[1]

[1]In 2005, while installing a show of my sculpture at the University of Maine at Machias, I encountered an intriguing object. Flanking the entry to Powers Hall, home of the art department and gallery, was a bronze statue of heroic-scale: a masterful female figure, nude from the hips up, posed on one knee. While it was worthy of interest for its own sake, what caught my eye was the signature at the base: Zorach. The name meant more to me than to a casual observer. I had studied at the Art Students League of New York in the 1990s and served as a monitor for Sidney Simon, who introduced me to the work of William Zorach. Simon spoke of Zorach as his distinguished predecessor, though there were thirteen years between Zorach’s retirement, in 1960, and Simon’s hiring, in 1973. While a student, I had restored the surface and renewed the patina of Zorach’s plaster of Ben Franklin, which stood in the vestibule of the first floor studios. Moreover, I suspected I had heard echoes of Zorach’s art teaching even though he had left over thirty years before I arrived. Instruction at the League was like the clay one took from the bins. While fresh was continually added, some of what one found there remained from decades past.I felt a personal connection with that bronze in Machias by virtue of my New York experience, and wondered how it had come to be there. Sidney Simon, a founder of the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, had said Zorach taught a few summers at that institution, so I knew he had ties to Maine. I also knew Zorach had maintained a studio in Brooklyn, where another of Sidney’s students, Gary Sussman, had reassembled the pieces of Zorach’s Ben Franklin statue. It is a long way from Machias, a small coastal city twenty miles from the Canadian border. Here was a mystery.

[2]

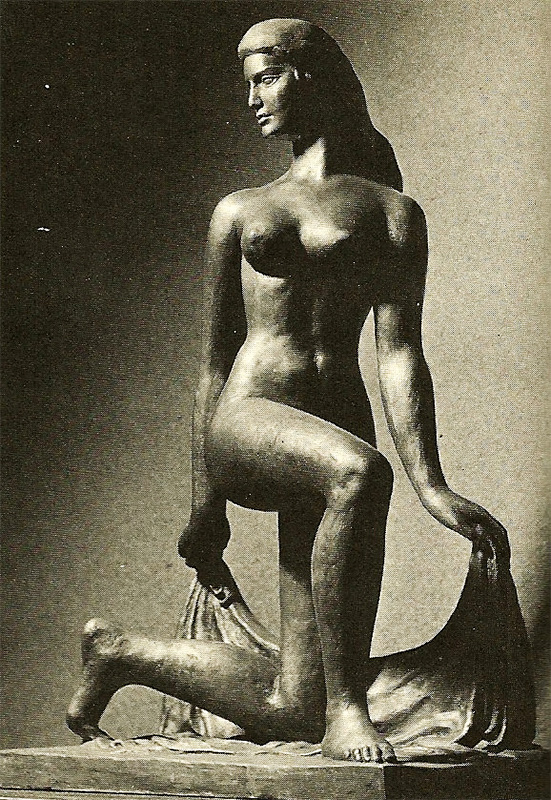

[2]Five years later, in April 2010, I visited the library at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, where a pair of Zorach’s bronze pumas flank a passage in the West Building. I discovered from a catalogue there that Zorach maintained a residence and studio in Georgetown, Maine. He had also received an honorary degree from Bowdoin College in Brunswick, where my parents had recently moved. With heightened purpose, I visited Bowdoin College’s fabulous Walker Museum of Art. This time, I paused an extra minute before Zorach’s granite head of his wife, Marguerite. On the way out I mentioned my interest to the receptionist, who told me the sculptor’s daughter lived in the area and that I should contact her by phone. That evening I spoke to Dahlov Ipcar, who, I was to learn, is a leading Maine artist, and a story in herself. She knew the Machias piece and its name, The Spirit of the Sea. She also suggested I find and read her father’s autobiography, Art is My Life (1967).This book answered many questions. Zorach’s family fled anti-Semitism in Lithuania when William was six and settled in the slums of Cleveland, Ohio. He could draw well and trained in a lithographic shop, but broke away at eighteen to study at the National Academy of Design in New York. At twenty-two, he went to Paris where he met his future wife, Marguerite. He made his first sculpture in 1921 at the age of thirty-four. The following year he bought a house and land at Robinhood Cove in Georgetown, Maine and maintained his legal residence there, though he also kept a house and studio in Brooklyn. To supplement his income from sculpture he took a post at the Art Students League in 1929, which he held until 1960. The book told much but not the whole story of the statue in Machias. Spirit of the Sea was apparently a duplicate of a work Zorach made in 1961 for the City of Bath, Maine. This, the first cast, stands newly restored in a park opposite the Patten Free Library about eight miles from my parent’s place in Brunswick. The piece is analogous to a work the sculptor had made three decades earlier for Radio City Music Hall in Manhattan, Spirit of the Dance, and not in name only. Both are female figures of a similar scale who rest on one knee. If standing they would be nine feet tall. As their names and ideal features suggest, they come from the realm of icon and archetype. They are larger than life, and their histories are similar. In 1930 Zorach was asked to submit drawings for a work to grace the lobby of what was to be Radio City Music Hall in Rockefeller Center. It was during the Depression, so only $850 was available, enough for a thirty-six-inch figure. Zorach made a model, but soon realized it was far too small for the intended space. He scaled it up to over six feet for free just to give the project a fitting piece. Cast in aluminum to save money, it stands to this day. Thirty years later the Bath Garden Club approached the sculptor for advice on creating a fountain to enhance a small pond in the city park. On reflection, Zorach offered to design and make a figurative fountain, the centerpiece of which was to be Spirit of the Sea. He would donate his time and talent if funds for casting and other costs could be raised. Between his sculpting and a good many bake sales and raffles, the project came to fruition and stands, recently refurbished, in Library Square Park today.

