Walter Sickert rates high on my list of favorite early twentieth-century artists. He has become my go-to example when I’m struggling with a figure painting and decide to dispense with propriety, loosen up and get a bit dark. Sickert was very good at getting dark. He dug into the lower crust of London, its grubby boudoirs and domestic boredom, with an almost Dickensian appetite. A few generations of British painters, including Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon, Frank Auerbach, Ruskin Spear, William Coldstream, Euan Uglow, and Bernard Dunston, are nigh unimaginable without Sickert as a precursor. He is, at the very least, England’s bridge from the European masters of the late nineteenth-century to those of the late twentieth. His historical place secure, I’m not sure I accept the attempts to cast Sickert as a modernist. During his life, modernism moved increasingly away from figuration and narrative painting, two elements of the utmost importance to Sickert.

Every few years Sickert is the subject of a major exhibition in England, often focusing on one facet of his career, and I have the catalogues to prove it: the Venetian works, the Camden Town series, and a show in which he shared billing with Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec, an exhibition I lucked into at Tate Britain during a visit to London in 2005. He’s at the Tate again this summer, this time the subject of a comprehensive retrospective, nearly thirty years after the last one at the Royal Academy. One wonders whether most museum goers will leave with a more nuanced understanding than the headline of a Guardian review, which called the artist “a master of menace.” Sickert’s public notoriety, such as it is, owes to the debunked claim that he was a serial killer. It’s a public relations department’s dream: the Tate website features the boldface declaration that Sickert was not Jack the Ripper.

The show is divided into eight sections, with several sub-sections, covering Sickert’s biography and various genres. It begins with self-portraits. In the wake of crime novelist Patricia Cornwell’s psychological speculations, too much has been made of a sinister persona as registered in the self-portraits; she asserted his was the face of a murderer. Perhaps the finest of the self-representations is The Studio: The Painting of a Nude, which shows only his arm, mixing paint on the palette, a foil to the backlit model standing before him. It is, to my eye, a perfect painting, one of the best takes on the artist/model theme ever painted.

Sickert was born in Munich in 1860, and moved to England when he was eight. After working professionally as an actor—an experience that sharpened his eye for composition, lighting, role playing, and narrative content—he enrolled at the Slade School of Fine Art in London. He left after a few months for more rarified environs. By 1882, Sickert was the studio assistant to James Whistler, from whom he learned to paint directly from life. He befriended Degas in 1885, and would later refer to the Parisian artist’s studio as “the lighthouse of my existence.” At Degas’s advice, Sickert started using drawings as reference for studio-produced paintings. These were arguably the two most trenchant masters of the era; it is irresistible to assume that their mentorships bolstered the younger man’s inherent misanthropy. What is certain is that they confirmed his direction as an artist and influenced his choices of subject matter.

