Ira Goldberg: You came to the League for a month and studied with Alice Murphy, who kicked you out of her class?

Robert Kipniss: No, not exactly; she was a lovely lady. She had set up still lifes, and we were drawing the still lifes and I enjoyed it. She tried to show me things and I didn’t listen.

How old were you?

Sixteen. It was 1947. I had always been drawing and painting because my parents were commercial artists, so there were a lot of materials in the house. And I had an aptitude.

Did you live in New York?

Forest Hills, Queens. Before that we were in Laurelton. I was born in Brooklyn. So I came to the League, and I was in Murphy’s class maybe a month or two. And she said to me one day, I’ll never forget it, very nicely, as she leaned over, she said, You don’t want to learn anything from me, do you? And I said, No, I just want to draw. I was using pastels.

Had you drawn before?

Oh, sure. I’d been drawing since I was three. Lots of drawings.

Any formal training besides observing your parents?

Well, just observing. There had been a book called Guadalcanal Diary by Richard Tregaskis, which he illustrated. I copied those illustrations because I thought they were beautiful drawings. I don’t know about that anymore. I was about fourteen or fifteen when I copied them. Anyway, Murphy said, “You shouldn’t waste your parents’ money. If you come in every Saturday, for fifty cents you can draw from the model all day long without instruction.” And I thought that’s what I would like to do.

Had you been drawing from models?

Never had done that before. As a matter of fact, I saw my first naked woman.

I remember my first time, up in studios one and two. I was startled by the matter-of-factness of getting naked.

I somehow wasn’t. Nothing surprised me, and nothing startled me, and nothing fazed me. I just started drawing. But I had had relations with a young girl, though she hadn’t really undressed all the way. So I had some familiarity with the female form. I drew from the model and really enjoyed it. I found it very interesting. I was able to position it on the page pretty good. What was really interesting is that this place was filled with veterans from World War II. There were some very serious older young men, you know, guys in their twenties and some young women. The two Klonises (Stewart and Bernard) were here. Vaclav Vytlacil, Robert Brackman, and Yasuo Kuniyoshi were here.

I liked coming to the league. I liked the professionalism. I liked the seriousness. And I liked drawing. I liked all these people in this room with a beautiful woman, undressed, on a platform. Everybody was quiet and really focused on drawing this body. There wasn’t a lot of chatter. There wasn’t a lot of visiting. People came in and they drew. They paid their fifty cents. The class was in the big open room in the back of the first floor.

This was still the late 40s?

1947.

That focus you had on drawing the figure was never interrupted with a modernist approach?

No. I was just learning to draw the figure. It was very nice. Sometimes at home I would set up a still life. Or I drew my sister’s portrait.

How did things progress after that?

In September of 1948, at seventeen, I went to college.

Where did you go?

I went to Wittenberg University in Springfield, Ohio.

Were you an art major?

No, I was a literature major. I was going to be a poet.

You became a visual poet.

I was drawing and painting there, until I was asked to leave.

You were expelled?

In those days, students were docile. Me and two other guys got a petition together about the food in the dining room. I told them, You know, you’ve got to sign this petition. You can’t go out there and ask every one else to sign it if we don’t sign it. One guy signed it at the end, the other guy signed it at the middle, and I signed it on the first line. The next day everyone signed it. And I was told to leave! [Laughs]

For wanting better food in the dining room?

It was a very scandalous thing. But it was OK because I had really exhausted the English department. If I’d stayed, I would have had to take political science.

How long had you been there?

I was there two years, and then I went to the University of Iowa.

Did they transfer your credits?

I got the full credits. Everything was fine. They didn’t tell anyone I was expelled. My parents never knew I was expelled. They really just asked me to leave. They told me that I’d be happier someplace else, and they’d be happier if I was someplace else.

So, I went to Iowa and I enrolled in all these classes I’d never heard about: “European Thought and Literature,” for example. It was wonderful. We read Milton. We read Nietzsche. We read Lucretius, his De Rerum Natura. My advisor said to me, You’re taking a lot of literature. You should take some electives outside your major. He handed me a catalogue. The courses were alphabetical. Accounting, no. Art, yeah. I liked art. I did that all my life. I had never thought of it as a serious thing. But I had always done it. I had always liked to sketch. I said, You mean, I could get credit? I can go in and paint paintings and get credit? Absolutely. So I did that.

So, I’m in this class. I go to a lumberyard and get Masonite cut up into different sizes. I get paints. I get all this stuff. I’m working for a few weeks furiously, I mean really turning out paintings. The professor finally gets around to me, Stuart Edie. He was friends with Kuniyoshi and many others. He’d been a Woodstock artist. He said, That’s interesting, Kipniss, let me show you something, and he picked up one of my brushes and mixed a little paint. As he reached toward my canvas, I put my hand on his wrist, and I could feel his bones, very brittle, and I had a strong grip because I was young. His eyes got wide, and he put my brush down. I whispered to him very nicely and said, still gripping, Tell me anything you want, but don’t touch my work.

