Alfredo Ramos Martínez’s Calla Lily Vendor from 1929 is a beautiful painting. Entering the Whitney galleries, I thought I was walking up to one of Diego Rivera’s Flower Vendor series. It wasn’t what I thought it was at all. This was not a painter I was familiar with, and it made me wonder, Was he a follower of Rivera’s?” It was easy to find a Rivera nearby to compare birthdates. Martinez was some fifteen years older than Rivera, and this painting predated Rivera’s Flower Vendor by several years. “Who influenced whom?” I thought. As it turns out, this could be the theme of the exhibit of Mexican and American art at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Vida Americana: Mexican Muralist Remake American Art, 1925–1945 is an exhibit about artistic cross-fertilization. Whereas American art in the first half of the twentieth century is generally considered to be influenced by and reacting to trends coming out Europe, this exhibit demonstrates that a significant influence on American artists came north from Mexico. The influence of the big three Mexican artists, Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros form the core of the show. Their socially-conscious and very political art found fertile ground in America during the years of the Great Depression. Young American artists were drawn to their powerful art that had a clear political agenda: art designed to make a difference. Compared to the early waves of puzzling European modernism sweeping American shores, increasingly abstract and appealing to cultured elite, Mexican art must have seemed refreshingly accessible and relevant. A generation of artists who wanted to make a difference in the world found artists whose huge frescos were often political manifestos. The art of the 1930s needed its own schema to reflect the great national suffering. They found it in the passionate and fierce subjects of the “big three” painted with a bold expressiveness that stayed safely within the borders of representational art. They painted the working people, scenes of injustice and cruelty from the Mexican revolution, art that was a critique of society, and a call to action. Their art was meant to have a vital function in society, not a decorative one. The appeal of art that makes a difference is obvious to a generation coming to maturity in the economic and social collapse of the 1930s.

The impact of the 1913 Armory Show that introduced European modernism to America set off a new mania for the “new,” eschewing the traditions of a culture that would soon be subsumed in the throes of WWI. The news of fresh voices out of Mexico, foreign enough to be exotic but close enough to be accessible, must have been intriguing. Rejecting European influences in favor of their own vernacular, focusing on the experiences of the ordinary people, their art was born out of political turmoil that had resonance amidst the upheavals of the Great Depression.

Of course, the United States already had a rich tradition painting the ordinary people. George Caleb Bingham, Thomas Eakins, Winslow Homer, and active in the early twentieth century: George Bellows, John Sloan, the Art Students League-based Ashcan School, and Thomas Hart Benton. However, the work from down south was political in a very direct way. The overt politics of the Mexicans was pro-working class and also Communist. This is where the Mexicans clashed with the Americans, most famously in Rivera’s Rockefeller Center mural that was destroyed because he wouldn’t remove Vladmir Lenin’s face. Rivera recreated this fresco in Mexico as Man, Controller of the Universe, in 1934. (It is reproduced at scale in the exhibit.) American artists were all for the poor and working class, but drew the line at promoting Communism. Images of working people, oppression, war, and labor strikes abound in the Americans’ work, and though their politics may be left, overt references to Communism are absent. The American art seems to me to be dark genre images of America at that point in time, visual exposé, while the Mexicans were revolutionaries.

The exhibit at the Whitney provides a huge sampling of art by both Americans from the period and many Mexican artists less known than the big three. The scale printed reproductions of the frescoes, like the panoramic of Rivera’s Detroit Industry, is a total treat. Short of a pilgrimage to the actual locations of the frescoes, this is as good as it gets. The experience of scale does matter even if other qualities of the viewing experience are lost viewing a print instead of a genuine fresco.