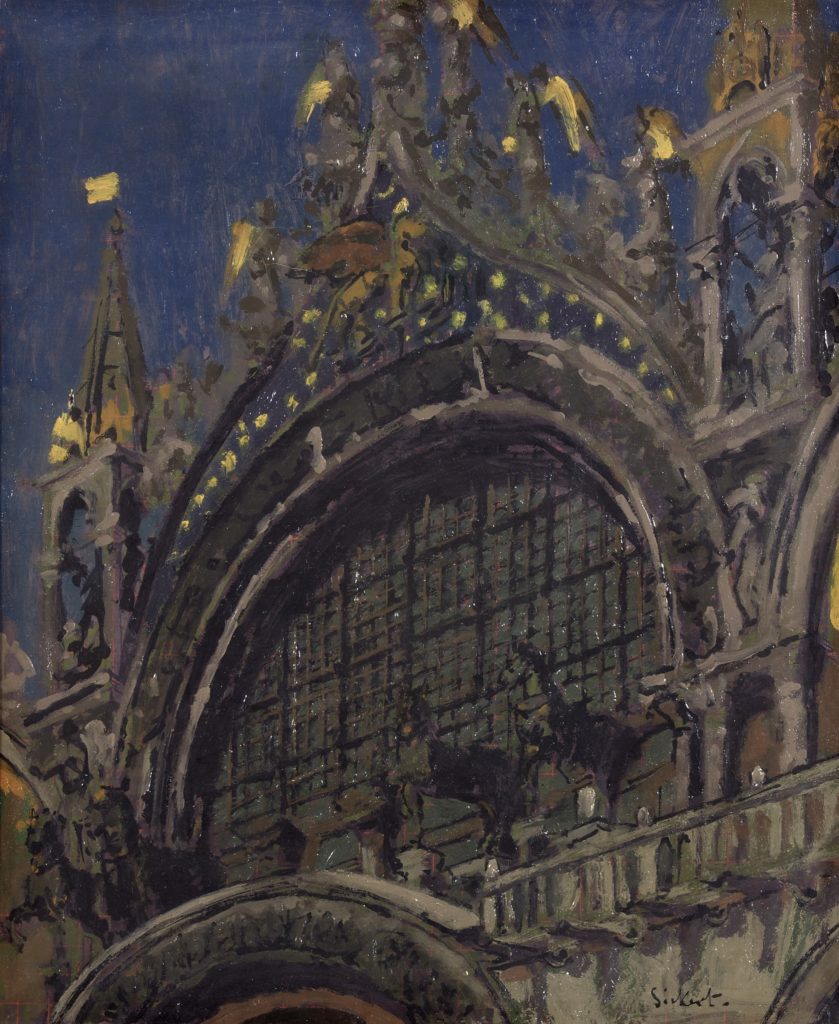

Even when these influences are most pronounced, as in the paintings of music halls and voyeuristic nudes that announce a debt to Degas, the resonance of Sickert’s voice is clear. The music hall scenes that occupied him for a decade beginning in the mid-1880s are more boisterous and freer in handling than Degas’s concert pictures. Works like Gallery of the Old Bedford, suggestive of the odd perspectives Degas favored, go further in capturing the noise of working class leisure. His most famous painting, Ennui, is the direct descendant of Degas’s Sulking, and as late as 1920, Sickert was still paying homage, as in The Trapeze, an echo of Miss La La at the Cirque Fernando. Similarly, Sickert’s early landscapes of Dieppe shopfronts are derivations of Whistler’s paintings of the same subject. Soon enough he showed a preference for bolder value and color contrasts, with diagonal streets bringing the eye through dramatic light and shadow patterns. In Dieppe, the culminating point was sometimes the facade of the church of St Jacques. For La Rue Pecquet from 1900, the artist snuck up on St Jacques from a back street. Sunlight rakes across the dark stone architecture, carving out blackened hollows in doorways and windows. When Sickert went to Venice—a site Whistler had once staked as his own—he painted large canvases of San Marco with jewel-like colors; it is curious that this iconoclast found pictorial refuge in the grandiloquent facades of ancient churches. He reveled in the scenery during multiple visits to Venice. When the weather there turned inhospitable during his visit in 1903, Sickert stayed in his room and painted prostitutes, sometimes seated in pairs, sometimes as single portraits.

The rain-induced Venetian interiors set in motion the nudes that Sickert painted after he returned to London, though it would be five years before he started the most controversial works. They strike a different and far more disquieting cord than those of his predecessors. Whistler’s watercolors and gossamer pastels hint at seduction. Degas essays the nude coolly, furtively—his boldest narrative foray was an early painting of ambiguous meaning, Interior, sometimes called The Rape. It foretells the Camden Town series, but whereas the older artist may have used a literary passage by Zola as inspiration, Sickert turned to current events. The specific event he chose was the lurid murder of a prostitute in the Camden Town section of London in 1907. Thence was spun a profusion of drawings and paintings of nudes in rooming houses, sometimes accompanied by clothed male figures. The subject afforded Sickert a platform to challenge what he considered the insipid idealizations of academic figure painting, and to replace them with a modern realism (Interestingly, scholar Lisa Tickner writes that “simultaneously Sickert was fighting a rearguard action against the rejection of narrative in modern painting.”) The murder was never shown in Sickert’s iterations of the theme; moreover, titles were interchangeable. One painting and its related drawings have been known as both The Camden Town Murder and What shall we do about the Rent? It is entirely plausible that Sickert manipulated his audience by placing provocative titles on cryptic scenes. Art historian Quentin Bell believed that the titles were “added haphazard for the sake of a private joke or the better bamboozlement of later historians.”

Often singled out as the most disturbing painting in the series is L’Affaire de Camden Town, wherein an exposed and dramatically foreshortened woman appears to cower in bed, beneath the presence of a fully dressed man who looms above her with arms crossed. Yet, like other paintings in the series, its meaning is ultimately unknown. As art historian Barnaby Wright has noted, “The male figure’s folded arms may also be read as benign rather than aggressive.” In a related drawing, the standing man was substituted by a clothed woman, engaged in conversation with the reclining figure. Very different narratives could be created from the same compositional source.

