[1]

[1]At the top of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s grand staircase off to the left is a passageway gallery that contains a rotating exhibition of drawings and prints. Many people hurry past these small precious works of art without a glance on their way to a blockbuster painting exhibition at the other side of the building. But I always stop and look at the drawings in wonder.

Drawings reproduced in books or viewed on a computer screen can never come close to what it is like to see the real work. It is difficult to judge the relative size, color, and range of values unless the work is viewed in person. The nuance of line and the texture of the surface cannot really be sensed and felt.

Five drawings recently on view at the Metropolitan Museum took my breath away. Looking at these drawings I am able to travel back in time to communicate with artists living centuries ago, and I can ask them, How did you do that? Why did you do that? Their answers are there in the work, if only I take the time to really see and understand them.

I frequently visit the museum in search of finding answers to problems I am having in my own work. After unsuccessfully fighting to get the back eye of a three-quarter view portrait correct, I went to the Metropolitan Museum in search of help. I found that help in Portrait of a Young Man by Wilhelm von Kügelgen, a mid-nineteenth century German artist.

[2]

[2]By taking the time to describe in words what I was actually seeing, I gained some valuable insights into how I could do it better myself.

I noted how von Kügelgen solved the problem of the troublesome back eye by first using a carefully observed line to indicate the edge of that side of the face. His line emerges crisply from behind the young man’s wispy hair. It is ever so slightly softened and lightened and then hardened again as it descends down the round shape of the forehead to become a smidgen sharper. Yet it slides over the bony brow ridge disappearing for a tiny bit behind the hairs of the eyebrow. Continuing further on its path, the line clearly defines the side of the eye socket ridge that keeps the eye tucked safely under its structure. Emerging from under the ledge of the eye socket, another mark suggests that the upper lid is a little larger than the eye, just big enough to blink over the round eyeball but snug enough to hold the eye in place. There is a tiny black chalk stroke, easy to miss, but crucial to the anatomical sense of the drawing, just to the left of the iris that shows the upper eye lid continuing beyond the lower lid as the two join together to hold the eye as it moves focusing here or there.

[3]

[3]The upper lid covers a bit of the top part of the iris and the lower a little less. Although the lashes of the upper lid, the lid ledge itself, and the upper part of the eyeball are in shadow, the thinner lower lid faces up and catches light. The iris and the pupil are not exactly target-shaped circles but are slightly narrower ovals tilted back and downward.

By carefully observing what I was actually seeing in von Kügelgen’s drawing and describing it to myself, I was able to understand some of the specific techniques he used to deal with the difficult job of convincingly rendering that eye. Although he accomplished that feat with carefully rendered lines and a delicately restrained use of black and white chalk, I began to feel more confident about using what I had learned from him in my own work in my own way.

I often think about drawing as painting with a pencil. The perceptive curators placed five very different approaches to drawing near each other, likely to raise some questions about the nature of a beautifully-rendered or painterly-drawn image.

[4]

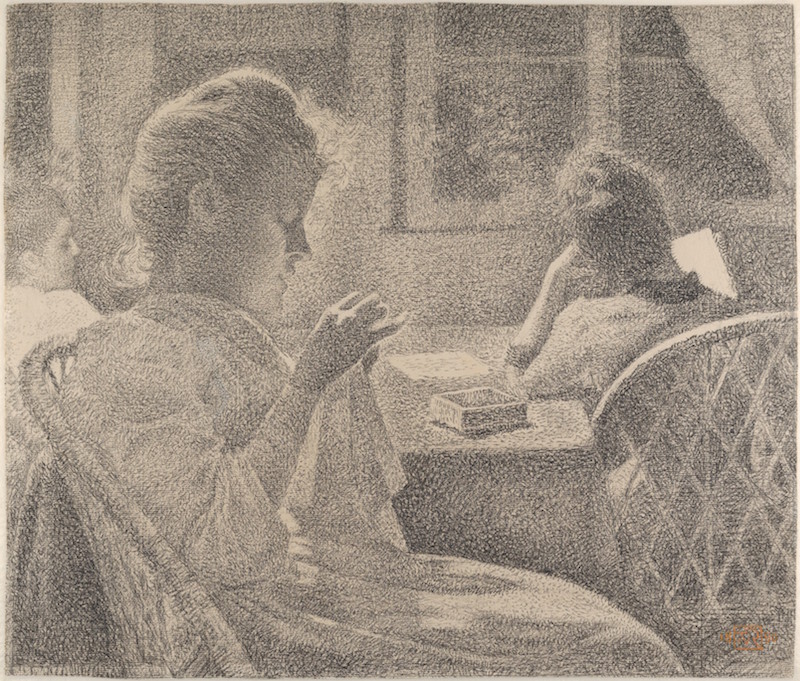

[4]The intensely dark Embroidery, The Artist’s Mother, rendered by George Seurat with Conté crayon, a square stick of ground graphite combined with charcoal, posed the question of how dark and totally tonal an artist could go and still make an image discernible to the human eye. Artist Paul Signac wrote that works on paper like this one were “the most beautiful painter’s drawings that ever existed.”

Seurat’s drawings have always fascinated me. No line. All tone. Painterly. When I find an artist whose concepts about drawing are akin to my own inclinations, the experience supports my convictions and gives me the reassurance and the courage to push further in that direction in my own way.

In Intimacy, Theo Van Rysselberghe used a technique similar to Seurat’s in Embroidery, The Artist’s Mother. Both images picture a woman engaged in the female task of needlework. In contrast to Seurat’s dark image, Van Rysselberghe explored as light as possible a range of values to create a feeling of luminosity within a complex composition of forms. Both artists placed one value against another to achieve their goals. Neither resorted to the use of much or any line.

On the other hand, line was the dominant choice of expression of Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres in his Portrait on Madame Paul Meurice, nee Palmyre Granger. The centered visage’s almost symmetrical features, the simply-stated sinuous, graphite line is elegant and perfect to express the quiet grace of this gentle young woman.

The off-center placement and the dramatic horizontal slashing lines of Käthe Kollwitz’s Self-Portrait, Turned Slightly to the Left tells a completely different story from all of these other portraits in style and intent. In von Kügelgen’s portrait, the young boy’s eyes look shyly down away. Käthe Kollwitz’s eyes look straight ahead directly at us. Both artists use totally different styles of drawing, but both reveal the same intense knowledge of the anatomy of the eye.

[5]

[5]The drawing and print gallery at the Metropolitan Museum of Art offers a rotating exhibition of some of the best work to be enjoyed and studied. Why not take the time to look?

- [Image]: https://asllinea.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/DP827290.jpg

- [Image]: https://asllinea.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/DP808124.jpg

- [Image]: https://asllinea.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/DP845007.jpg

- [Image]: https://asllinea.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/DP854855.jpg

- [Image]: https://asllinea.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/DP810279.jpg