Wow.

He walked on. After that he observed me for a few months without ever talking to me. A woman I was involved with said, “You know, Edie says, he thinks you’re very good.” I said, “I like to do this. I’m just having fun.”

It sounds like he was walking away from someone who was unteachable.

He was watching me. He came over to me after six weeks or two months and gave me a key to the building. He said, You’re really at this. This is something you’re really passionate about. I said, Yeah, I’m exploding in here. He told me, Do whatever you want. I’m not going to bother you. If you make progress, you’ll get an A. If you don’t, I’ll fail you. It’s either an A or an F. I said fine.

I take it you got the A.

Yeah. I didn’t like painting into tacky paint, paint that was starting to dry, and I didn’t have room to let paintings sit around and thoroughly dry, so I felt I had to finish a painting every day I went into the studio, which I did. The paintings started to mount up. You had a lot of people, who on the surface of it were serious about art, but really weren’t. They’d paint two paintings a year. How serious is that? And I was exploding. I was coming in at night. I was painting, I was writing, I was reading. There were nice young girls. I had a great time.

You had a full plate.

It was amazing. I was just discovering so many things, not just about the world but about me.

That you can certainly attribute to the art.

Yeah, oh definitely, the art and the poetry.

I had a huge anger within me. I just didn’t like the world. I didn’t like anyone.

Were you still writing?

I was writing and painting. Three graduate students come up to me, and they say, Kipniss, What are you going to do with all those paintings? Without thinking, I said, I’m going to have a one-man show in New York. What was I thinking? They looked at me like I was a lunatic, which at that moment I thought I was, and they walked away. I said to myself, What did I do? So I went to the art library, and I looked at the magazines to see what galleries were in New York. Easter was coming up and I thought I would take some paintings to New York on the school break. I saw an advertisement for a competition in a 57th Street gallery. First prize was a one-man show. I entered and came in second. Belle Krasne, the editor of Arts magazine, was one of the jurors. Joe Gans, the owner of the gallery, said, “I’d like to give you a show, too,” and I said I’d really like to have a show. So I had a show that September, which I couldn’t go to because I had gone back to Iowa after painting through the summer vacation. But I had the announcement. I put it right in the middle of the art department bulletin board. Boy, you couldn’t miss it. I had saved face. It was very nice. I had another show in another 57th Street gallery two years later, and I was off and running.

You never looked back?

Never. It was very hard after I graduated because the New York art world was in the grips of abstract expressionism. My first paintings were abstract. But the more I painted, the more the lyricism of the landscape evolved into my pictures. They became biomorphic abstractions. By the time I graduated, they were representational paintings.

From what I’ve seen you’ve concentrated mostly on the landscape.