Sickert’s obsession with the macabre went beyond Camden Town. When his landlady claimed to know where Jack the Ripper had lived, Sickert rented the room. This and other circumstantial evidence were the basis for Cornwell’s conclusion that Sickert was himself the infamous murderer of Whitechapel. Dedicated Ripperologists don’t take the finding seriously, in part because Sickert was in France when some of the crimes occurred. There is a case to be made that the Camden Town paintings objectify and dehumanize women. As far as this goes, the misogyny of critics is more telling than the paintings themselves: when Dawn, Camden Town (then titled Summer in Naples, further evidence of Sickert’s “haphazard” use of titles) was exhibited in 1912, reviewers were appalled by the female model, calling her a “hideous, middle-aged woman,” “dirty complexioned” and representative of “musty, flabby realities.” The appearance of a woman who wasn’t sufficiently attractive seemed to be reason enough to take offense. Sickert was correct to denounce the idealized female nude as “an intellectual bankruptcy that cannot but be considered degrading,” yet the Camden Town pictures presented another degrading identity, that of victim, rendered doubly vulnerable in her nudity. The realism of Sickert’s vision shared something integral with the ideal against which he rebelled: the dominance of what is now called the male gaze.

The abiding tone of the scholarship is to describe these works in bleak terms, but they are invigorating in color and handling. Nudes that are peripheral to the series proper—The Iron Bedstead, Nuit d’Été, Mornington Crescent Nude, and La Hollandaise—are erotically charged tableaux and scintillating color studies. Sickert chose subjects that were distasteful to most viewers, and conveyed them with a physicality that fits the mood, pigment excitedly dragged, splotched and dotted upon the canvas. As examinations of natural light, these are the best paintings he produced. Marjorie Lilly, an artist who met Sickert in 1917, accompanied him “climbing rickety stairs” in London walk-ups while he searched for the right studio: “All I saw was a forlorn hole, cold, cheerless … All he saw was the contre-jour lighting that he loved, stealing in through a small single window, clothing the poor place with light and shadow, losing and finding itself again on the crazy bed and floor. Dirt and gloom did not exist for him; these four walls spoke only of the silent shades of the past, watching us in the quiet dusk.” This anecdote underscores the significance of light and mood in Sickert’s paintings. We follow the light as it passes through cheap blinds, washes across rented rooms and illuminates the bedsheets and indolent bodies of his subjects. Robert Upstone, a former curator at Tate Britain, noted a “close correlation” to the interiors of Vermeer and Dutch painting, which is less far-fetched than it sounds. Perhaps these were the “silent shades of the past” that Lilly invoked. Another similarity comes to mind, especially since I’ve returned to teaching at the League this week. The rich, dark tones of Sickert’s interiors remind me of the light and shadow effects in New York City studios. Artists recognize the solemnity of natural light as key to a shared language.

The Camden Town paintings do tend to take the oxygen out of the room. They are the works that London reviewers fastened onto this summer (“serial killer, fantasist or self-hater?” asked Jonathan Jones), but they were mostly painted in 1908, and represent a fraction of Sickert’s creative output. There are many other paintings here worthy of mention, among them the early music hall scenes like The P.S. Wings in the O.P. Mirror; a breathtaking interior with a shimmering still life (The Mantelpiece); urban views like Maple Street, London and Le Grand Duquesne, Dieppe; The Horses of St Mark’s, Venice; domestic corrosion (Ennui and Off to the Pub) and idiosyncratic portraits (Aubrey Beardsley and Mrs Swinton).

Sickert’s prime lasted a few decades, long enough to establish him as the greatest English artist of his era. By the time he matured as an artist, he had emphatically distanced himself from at least one of his mentors, rejecting Whistler’s aesthetic credo of art for art’s sake. For Sickert, “painting is a rough-tongued, hard-faced mistress, and her severe rule will brook no dallying of that sort.” Tough talk. One can take this statement, like his narrative work, at face value. Or it may be understood as part of a complex balancing act between a deeply held conviction of what constitutes realism, love of the act of painting, and a lifelong talent for playing the role of provocateur.

Walter Sickert is on view at Tate Britain through September 18, 2022.

JERRY WEISS (@jerrynweiss) teaches Drawing from Life and Painting and Drawing from Life at the Art Students League of New York.