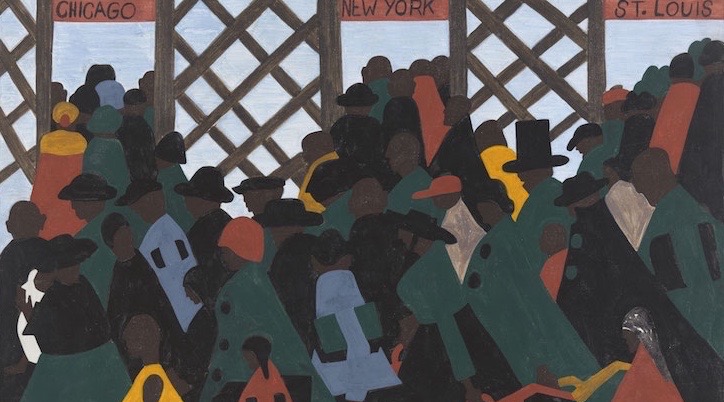

Frida Kahlo is well represented, but to me she never fits in with any group. She is her own movement. Thomas Hart Benton is well represented and many of his students are also there. Benton, who taught at the Art Students League in the early thirties, attracted the same type of young artist who were also attracted to the Mexican artists. There are no fewer than twenty Art Students League artists in the exhibit. The extent of the lists of League artists is startling: Will Barnet, Charles Alston, Harry Sternberg, Ben Shahn, Jackson Pollock, Xavier Gonzalez, Charles White, Jacob Lawrence, Eitaro Ishigaki, Philip Guston, Reuben Kadish, Fletcher Martin, Edward Millman, Seymour Fogel, Emil Bisttram, Philip Evergood, Marion Greenwood, Elizabeth Catlett, and Jacob Burck. This is just a list of American artists in the exhibit; an inclusive list of Americans impacted by Rivera, Siqueiros, and Orozco would be long indeed.

Americans like Jackson Pollock were probably more taken by the expressive power of Orozco’s style than his politics. Siqueiros’s Experimental Workshops, held near Union Square, are well known to have had a profound impact on Pollock. Siqueiros felt that artists could not make revolutionary art using the traditional techniques. They studied controlled accidents in paint. Thirty years ago I had the pleasure of knowing Axel Horn who participated in those workshops in his youth alongside Pollock. Axel is quoted in the Whitney catalogue. I remember Axel describing to me how they put pots of paint on a lazy Susan and spun it. Paint spattered and splashed, and they all held their chins and said “Hmm.” It seems only Pollock absorbed the potential of what they were dabbling with, the very beginnings of Abstract Expressionism. This is a vital point in the exhibit. Abstract Expressionism has acknowledged roots in European art and the influence of George Grosz, but the Mexicans haven’t been given their fair share of the credit.

But did Mexican artists remake American art? They were definitely part of the cross-fertilization that was a vital part of the American art scene. I think the inclusion of Benton in the show demonstrates his kindred spirit, but I don’t think his art is a result of the influence of Rivera, who he knew in Paris when they were both students. It was the era of social realism in the Americas, not to be confused with the socialist realism in parts of Europe and the Soviet Union. This was not government driven propaganda, but the art of “the people.” The political art of the Mexicans had a tremendous stylistic influence on young American artists who would go on to create many WPA murals. But it was different, infused with the Regionalism promoted by Benton and the American realists. In an exhibit about influences, the elephant in the exhibit is still France. Of the big three, Rivera and Siqueiros studied in Paris and absorbed European influences. The Americans had been absorbing European influence from the beginning. Mexico has had European-style painters since the Baroque. As much as they all tried to shun centuries of European tradition, it was too deeply embedded to allow for something purely new. For that they should have looked more to indigenous art. Instead, the work we see in the exhibit reflects a cross-fertilization of Mexican, American, and yes, largely European influences. The style of Max Beckman, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, and Franz Marc don’t look all that different if you can image them painted as frescoes. Piero della Francesca comes to mind as well. The European styles brought back to Mexico were fused with Mexican subject matter and revolutionary zeal, traveled north where the enthusiasm for art that makes a difference was grafted onto the new offshoots of American realism. Eventually the search for a new revolutionary language, encouraged by Siqueiros, fosters the New York school which in turn will re-cross the Atlantic. Furthermore, where, in all of this, do you place the influence of Picasso? And would the art that made its way to North America appear that way it did without the influence of African art? Art is the eternal conversation between cultures across time. Maybe it is not so important who gets credit for what, but rather whether the results were any good. Who cares where it came from if it’s bad. Is the work of this art historical period great? Well, I would say that there is a lot to criticize and a lot to celebrate. I find the work extremely engaging on several levels, but in terms of the aesthetic appreciation of great painting? Well, it falls a bit short for me. I find the subject matter more engaging than the visual language used to convey it.

Vida Americana is a must-see exhibit, thought-provoking and rich. Many Art Students League artists are seeing the light of day who have been moldering in the margins, and the zeitgeist of the American art scene between the wars gets some well-deserved consideration. It is also worth a collective reminder that North America doesn’t start at our southern border.