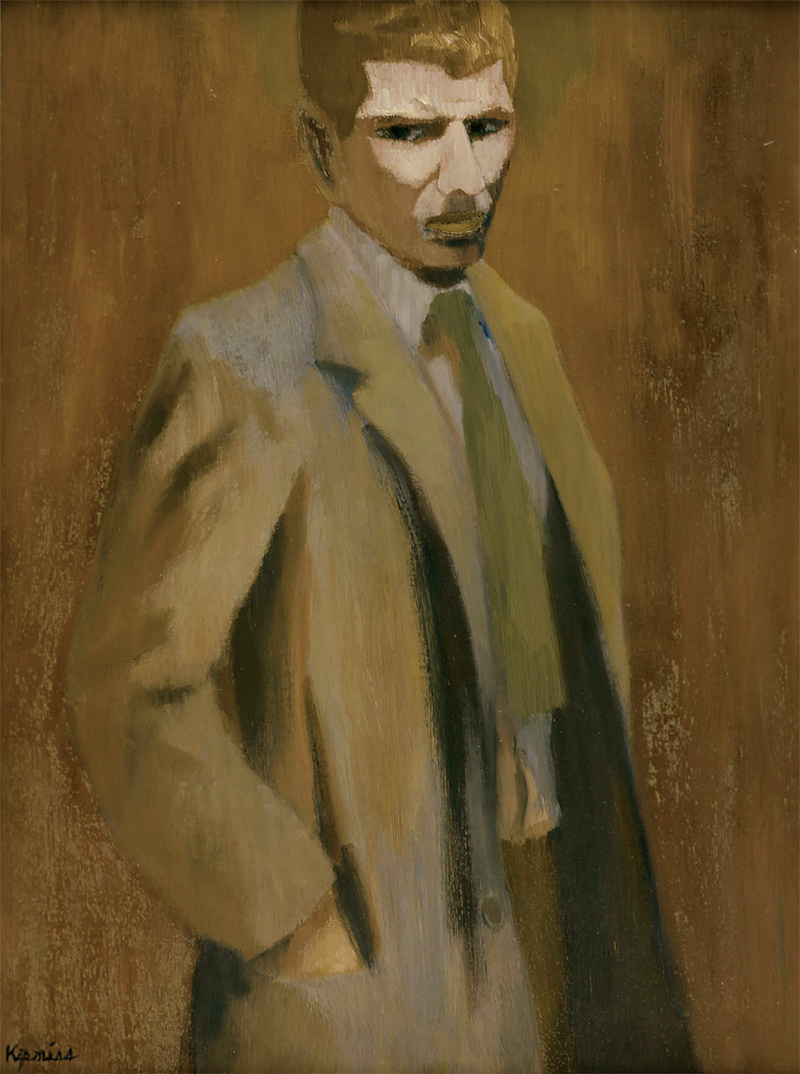

In the beginning I would paint a landscape, a still life, and a figure painting. Then I would do another landscape, another still life, and a figure painting because I thought I should do it all. The landscapes were magical for me, at least they felt that way. They gave me a great sense of life. The still lifes were okay, nice. And the figure paintings were aggressive and unpleasant. The chairman of the department at Iowa, Lester David Longman, said to me, Why do all the faces in your pictures seem to say, To Hell with you, buddy. And I said to myself, Well, to hell with you, buddy.

What does that mean?

I had a huge anger within me. I just didn’t like the world. I didn’t like anyone.

Why? It sounded like you were doing what you’d set out to do.

I was an angry young man.

Was it anger or just intensity?

Tremendous intensity, which I try not to show anymore, though I have it. I was angry. I didn’t like anything. I didn’t like anybody. I didn’t like all the institutions. I was in school because I wasn’t ready to go out and earn a living.

But you got over that fairly quickly?

No, getting over that much anger took maybe ten or twelve years. I loved studying literature. I didn’t study art. But when I graduated, the Korean War was on, and I got drafted. The draft notice said that if I was matriculating, I’d get a deferment. So I entered the art department’s graduate school, stayed there another two years, and got an MFA. Again, without instruction, but I had to take thirty hours of art history and write a history thesis.

This was still at the University of Iowa?

Yes.

What was the thesis on?

German symbolism of the nineteenth Century. I had decided to write my thesis on an artist that I hugely admired at the time, Max Beckmann. To make the project feasible, I had to deal with his antecedents, the German symbolists of the nineteenth century. I researched them: Lovis Corinth, whom I thought was a symbolist in some ways; Arnold Boeklin, and others, like Max Klinger and Casper David Freidrich. In other countries there was Walter Sickert in England and Puvis de Chavannes in France. I was putting together all this stuff, and then I came to New York for Christmas. I was planning on graduating in June. I went to the library to check out what I could on Beckmann, and I got the idea to see whether his wife was still alive. Beckmann had died maybe two or three years earlier. I found her name in the phone book and called her up. I said, Ms. Beckmann, I’m a graduate student at the University of Iowa and I’m writing a thesis on your husband. May I come to see you? She said, My dear boy, please come.

So I went to her. They lived in a brownstone, I think one of those brownstones that was later torn down to make way for Lincoln Center. She was an older, attractive woman with a yappy little Pekingese. She told me everything I wanted to know, but she didn’t talk about herself, only about Max. There was no self-importance or narcissism. She did mention she was a trained classical concert pianist.

While she was talking to me, I saw Beckmann’s paintings all around—big major paintings. The room had high ceilings with a picture molding. These were masterpieces that are now in the finest museums in the world. Above the major paintings, between the picture molding and the ceiling, all around the room, were all the famous self-portraits: the beret and the cigarette and the easel. I’m sitting there, asking questions. I was just in heaven.

So we talked for an hour and a half or two. I didn’t want to overstay. I felt I had a good in-terview. When I got up to say goodbye, she said, Would you like to see Max’s studio? I said, I would love it. She opened the door to this huge studio. There was a beautiful easel and next to it a fresh bouquet of birds of paradise flowers, which he loved to paint. She said, Those were Max’s favorites and I always have them here by the easel. I saw a fresh white canvas on the easel. All the paints and brushes laid out. She said, I’m going to come down one morning and Max will have painted a painting for me. It was so sweet. She was just adorable. It gives me chills to think of it.

