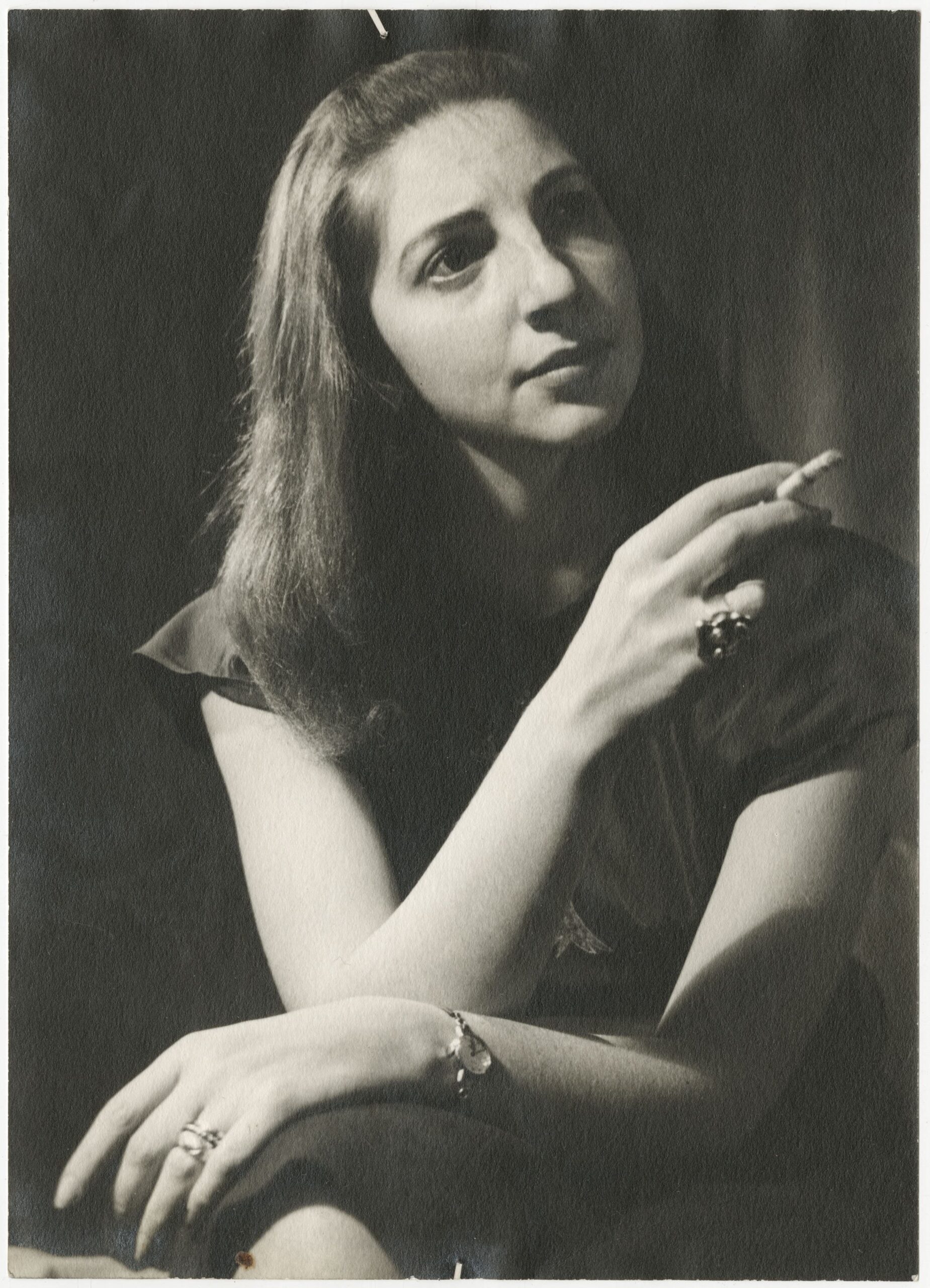

B.Z. Sacks, my mother, owned a gallery in the subway arcade at 42nd Street and Sixth Avenue in 1949. It was called the Tribune Subway Gallery. She was twenty-five years old.