[3]

[3]While the Spirit of the Dance (1932) and the Spirit of the Sea (1962) are akin in many ways, their differences are telling. The earlier figure strikes a complex and elegant pose. Spiraling subtly to the left, the classically proportioned dancer takes a knee as if curtsying at the conclusion of her act. Behind her, she hangs a drapery from either arm, which suggests a stage curtain. Her refinement suits the intended setting, a showcase for performing arts regularly inundated with sophisticated metropolitans. Zorach gambled on their tolerance in making her wholly nude, a bet he nearly lost when the piece was refused and removed for a time on that score. In contrast, Spirit of the Sea strikes a simpler pose, wholly frontal but for the right-turned head. It is simpler, but more dynamic: a feeling of action derives from the strong left oblique of its basic shape, which from the main view is not a static isosceles, but an irregular triangle. The right profile undulates, wavelike, from lowered knee to upraised hand; the left bends angularly like a jagged coast. Where they meet, at the apex, the cupped hands suggest waves breaking on a shore. The bold figure befits a work intended to face the elements of coastal Maine. Here, Zorach took no chances with the townspeople of Bath, draping his figure from the hips in a rather aqueous skirt. Iconography and audience account for some of the differences between the two works. Others reflect changes in the artist and his outlook. Zorach was forty-three and at the height of his energy when he made the Rockefeller Center piece. His drive must have been extraordinary as he made the mold and cast the plaster himself. The complex design necessitated casting in several pieces and re-assemblage: a colossal undertaking. Thirty years later, at seventy-three, he might have considered casting as he designed Spirit of the Sea. Here, the drapery, which would have been cast separately for the earlier work, simplifies the job: a three-piece mold could well have sufficed to cast this piece.

“To me, direct sculpture is greater than modeled sculpture,” Zorach wrote. “Its problems are greater and its possibilities of creative expression are deeper: more goes into it, not just in time and work, but in creative thought and feeling.”

The shift from the open format of the Spirit of the Dance may also reflect the sculptor’s predilection for stone carving. When he made the earlier piece, Zorach had only been sculpting for nine years and was still exploring the art’s many branches. In any case, consideration of carving must have been far from his mind. The open pose, with the enormous projection of the raised thigh, and the extension of lowered leg and foot far beyond the torso mass, make a design that would have been most uneconomical to carve. Later in his career, Zorach’s preference for direct carving came increasingly to the fore. Gary Sussman [4] said that Zorach, if he had had the choice, would have carved stone exclusively. And Zorach himself wrote in his autobiography, “In the last years I’ve gotten so involved in stone and get so much pleasure out of it that I think in stone.”

[5]