When I went to the library and did some more research, I said to myself, You know, this is a huge project and I want to graduate in June. I got a lot of material on the nineteenth-century symbolists. That’s my thesis. I’ll put it together and I’ll have a thesis. I don’t want to stay here years. I’m not a scholar. I want to be a painter and a poet guy. I put the material together. I wrote it up and I graduated. It was very simple.

So what happened to the Beckmann material?

I never went into it, but it was a wonderful, unforgettable experience. Sitting in that room and seeing these great paintings in the artist’s home, just in a home, and this woman who loved him so much. She talked about him like someone she so deeply loved. Seven years later I named my first son Max.

After you graduated in June, what happened?

Then I found another reality. I was married to a lovely beautiful woman. We were happy for seven or eight years, and then she got really strange. We had children and I had to stay with her.

I wanted to get another gallery, but abstract expressionism was everywhere. And we were poor, living in a cold water flat for $24 a month at First Avenue and Ninth Street, on the south-east corner. That area is now called the East Village. Back then, it was tenements and slummy. It was mostly Italian and Polish. They were clean and nice and honest.

This was 1954. We were there until I got drafted in ‘56.

But I thought they didn’t have a draft.

They had a draft all the way through the fifties. Even though the war was over, I got drafted. I couldn’t get out of it.

I went to the galleries every six months with small paintings under my arms. I had a great M.O. I’d walk into galleries with small paintings under my arm. I wouldn’t call or send slides because slides were expensive and I had no money. No one looked at slides anyway. I would go into a gallery, never in the afternoon or on a Saturday. I’d go in the morning, 10 to 12 or 10 to 1, never when they were busy. If they were busy, I would walk out. If they weren’t too busy, I’d go in with my small paintings under my arm, and I’d ask, Would you like to look at paintings? They would say, No. And I’d put my paintings against the wall. They would see the paintings, right? No, it’s not for us, they’d say. They were very dismissive the first two or three times I went. The fourth or fifth time—and I did this every six months—they looked at the paintings, and said, They’re very interesting. They would talk to me a little bit, but no one took me on. Virginia Zabrisky came to my studio once, but I had brought my best paintings to her gallery, and I couldn’t back them up.

Was your studio the apartment?

Yeah, I had a room. I painted there. When I got out of the army, my paintings were really developing. I eventually got a very good gallery.

They sold enough to keep you afloat?

No. I was the night manager of a bookstore, and, after that, I worked nights for three years in the post office. When I left that gallery—actually, when I was asked to leave that gallery—I also, coincidentally, had to resign my job at the post office. As a nighttime worker, your name was placed at the bottom of a list of people working in the evening. When full-time day jobs came up, you either took the appointment or you resigned the evening position. You had no choice. They offered me a full-time day job in Flushing. I said, Thanks, but no thanks.

Afterwards, I went to my gallery, The Contemporaries, and I said, You know, Karl, when you’ve hung my paintings, you’ve sold them, but you haven’t hung my work in a while. It was a very good gallery on 77th and Madison, back when the galleries were on Madison. We had a sadly important disagreement, and I was out. I left very depressed.

I had no job. I had no gallery. I had little children. I had $900 in the bank. I didn’t know what was going to happen. I figured we needed $350 a month, so I had about three months in savings. I decided to look for a part-time job in the Sunday papers. In those days, you could support yourself with a part-time job. We had a little rent-controlled apartment up on 97th and Madison at that time for a hundred bucks a month.

Then I got a call from a private dealer. She said, I saw your paintings at a friend’s house, and I think I can sell them. Could I come over and look at them? And I said, Well, come to my studio. She said, I have an appointment this evening to show paintings and I think I could sell one of yours tonight. She came over and took a painting. She said, What do you want for it? I said, I need to net $350. I’m thinking, I sell a painting and get a month out of it. She sold forty paintings that year.

Wow! Who was this woman?

Muriel Werner. We became lovers. She was married and a little older. Then I went to F.A.R. Gallery. Murray Roth was working there. They were on Madison, between 64th and 65th streets. Murray loved selling my work. He said it was an important thing for him to do. He put a painting of mine in the window, facing Madison Avenue, every day for seven years. He sold between twenty-two and thirty paintings a year. Muriel was selling less because I was giving her less, but she was selling, too.

No one was asking for exclusivity?

No. F.A.R. Gallery didn’t give shows, at least not until about 1968. At that time I was one of the few living artists they showed. Later, they became a contemporary gallery, but originally they were not a gallery of contemporary art.

Were you still focusing on the landscapes?

Landscapes and still lifes. My prices were OK: $1200 or $1600 for a big painting. Five, six, seven hundred for a small painting. I was making money.

