometimes things happen in a certain place and time that you bring back with you.

RS: I think that no matter where you are or have gone, you are constantly brought back. You are always on that learning curve. If you think you’re not, you’re kidding yourself because no matter what you do, you’re coming back with a new experience or gaining new insight that you might not have at the moment. I wake up in the middle of the night with ideas. Ideas are ever-present for artists.

I look at something and sit down in front of it. And I just sit and look at it. I will find I like something; if I sit, it talks to me. It doesn’t hit me at once. I’m not a person who goes, Oh, wow. I sit down and look. I look at the foot. I look at the way the hand is made. I look at the way the artist played with it. If you observe it long enough, it’s a conversation with an artist, but you have to stay there, and you have to give yourself a chance to have this conversation take place. And it does take place.

There is really no difference between me and the art. I am of one piece. I am not a cook. I don’t go out and dance. I am happy to be in my studio, which is lately my kitchen. What can I do? I yield. I’m a woman. A woman has to.

IG: What is coming next in your work? Have you seen your work evolve?

RS: Yes, I have seen my work evolve. I’m not fully happy with its direction. I’m getting a little too facile, which I’m not happy about. I have to rethink things at this point. Maybe I have to step back. I have to become more philosophical.

IG: You, more philosophical? I don’t know of anyone who is more philosophical.

RS: I do have to become more philosophical because I feel that I am at a plateau. I don’t feel I’m where I want to be. I want to go beyond. I’m not happy here.

IG: Can you imagine what that would look like?

RS: I wake up like three or four in the morning. What’s wrong? Why aren’t you getting what you want? It has been bothering me. I get up a lot and I go downstairs and sit in my garden room. I can just sit and think. When I want more I think, What do I want now? I don’t know at this moment where to go, but I know it is not this. I’m in a quandary at the moment.

IG: How long have you been in this quandary?

RS: About a couple of months.

IG: That’s not that long.

RS: Oh, it is long. For me it is suffering. It’s agonizing. I know what I am doing is not enough. I’m not looking to become an abstractionist. I’m not looking to jump out of my skin to be something that I’m not. I just want more, and I don’t know right this moment what “more” is. Does it make sense if you say that you begin to get tired of yourself at a certain point in your life?

At a certain point, you look over thirty-five or forty years of work. There is a progress; there is a storyline; there is a point-of-view. I am a humanist in my work. That is very important to me, to always have content, to always be involved in storytelling that is important to other people. Otherwise, why bother?

I like to relate to people. That is what I love about teaching. That’s why I continue teaching. The interrelationship you have with all kinds of people from all countries, from all points of view. When you have that, it gives you the opportunity to glimpse new ideas sometimes.

IG: I want to bring you back to the original question, which I think we didn’t quite fully cover. You, having gone through moments of self-judgment and moments where you feel something is too easy. You seem to be critical of your work in that regard. What I also want to clarify is whether there always a narrative in your work.

RS: There has to be for me.

IG: Do you like the work of people like David Smith or Ruben Nakian?

RS: I think they bring a great deal to us. I think we have to value every artist because each is unique. Yes, I value Smith and Nakian. They are great artists and have made significant contributions.

IG: Do you ever feel like you would be able to delve into those areas?

RS: For me narrative content is important because I like to communicate. I like people to look at my work and understand it. I watch people as they look at my work at my museum exhibitions. I watch people look at work in the museums. What I enjoy when I do go to the Metropolitan Museum of Art is watching people look at world art—that is very important because there’s a lot to learn from that. There is a saying that we should all respect, “Of taste, there is no disputing.”

IG: Maybe the narrative is not giving it to you anymore.

RS: That’s the challenge I’m in at the moment.

IG: But then you say that when you just get into nonobjective, it is too easy. I must have a subject other than a square and a circle because that grounds me and tells me where the next step is going to be. It is to find the essence.