[1]

[1]Taking classes at the Art Students League in the late forties, Bernice was part of community whose creed was that art was at the center of life, in drawing, music, dance, drama, literature, all the arts. When the opportunity presented itself, she went to her father, a Russian Jewish peasant, who, from pushcart to trucking, was building a business bringing fresh produce from upstate New York to Manhattan, and asked him for the money to support a gallery. One can only imagine his incredulity. She needed four hundred dollars immediately. Why? Because the current director and founder, a German Jewish émigré, and dear friend, had to leave the country, and she was the only one who could take it over, because, after all, she had been there since the beginning. My grandfather, known throughout my life for his thrift, gave her the money, as letters attest, and the gallery, whose raison d’etre was to support artists on a “strictly non-profit” basis, would continue its mission, there, underground, at the back of a bookstore, in the subway arcade.

In 1949 the subway cost ten cents and 10,000 people a day passed by the gallery. The location was then known as the “crossroads of the world.” Jack Dempsey’s, one of the most famous restaurants in the world, and the Astor Hotel, one the most luxurious, were only a few blocks away from this bustling location. Just below the Schulte Cigar Store on 42nd Street, a well-known national chain, and sandwiched between a barber shop and a jewelry store, was the Tribune International Book and Art Center. The Tribune Subway Gallery itself was a windowless room at the back of the bookstore. Its stated goal: to bring art to the people. Opening its door shortly after V.E. Day, May 8, 1945, committed to social realism, welcoming unknown artists from the world over, the gallery stayed opened from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. daily, even staying open past 10 p.m., bringing art to the people. Exhibitions generally lasted two months and openings were also occasions which brought people together to discuss both art and politics.