I had six really very tough years, between 1954 and 1959, then I got a good gallery. I was still struggling and didn’t make a living from my art until 1964, when I made about $4,800, which was very minimal. I only had about twelve more difficult years, but not like the previous six. From 1964 things gradually got better every year, and it seemed there was no stopping this, like I had some kind of momentum. It was just incredible. In 1968 I got a dealer in Chicago and by 1972, between New York and Chicago, I was selling almost everything I did.

How did your expression evolve from that period of struggle?

There was a lot of evolution. I’ve been through many, many periods. Always landscapes. Art isn’t about the subject matter. It’s about …

The subject is art.

The subject is the artist. The subject is the heart and soul of the artist. It’s like a poet writing a poem about a rose. It’s not about a rose; it’s about life and death.

Can you discuss that process?

Let me discuss something else first, and then I’ll get to that.

My early paintings were abstract. Then they were biomorphic, semi-abstract, then they were gradually more representational. I had a show at the Contemporaries, the first show there, sold seventeen paintings, which isn’t what you think it is because my net was only $2400. It was something of a success, but, I didn’t like the people who were buying my paintings. There was something missing. My paintings were very lyrical, you know, bright greens, bright reds, very colorful landscapes. The people who bought them treated them like decorations. It really agitated and disappointed me. I remember a Ms. Applebaum said to me, Mr. Kipniss, I really would like this, this is my favorite, and I would like one just like it, but in grey with pumpkin highlights. I went home, and even though I was making money, I said, This isn’t what I want. I know there are other things within me. Let me go deeper into myself. So I started painting from this reservoir of anger that I had.

Animosity?

Animosity, disenchantment, estrangement.