RS: How do you find the core, the very essence of a subject? I used to think I got to it, and I did at certain points. At this point I’m not. This has happened to me throughout the years where suddenly I was at bay. I’d say, OK, I’ve gotten awards, I’ve gotten prizes. So what? Who cares? That does not make an artist happy. What makes an artist happy is her production, work that satisfies you. If it doesn’t satisfy you, you might as well change your work, right? That’s the way I feel. I am at an age where I don’t know how much longer I will be here. I say, What now are you looking for? What is important to you and to other artists? But most important, What are you looking for?

IG: Is it possible that you’ve gotten as much as out of the material as you’re ever going to get?

RS: Well, I’ve worked with wood and stone. I paint. I love the clay because it is most sculptor-friendly. It gives you possibilities of going anywhere you wish. It is not a material that is going to exhaust you. A stone, you can just go so far with a stone. You can just go so far with certain materials. Clay is open to anything. I’ve taken clay and I’ve dropped it on the floor just to see patterns. But all I see in it is beautiful patterns.

IG: What has come out of that?

RS: I will make a design that I could add to a background or to the composition.

IG: Is it ever the thing itself?

RS: Never. No. That doesn’t satisfy me.

IG: Are you working on commissions?

RS: I don’t have any commissions at the moment. I think perhaps my last commission took the starch out of me. It was very large. It was 5 feet high and 5 feet deep and was such a challenge physically. My upstairs studio, under its weight, was coming down into the dining room. We had to bring carpenters in to buoy up the room. I am now working in my kitchen.

IG: My kitchen is my second studio. But it’s where I cook.

RS: I think it is the second studio for a lot of artists. I’m working in sizes that a collector could buy and put on a desk in their home. I’m not interested in galleries at this moment. I should be. I generally think in terms of museum exhibitions. I’ve been lucky enough to have a museum exhibition every few years. I tend to work towards what will be shown in that environment. They take some of my work for their collection, and then I think where I might exhibit next. As we know museums give us the longevity that you want for your work. If you are a person who is showing in galleries that’s kind of wonderful, but I think that any artist who wants to have a history in our field, you must be represented in museums’ permanent collections.

Ira: You talked about looking at people looking at art. To me, looking at art is a relationship, a dialogue. The more I’m able to see, the more it communicates.

RS:When I go to the second floor of the Metropolitan Museum, I can see one of my favorite artists, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes. I adore Puvis’s work. The reason? I like the scale. I like his compositions. I like his tertiary colors. I like the fact there is so much poetry in his work. The fact that he uses the Golden Mean in his canvases. It is extraordinary. That sets me up in a wonderful comfort zone when I walk through the second floor. Then, I view Arnold Böcklin’s painting the Island of the Dead. It’s a bit scary and has a different pungent mood.

IG: Do you look at Rodin? He’s all over the second floor.

RS: I love Rodin, of course. How can you not love Rodin? He’s a master of masters. I love everything, when I go to the Met, there isn’t a room, except musical instruments, that’s the only room I don’t go into. The Egyptian rooms are still my most favorite, which goes back to me working in the Brooklyn Museum and to me working with William Zorach as a student. I feel so lucky to have had him as a teacher. I don’t know if other students have had relationships with their teachers as I had with Marguerite and William Zorach. They were caring and supportive. I received all kinds of awards, I didn’t know that I was receiving, and they came through him. He would say to me, Baby, why don’t you put your work into the Pennsylvania Academy. Baby, put it into the Detroit Institute. Baby, put it into the museum of Colby College. And I’d say, fine, and get a new sculpture together, photograph it, see if I could get in the show. If it got in the show, I would get an award, and then they would buy something of mine. He made sure that museum after museum would purchase my work. He gave me status and an understanding that a woman sculptor could make it. I was a teenager when I first came here. Soldiers from the Second World War were signing up at the League. There was Reilly and Kuniyoshi. I think that the teachers who were here were just amazing, as are the ones who are teaching here today.