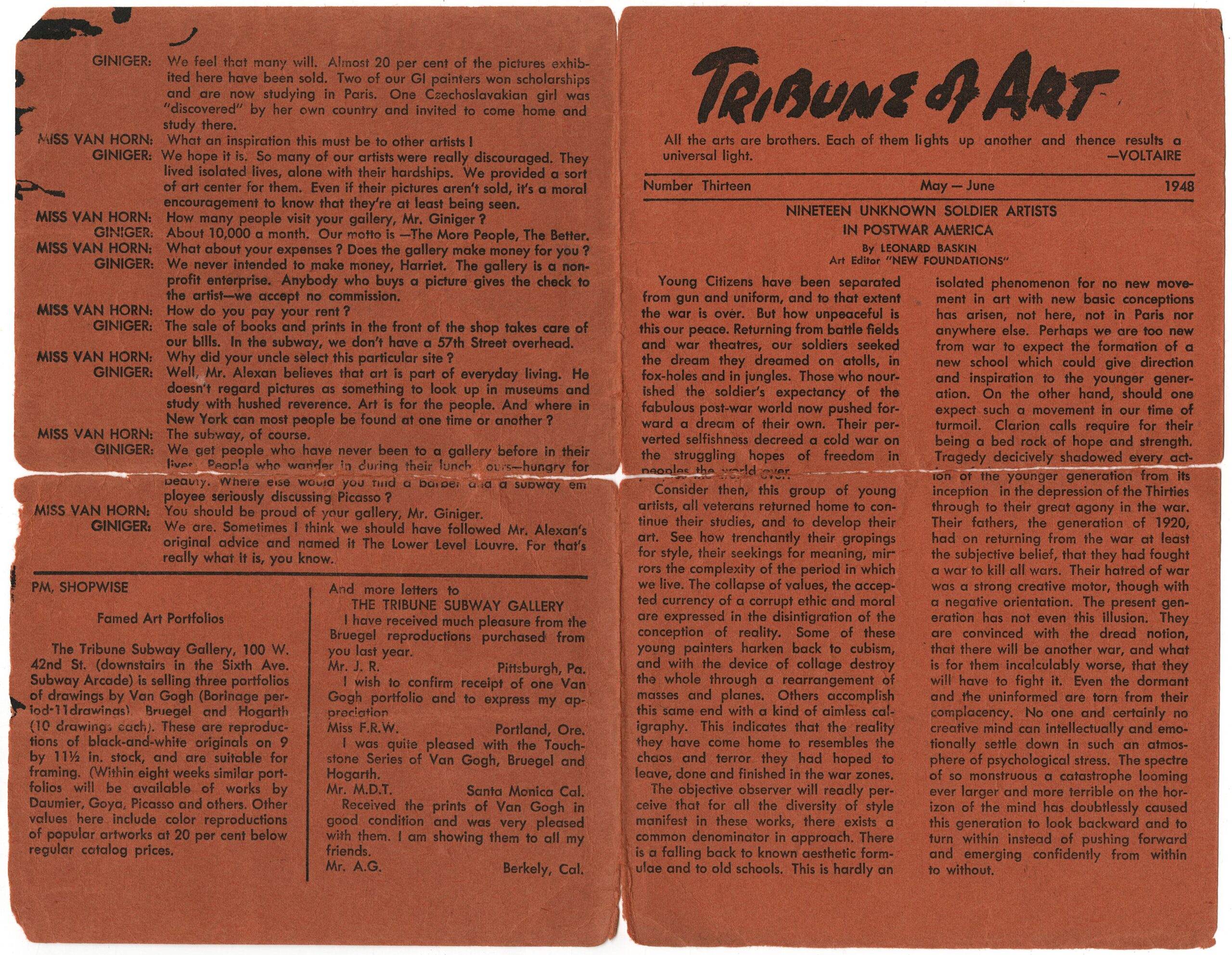

The gallery’s first five exhibitions centered on World War Two. One focused on “soldier artists,” returning G.I.s who took up the pencil and drew what they had lived in Europe. At a time when the country was extremely hostile to the Japanese, the gallery presented fifteen post-war Japanese artists, modernists, including early work by Ichiro Fukuzawa[2]. Alongside the showing of unknown American artists, the gallery featured the works, originals and reproductions, by German expressionists, regularly showing Ernst Barlach, Max Bechman, George Grosz, Max Pechstein, Miriam Sommerburg, Käthe Kollwitz, Rudolph Jacobi, and others. Artists from Haiti, Mexico, China, as well as graphic artists, Leonard Baskin, Antonio Frasconi, Irving Amen, among many others, all found their way onto the walls of the Tribune Subway Gallery.

Far from the well-known galleries on 57th Street, then the center of the art world in New York, the gallery’s exhibitions received no less than thirty notices in the New York Times between 1945 and 1954, alongside reviews of Knoedler, Janis, Galerie St. Etienne, the Museum of Modern Art, the National Academy of Design, among others. The reviews were consistently favorable. Art critic, Howard Devree, routinely highlighted Tribune exhibitions in his column. In July 1947, he announced:

An exhibition entitled ‘‘Eight Artists of the People” fills to capacity the small “Subway Gallery” of the Tribune Book and Art Center, at the southwest corner of Forty-second Street and Avenue of the Americas. Only director Alexan can tell how he crowded so many things into this space. Here are timeless cartoons by Daumier; prints by Hogarth, examples of “Disasters of War’ by Goya; bitter memories of the recent war by the overpowering Frans Masereal; several of the always moving and tenderly human lithographs by the late Käthe Kollwitz; lesser-known examples of Breugel’s graphic work; fine reproductions of drawings by Van Gogh (from the Bordrecht Museum) and finally, one or two Picasso items.

[3]

[3]Refusing to take any profit from the sale of original art, and giving all the proceeds to the artists, the gallery survived by selling reproductions that Georg Friedrich Alexan, the founder and director of the gallery, was able to obtain from French, Swiss, and German publishers. Each exhibition was accompanied by a brochure that offered an essay on the show, commentaries on the gallery from various publications, as well as notes from Alexan, one of which decried that American publications were inferior and never got the colors right. Alexan was also the founder in 1945 of Touchstone Press which produced superior black and white reproductions of drawings by well-known artists, which were always accompanied by passionate essays. It was as a writer that my mother first got to know Alexan.