I can understand Ms. Applebaum aggravating you, but …

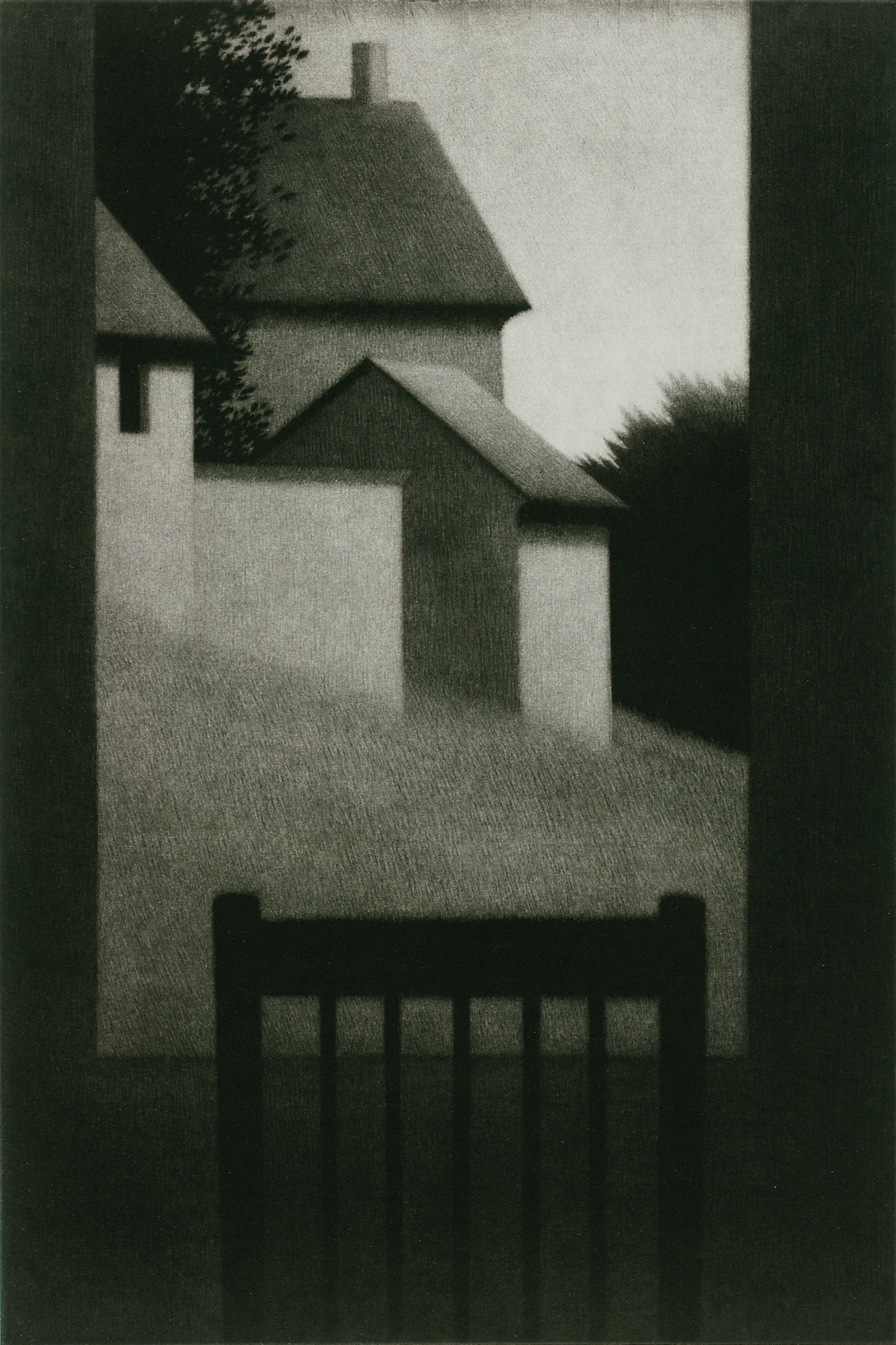

One person brought back a painting because their eleven-year-old niece said, The houses have no windows. They said, We can’t have a picture with houses with no windows. There was something shallow about the whole experience. I started painting dark paintings. I did sketches at Central Park, near where I was living. I was doing these fabulous trees, fences, and even views through the park of traffic on Fifth Avenue. Now I was really painting strong paintings. I felt wonderful. This was it. This was what I needed. And I had another show in 1961 at the Contemporaries, but there was a blizzard. We made the same money as the first show, because my prices were higher, but we sold only seven paintings. I knew they weren’t going to give me another show. But my paintings were getting richer, filled with my deepest emotions. I wasn’t just painting pictures now; I was really getting at something. Of course, it was this, I think, that led to the success that I’ve had. It was just very nice. Over the years, things changed. I evolved. In 1967 I got into printmaking at the suggestion of Murray Roth. I fell in love with printmaking.

When I had gone to work in the post office, I stopped writing. I didn’t have time to work in the post office, write, and paint. Up until then, I wrote and painted equally. So, I said, when I get older, I’ll write, which I’m doing now. I’ve written a lot of essays.

You were going to talk about how, whatever the subject matter, the artist is talking about himself.

In 1961, I started to get closer to myself. I started finding that painting wasn’t just about making pictures. I realized you could really learn something about yourself.

You had this awareness at that time?

Hugely, much more than ever before. I started looking differently at the paintings of other artists. It became almost excruciating because sometimes I’d go to the museum to look at a painting and get teary.

Were you talking to other artists?

No. I didn’t get to know other artists until I was in my sixties.

I haven’t heard you mention other people.

I knew one guy, Bill Klutz, who I went to school with, who is a good painter. He was a wonderful painter. I also knew him when he came to New York.

Did you bounce ideas off other people?

I knew one couple, who lived across the street from us for a year, that I met while in the army. They both studied with Hans Hofmann. The husband once told me, he said, You’re never going to get a show painting landscapes. Why don’t you look around you and see what’s happening. A year later, when I got the show, and I told him that I got a show, that son of a bitch said, Well, of course you got a show, you paint those nice little landscapes.

Were you consistently married?

My wife and I separated in 1963, but the doctors told me that I couldn’t leave the children with her, and that she might be in and out of institutions. We stayed together until 1982. We had been married twenty-eight years.

Did you share your awareness of art with anyone?

I almost never talked about art. I hardly talked to anybody. I was never part of any community. I was never a part of anything. I didn’t like people who talked about art. I said, Go do it.

This sounds like part of the anger.

Absolutely.

How, then, did you develop?

Since I started painting in Iowa, even through the army, even through whatever, I did a full day’s work every day. I lived off the post. I had an apartment in town, I painted every evening. I had Wednesday afternoons off, Friday afternoons off, and Saturday and Sunday. I painted as much as I could. And I’ve always done that. I’ve always felt that you learn from doing. And I was obsessed.

I think the best you can do is give an artist a place to work, and then he should find his own education. He should work and he should paint. And he learns from painting. You’re probably not going to want to put that in because it’s so anti-school.

Why wouldn’t I want to put that in?

Well, I don’t think you learn from being taught. I don’t think teaching is good for an artist, but a lot of artists think they need to teach because that’s how most make a living. I would never do that. I don’t think it’s good for an artist. I’m going to tell you why. When you teach, you have to have something to teach, something that is set that you can tell the students about. You can’t teach them about something that’s still in motion and undecided or unsettled. I don’t know what I’m going to do tomorrow. I’m working every day, but I don’t know what I’m going to do. My work is constantly evolving. My belief is that, if I start teaching, I’ll start painting the same painting every day.

I also think it’s important to make mistakes, to recognize a painting situation your skills aren’t up to dealing with, and find a way to invent a solution that’s yours, your way of painting, like your way of seeing. And not just for a young artist, but all your life.