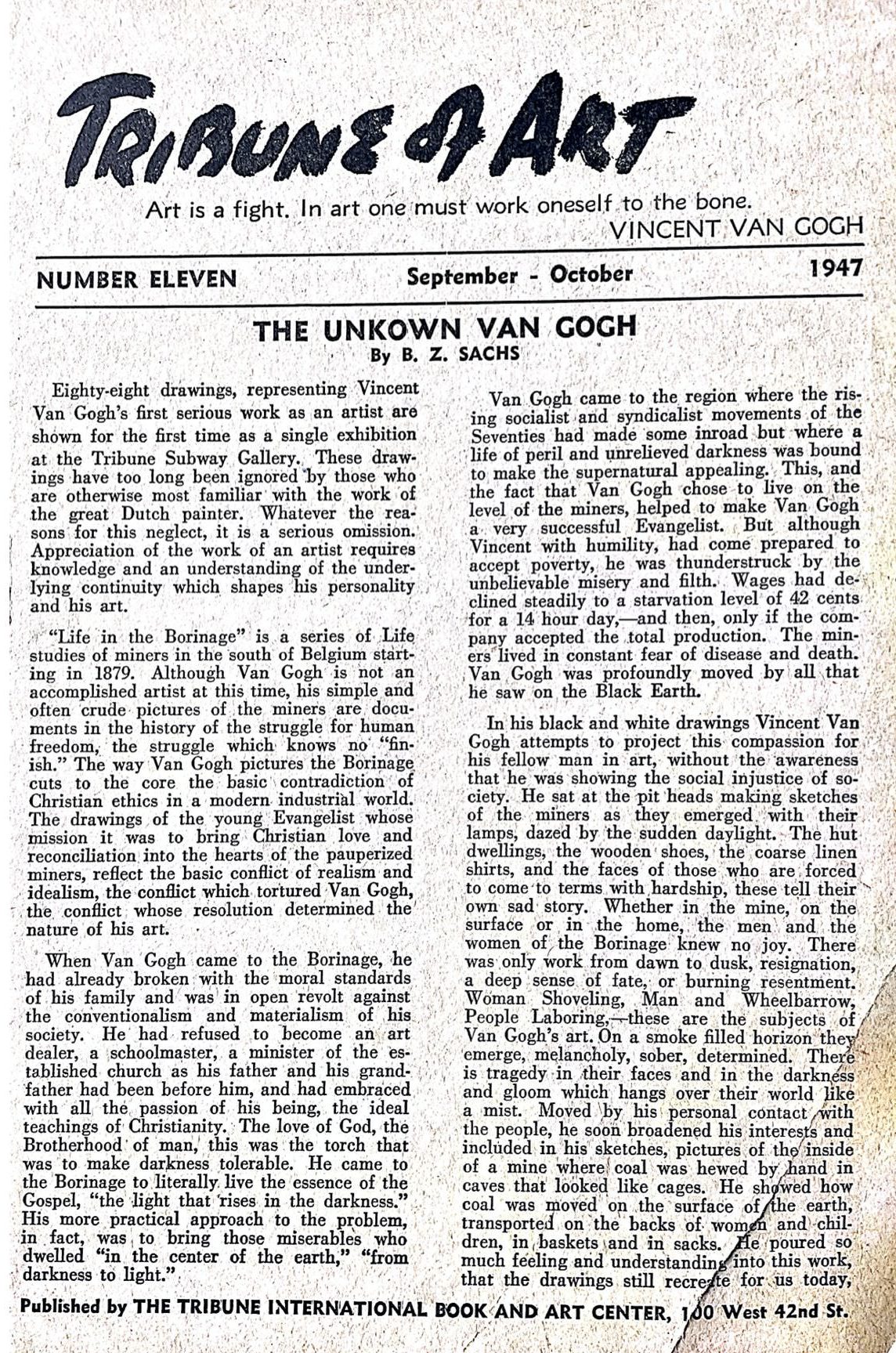

Between 1945 and 1949, using her own name, B.Z. Sacks, she wrote essays for the “Tribune of Art,” the brochure that accompanied each exhibition. These pamphlets also contained snippets of art reviews in praise of Tribune exhibitions, as well as letters to the editor, often from well-known artists or prominent people, along with promotional material. This material was clearly meant for the subway traveler who stopped as well as for the culturally and politically well-informed. These documents are the primary physical evidence that the gallery existed, especially since the arcade has since been sealed. Bernice also wrote commentaries that accompanied the reproductions Tribune Subway Gallery published by Touchstone Press. Arguing that van Gogh’s first serious work as an artist had been ignored by the art establishment, the gallery hosted what it claimed was the first exhibition of his drawings of miners from the Borinage. Bernice wrote:

Although Van Gogh is not an accomplished artist at this time his simple and often crude pictures of the miners are documents in the history of the struggle for human freedom, the struggle which knows no finish. …The drawings of the young Evangelist whose mission it was to bring Christian love and reconciliation into the hearts of the pauperized miners, reflect the basic conflict of realism and idealism, that was at the center of his art.

A recent graduate of the University of Wisconsin at Madison, Bernice had been writing art reviews since college and had already been writing for several left-wing presses—New Masses, then Masses and the Mainstream, Partisan Review, and others, sharing a pseudonym with several close friends, including Milton W. Brown, known to his friends as Mainey, and Morris Dorsky, known as Moishe. Mainey would become a world-famous art historian, author of American Painting from the Armory Show to the Depression[4] (1955); and Moishe, a beloved art professor, followed Mainey as Chairman of the Department of Art at Brooklyn College. These were the friendships of a lifetime. I know this, not just from factual records, but because we all lived on the same block for the first forty years of my life.

[5]

[5]All three households resided on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. I was a classic “red diaper baby,” bombarded by all of them with lectures on Marx, Freud, and the dominating importance of culture from infancy onwards by these ever wonderful, irascible, and knowledgeable people. This was especially poignant for each of us because they were childhood friends of my father’s, and he was to die when I was ten years old. My father, Raymond Sacks, was a Naval Communications Officer sent to Japan in October of 1945, two months after the atomic explosion in Hiroshima. He was stationed in Matsuyama, near the site of the explosion; exposed to radiation, his suffering would begin upon his return to New York at the end of 1946. Bouts of illness and remission would haunt the rest of his life. Mainey and Moishe, their wives, Blanche, art historian and scholar’s scholar, and Marsha, adored him and their love for him, as well as for my mother, lead them to look after me, to become my leading lights, including me in their discussions of momentous topics throughout the decades.

[6]

[6]It was this community of friendships and love that created art, studied it, wrote about art, argued about it and collected it. Art and sculpture were everywhere. A table expressed a point of view. In our home, the long entrance hallway was lined with Leonard Baskin’s prophets, including the imposing woodcut of a crucified eagle. Nearby, colorful, primitive paintings of Mexican families. Drawings by Kollwitz, Odets, Picasso, objects collected from travels, and books and prints from the Tribune Subway Gallery. Many others, some who would go on to have blue chip reputations, others not. Perhaps, the only abstract painter that ever had a showing at the Tribune was Savo Rudulovic.

[7]