From what I’ve seen, you are very close to your subject matter. Some subtle changes took place over time and those landscapes have gotten deeper.

You have no idea. If you would see blocks of my work over the years, say, every two or three years, it looks like the same artist but a whole new period. Right now my work is very lyrical. But I think I’m going back to the dark, which I’m attracted to. I struggle with every painting I make.

Still?

Yeah, because every time I paint, I’m trying to do something I haven’t done. I don’t paint the same painting. If people aren’t familiar with my work, they’ll say, Oh, Kipniss, trees and houses. But often people who are into my work say they can’t buy just one painting because there is no quintessential Kipniss painting. So many things I do keep changing and evolving; people who like my work tend to have a few.

Through the vehicle of, let’s say, houses and trees, you can go further and further into your …

It can take you any place. It’s just amazing. In the act of painting, you find more parts of yourself, if you don’t try to use the same solutions over and over, and if you are looking for new ways to resolve things, to learn, to get into the canvas. Once I start working on a canvas, it’s no longer a two-dimensional surface. I’m in that space and I’m creating a space. I’m creating this world. I’m putting the furniture in that world that’s in my head that day.

Do you spend the same amount of time printmaking as you do painting?

No, I paint Monday through Friday, and I work on my copperplates Saturday and Sunday.

Do you ever take a vacation? Robert Kipniss interview

Yeah, I take time off, but I don’t go away much. I’ve taken a few trips. We went to Holland and Belgium three years ago. Two years ago we went to Provence and Paris during the fall. But we only go for eight or nine days. That’s my limit.

Which artists make you cry?

Cézanne. The good Cézanne. There are all kinds of Cézanne. The way he puts the paint on the canvas, and the way that space evolves! And George Bellows, Winslow Homer.

Any Old Masters?

Well, the etchings of Rembrandt.

More than the paintings?

Yes, much more than the paintings. I like the paintings, but the etchings are unbelievable. But he doesn’t get to me the way Cézanne and Degas do.

Is there a direct correlation between looking at and being moved by Cézanne and your own work?

I can’t work like him; I can’t paint like him. I have no idea how he did what he did. He amazes me.

I’m not saying like him. The question is, when, in solving problems, in delving into going further, there’s no ….

I can’t think of that. I’m busy working.

And that’s always been? Robert Kipniss interview

Yeah.

Yours is a unique story.

Self-taught. Self-involved. I really worked at it.

What’s your sense of how art itself has evolved or devolved?

I feel very estranged from the art world. I think it’s amazing that I’ve had a career. Next year will be sixty years since my first one man show. For the last forty-five or fifty years, I’ve had shows all over the world, constantly showing and selling. It’s very nice, especially since I don’t think I’m really a part of the art world. Until a few years ago I had a wonderful dealer here in New York City, Beadleston Gallery. Since he closed I haven’t had a painting dealer in New York, and given the gallery situation I’m not sure if there is a purpose in finding one. I have a really impressive dealer in San Francisco—Rowland Weinstein. He’s a prince. And I have the Old Print Shop in New York City, and others in many cities.

I don’t want to look for a painting dealer. I don’t want to go to Chelsea. I don’t like Chelsea. I don’t like SoHo, although I had a show at the OK Harris Gallery, which was nice.

When I showed at the Contemporaries, and then at F.A.R. Gallery, I felt like I was a little bit in the swim. Then I went to Hirschl and Adler, had two shows there, and stayed with them five years.

It’s been a long time since I have cared about feeling connected with the art world. I don’t like what’s going on. Performance art, installation, conceptual art. I go to the Whitney biennials, and I feel there is no reason for me to go in there.

Do they own your work? Robert Kipniss interview

Yeah.

Do they ever show it?

I was in a recent acquisition show in 1972. They have about twelve of my prints.

Which other museums own your work?

A lot of them, except the MoMA. There might be an exception here and there. I’m in the Pinakothek der Moderne. I’m in the Victoria and Albert. The British Museum has sixty pieces. I’m in the Met.

It’s funny that there is this isolation.

That’s the word: isolated.

But you seem to enjoy it. Robert Kipniss interview

I like it; it’s fine. There is no pressure on me. I can do whatever I want. I can paint however I want. There are always galleries that want to show my work. And they sell it. I don’t have a studio full of paintings, and I’ve painted about three thousand paintings.

You’re probably the most unusual of all the people that I’ve spoken to about this. An artist having had an extraordinarily successful career by choosing to live outside the mainstream. It’s not an easy path. Yet all of your choices seem to have been all the right ones.