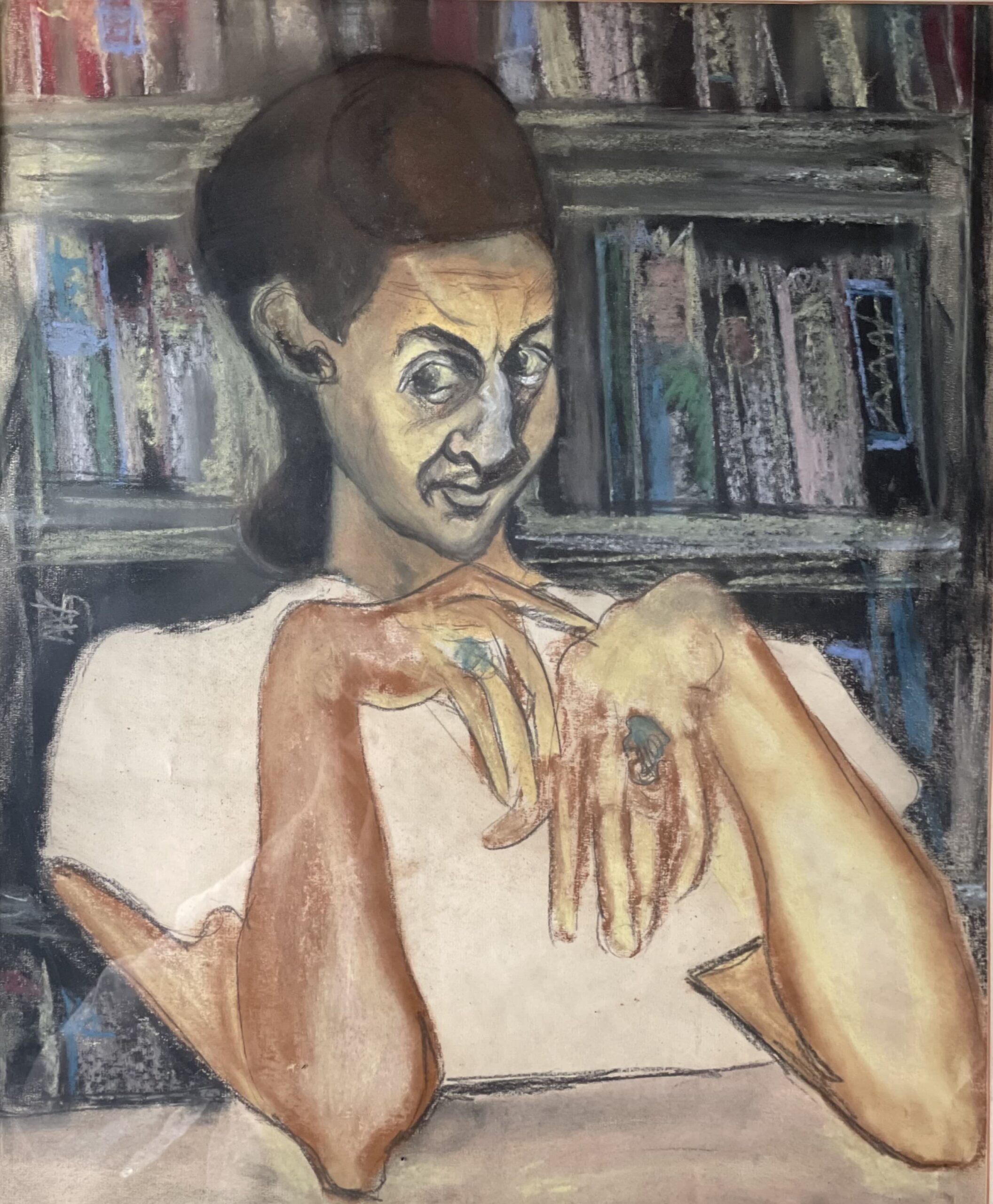

[7]Smack in the center of the dining room, looming over the dining table was Bernice’s self-portrait. Painted at the League in the late forties it captures a forceful woman with an amused and ironic expression, is she approving or disapproving of what she sees? Striking because there is no attempt at sentimental beauty other than the graceful hands folded in front. Is this how she saw herself then? The woman and mother I knew, years later, was vain, and craved attention, so it was incongruous that she displayed herself, as this young and demanding, somewhat unattractive woman, right in the heart of the apartment. No one ever talked about it, as it was baffling. She rarely talked about herself in those early formative years, before her husband died, and before the menace of McCarthyism. This gaze, and this silence, right there in the center, would go unchallenged. Fear, sadness, and perhaps, deepest of all, her romanticism, guarded the intimacy of those years when love and idealism first flourished. The portrait hangs on a wall in my home now, beneath a Chinese rubbing given to me by Mainey and Blanche and near a Kollwitz self-portrait, a drawing from a collection of lithographs from The Tribune Subway Gallery.

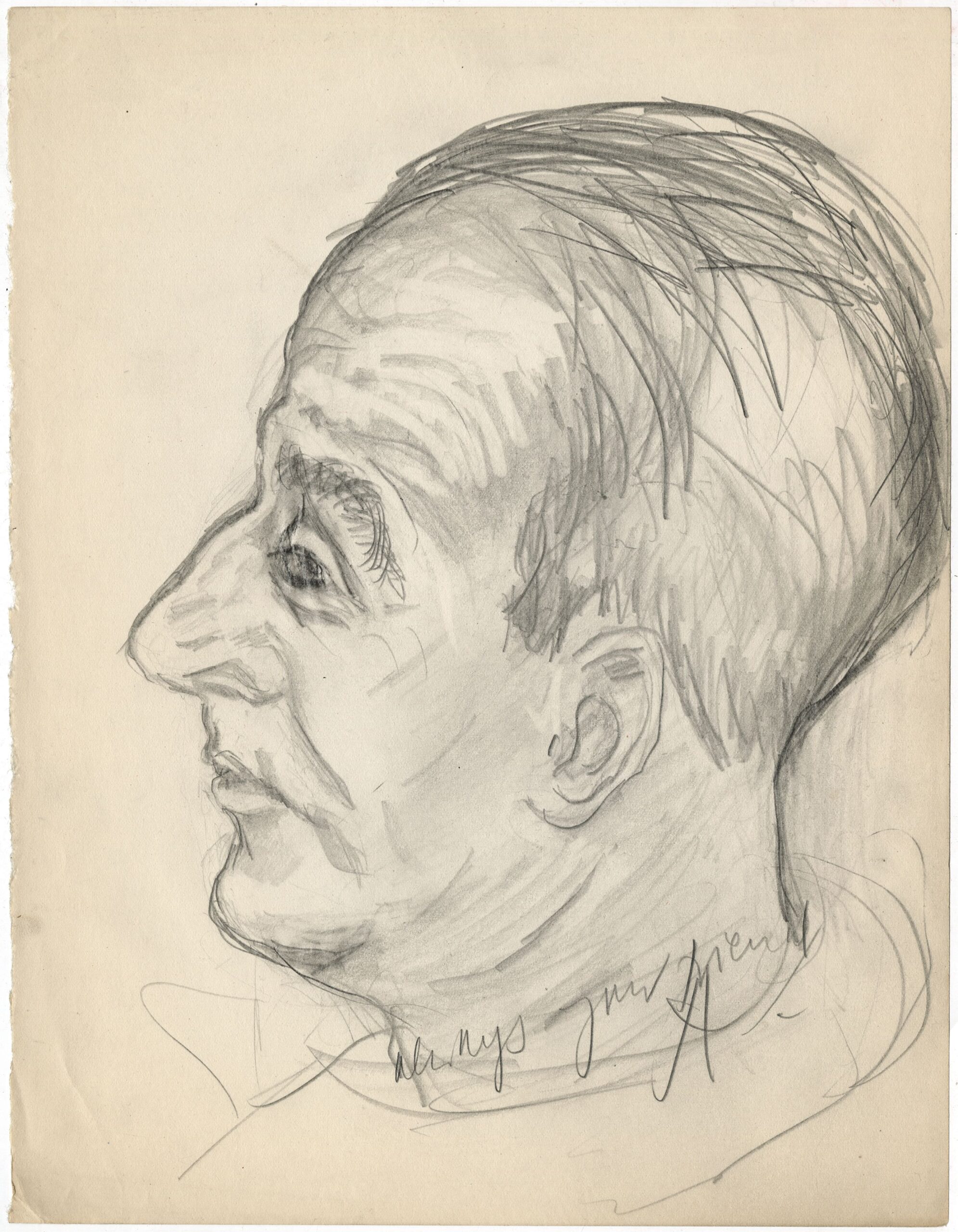

Photographs from 1947 and 1948 reveal gatherings of smoking, drinking, finger-pointing intellectuals, in rooms lined with books and art. In one, Alexan can be seen elegantly dressed, sitting in front of a De Hirsch Margules painted chest at a birthday party for my mother in 1947. At the same party, there is a photo of him with his arm draped over the composer and fellow German émigre, Stefan Volpe. Volpe, taught music to my mother’s closest friend, Shulamith Chernoff, teacher and poet, whose father taught at the Jewish Theological Seminary. In this network, within circles of friendships and passions, Alexan and Bernice’s paths crossed. A 1948 sketch of Alexan by Bernice has the words “always your friend, A.” And yet, once he left, turning the Tribune over to her, he vanished from her life entirely. It’s not hard to see why. It was the height of the McCarthy hearings, the Cold War was escalating, and he was a known Communist. Alexan was born Alexander Kupferman in Mannheim, Germany, managing to escape the holocaust and arrive in New York in 1940 at the age of 39. He lived in Washington Heights, married, and the couple had a child in 1942. He was more than twenty years older than my mother. As my mother would tell it over and over through the years, “He had to flee. He left with Eisler on the last boat.” Left with Eisler. Fleeing! With his seven-year-old daughter. What did that mean and what bearing did that have on his accomplishments with the gallery during his nine years in New York? It was said with both tristesse and finality. Chapter closed and yet, after my mother’s death, I find myself wanting to know more.