I’m convinced the reason I’ve been successful is because I really paint something from so deep within me. I’m in so much contact with the deepest part of myself that I touch that part of me that is within everyone. Looking at the more superficial parts of our personalities, we are all very different; but the deeper you go, the more similar we are. And I try to paint from there. It seems that when people stop and look at what I do they want to have it to live with it, and I’ve sold lots of prints. I’ve sold 84,000 mezzotints, dry-points, and lithographs.

Seriously, 84,000?

I’ve sold 84,000 prints. I’ve done over 600 editions. As I said, I love to work.

Do you ever give advice to young artists? Or do you have young people visiting your studio?

No, but I’ve gotten letters. I went out to Wittenberg University to give a talk to the art majors in April 2010.

It just sounds as though it’s been relatively simple for you to arrive at this way of living and working. You’ve arrived at a formula, but that’s not quite the right word.

No formula. It came from the heart, and people have seen that and they relate to it. I knew how I wanted to live my life, and I just went at it straight ahead.

Do you feel you have a special gift for delving into this material, or does it just come out of this intense doing of it?

I think both. It’s lucky. I can hypothesize, but I don’t really understand why people like my work, but they do. I have a good friend who says, You paint weird pictures, and you paint dark pictures. No, I paint light pictures, but he says, You paint so many dark paintings, and you make very dark prints, and nobody likes dark, and they buy your pictures.

I love to look at the print you gave me of the two people in copulation.

Isn’t that wonderful? It’s like a little sculpture. It’s called Valentines.

You seem to have cut through the verbal crap of today’s art world. There’s so much explaining because people feel misunderstood. I think artists, especially young artists today, try to exploit the misunderstood genius image.

Paintings are not about words. They are pictorial statements. I believe in making a statement, but it’s a pictorial, not a verbal, statement. But people need words, so you have the critics. The critics have let the artist down because they’ve seemed to become more important than the artist, as if they have the power to decide what art is or define what the new wave will be.

I wouldn’t suggest you attend a College Art Association meeting.

I went a long time ago, a couple times. It’s terrible.

It is terrible because they can’t relate to artists. Artists are just a bunch of Neanderthals who should be in their cage, making their paintings, throwing them out through the cage, and letting them explain it.

I got their message: art is from the past and what they understand is iconography. As my grand-mother would say, They should live and be well.

But they don’t even understand that. They decide what it is. It is more important for them to come up with an original concept, which is what academia demands, because you can’t just talk about art and why is it art. There’s got to be a raison d’être that no one else thought up before.

They are inventing the art and the artist makes it. But the thing is, when you look at something, when you really look, not when you are with someone else, not when you are walking in the country with a friend or a lover or whatever, but when you’re alone and can really just look at something to try to understand what your feelings are about what you’re seeing. Seeing provokes feelings, if you are open to feeling something. But you have to be open. You can sit alone and you can look at pipes and you can look at walls and you could look at whatever. You feel something about space, you feel something about shadows. You feel something. And that’s what I paint. And there are layers to feelings.

There is also structure to art, which, I think, permits those feelings to be expressed more strongly. There is composition. There is color. There is concept. Robert Kipniss interview

There is the formal aspect that puts it all together.

Do you think that the ability to connect, as you have, is being impeded by technology, information, and a lack of articulation?

Number one, most artists are not trying to connect. They want to be admired. They don’t want to be understood. They want to be worshipped. They want to be rich. They want to be stars. This has nothing to do with making art. It has nothing to do with communicating. It has nothing to do with developing something to communicate, or delving into yourself, digging and finding. You have a statement to make about life. To me, every painting is life and death. I don’t mean it is life and death to do it. It’s about life and death. The subject is reaching beyond your mortality. The subject is getting to something that is, hopefully, of value, of something that won’t disappear. I don’t mean that the painting won’t disappear. But the quality that you are looking for in painting is about something that is forever and you’re reaching for it. When I look at a work of art, I want to be able to see why it was made. I can look at a Degas and I think I can understand why he did the painting. There is so much to learn from every painting he did. I can’t codify it, I can’t put it into a pigeonhole. But there is a lot there. I can see, I can feel so many reasons why that painting is there.

Would you call it self-evident? Robert Kipniss interview

It depends on how much you can see, and how much you let yourself feel. Painting today is not about that.

Are the conditions under which we live today less supportive of artists who might otherwise have been inclined to plumb the depths as you have?

There will always be people who prefer to feel, to think, to experience, and grow. It’s not up to society to make artists comfortable.

You know, the real public, if you look at people who go to shows, the big shows at the Met, you see people really looking at paintings. You see people really looking, feeling, thinking about it. These may not be the people who have a strong voice, but there are many of them.

This interview was originally published in the Spring 2011 print issue of LINEA.