[8]

[8]Gerhardt Eisler, the older brother of the composer Hanns Eisler, was a well-known communist, having been a member of the party in Weimar, Germany. Accused of having lied on his immigration application to the U.S., he was under indictment, out on bail after two trials. He was suspected of being a spy and was cited in Time magazine in 1948 as America’s number one spy. Sought by the FBI, with the HUAC trials underway, he stowed away on the M.S. Batary in May of 1949, using a false name. The crew discovered him and turned him over to the British upon arrival at Southampton. But the British did not return him to New York, instead let him travel onto the newly forming German Democratic Republic, the DDR or, East Germany, where he would soon become a prominent leader. Alexan and his family also traveled to the DDR on the same board, which is also confirmed by Alexan’s daughter’s accounting. Alexan went on to become both a literary translator and the editor of the USA in Wort und Bild.

According to his daughter, Alexan paid for and arranged for Eisler’s passage. Just how well did Alexan know Eisler?Were they friends or did they work together? These are unanswered questions. Yet having to “flee” and arrange the abrupt transfer of the gallery’s title and holdings to my mother, age twenty-five, would suggest that he was in fear for his life, and that he knew where he was going when he left. Not to England but to the DDR. It is not surprising that his essay on Käthe Kollwitz was titled: “Art and Propaganda.” The question remains, what did my mother know? Bernice never spoke about him other than to express admiration for this mysterious man, known as Alexan.

My mother continued the gallery for several more years. Her commitment was to social realism, and to Neo-romanticism, as Devree had commented on in the Times years before. In the end, she sold the remaining contents of the gallery to a dealer who would quickly move away from the founding principles and leave the subway arcade. My mother would champion the art to me for the rest of her life while refraining, almost entirely, from talking about these years. She never told me during her lifetime, and she told me a lot, that my father, a lawyer, defended Irma Jurist, a composer, before HUAC. In later years, at one of the legendary Brown salons, as I sat in a room with Alger Hiss, Raphael Soyer, and Jack Levine, I heard Mainey emphatically state: “We were wrong. Wrong about Stalin.” My mother could never say those words. The door had shut. She had lost her husband, had two young children, and the dreams of her youth were gone. She found herself in a new world by the mid-sixties and rather than look back, she looked forward. She jumped in with the same bravery that her youthful idealism displayed and turned first to dance and then to music for self-expression, always repeating the cri de Coeur: the rights of man, freedom. But her enigmatic portrait remained in the dining room for fifty- seven years and on the back of the frame the sticker: The Tribune Subway Gallery.

- [Image]: https://asllinea.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/5.-Bernice-Sacks-studio-portrait-February-1947-scaled.jpg

- Ichiro Fukuzawa: https://artscape.jp/artscape/eng/ht/1905.html

- [Image]: https://asllinea.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/4.-Tribune-Subway-Gallery-brochure-The-Unknown-Van-Gogh-essay-by-B.-Z.-Sachs-September-October-1947-e1633987016573.jpg

- American Painting from the Armory Show to the Depression: https://www.amazon.com/American-Painting-Armory-Show-Depression/dp/0691003017

- [Image]: https://asllinea.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/8.-Bernice-and-Raymond-Sacks-September-1945.-Last-day-in-the-US-before-Ray-leaves-for-Japan.-scaled-e1633985569625.jpg

- [Image]: https://asllinea.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/2.-Tribune-Subway-Gallery-brochure-Nineteen-Unknown-Soldier-Artists-in-Postwar-America-essay-by-Leonard-Baskin-May-June-1948-scaled.jpg

- [Image]: https://asllinea.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/6.-Bernice-Sacks-self-portrait-late-40s-scaled.jpg

- [Image]: https://asllinea.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/7.-Bernice-Sacks-sketch-of-Georg-Friedrich-Alexan-1947-scaled.jpg