[5]Spirit of the Sea recalls a carving from the late 1940s, the Bestowal, or Kneeling Girl, which I know from a bronze cast in the collection of the artist’s daughter. Both are female figures on one knee. Zorach favored carving figures on one knee—another example is his granite Football Player (1931) at Bowdoin College—and with good reason. Many well-proportioned blocks are too squat to accommodate a standing figure, yet too tall for a seated figure; for such, a kneeling figure is a good bet. A pose on one knee offers more variety than one on two. For such a figure the raised lower limb presents a design challenge as its projection invariably pushes the boundary of the block. It certainly was a major element in Spirit of the Dance. In the Bestowal, Zorach kept the wayward knee within bounds by the simple expedient of making the thigh shorter than in nature. The device apparently so pleased him that he had an edition of six casts made from the stone, and later used it in his design for Spirit of the Sea, in which the raised upper thigh is likewise disproportionately short. “To me, direct sculpture is greater than modeled sculpture,” Zorach wrote. “Its problems are greater and its possibilities of creative expression are deeper: more goes into it, not just in time and work, but in creative thought and feeling.” While he clearly favored the direct approach, throughout his career he undertook commissions that required committee approval. In these instances, he made a scale model, and then, upon approval, a full-scale enlargement. This was his expedient for both Spirit of the Dance and Spirit of the Sea. The latter is a straightforward enlargement of the twenty-eight-inch maquette he presented to the Bath Committee. Scaling it up was a big job, but mechanical rather than creative. The result, in his mind, almost necessarily lacked the charm of his direct work. Having enlarged the Rockefeller Center piece in clay, and cast it in plaster for free, Zorach ordered a second cast in bronze in hopes of a sale. He also had his thirty-six inch model cast in an edition of eight. The second full-scale cast toured art museums in the U.S. as far as the West Coast, garnering plaudits but no offers to buy. Zorach finally shipped the piece to his own property in Maine and set it up, where it overlooks Robinhood Cove today. I guessed that William Zorach, having also taken no money for making the Bath piece, likewise ordered a second bronze in hopes of eventual sale. I know that he ordered an edition of six maquettes. He made no mention of such a cast in his book, however. The good ladies of the Bath Garden Club were unaware of a duplicate, and, as one appeared in Machias, there was a local uproar. They evidently thought that, having worked so hard to raise casting funds, the piece was to be theirs and theirs only. The University of Maine at Machias was able to tell me that they received Spirit of the Sea in 1988. Could it have been made as late as that date, twenty-two years after the sculptor’s death? The Zorach family records had no answer as they typically do not include dates of duplicates. Andreas Van Heune, a sculptor from Bath associated with a recent restoration of Spirit of the Sea, gave me the name of the foundry: Bedi-Rassi, now Bedi-Makky [6] in Brooklyn. I called there and spoke with Istvan Makki, the owner. He remembered Spirit of the Sea very well as he had done both castings himself by the French sand-cast method, his specialty. Offhand, he thought years had separated the first and second casts, but could not say how many. He told me how, in his last years, Zorach brought his son, Tessim, to meet Makki at the foundry, so that the two might know each other well. He said Zorach left the editions of many pieces unfilled at his death and that it was his intent Tessim and Makki complete them, market permitting, for the benefit of the grandchildren. Could Tessim have ordered the casting of the Machias piece? Mr. Makki could not remember. He said he would tell me only what he knew for sure, and kindly went through his records. While fairly complete records went back only to 1970, when he had assumed ownership, he said he had found evidence that the sixth and final cast of the maquette had been in June, 1966, closing the books on Spirit of the Sea within the sculptor’s lifetime. So Zorach himself had ordered a second copy of Spirit of the Sea, as he had thirty years earlier in the case of Spirit of the Dance, in hopes of getting some return for his labor on them. While Spirit of the Dance toured the nation in the 1930s, Spirit of the Sea went straight into storage at the Hahn Fireproof Warehouse of Jersey City, where it remained for over two decades. The piece, like the Spirit of the Dance duplicate, might still be the property of the Zorachs had it not been for the generosity of an old family friend, Norma Marin, the widow of John Marin, Jr., and the daughter-in-law of the painter John Marin, who, incidentally, also taught at the Art Students League. The University of Maine, which furnished me her name, offered no clue as to her motive. The Marins figure prominently in William Zorach’s autobiography. “One does not seem to make close friendships with people later in life,” Zorach wrote. “It is only in youth that one makes close friends.” Zorach met Marin early, on his first trip to Maine, in Stonington during May 1919. Marin, seventeen years Zorach’s senior, served as an early mentor. We know that Zorach consulted Marin when contemplating a trip to California and Yosemite and that the latter encouraged him to go. When the families first met, John Marin, Jr. was a little boy running wild in a Maine coast fishing town. Later, it is clear the Zorachs and the younger Marins, John, Jr. and his wife Norma, became good friends. They visited back and forth. The Marins lived in Manhattan, but spent summers in Maine, John Marin, Sr. having bought property on Cape Split in Addison in 1934. The Marins would stop overnight with the Zorachs in Georgetown, both driving up the coast and on the return to New York. For their part, each August the Zorachs drove up to Cape Split. The couples went sailing on Pleasant Bay and went ashore on Flint Island. Its beach stones so impressed the sculptor that he loaded the boat with as many as it could hold. He took such findings to his studio, carved them, crated them, and sent them on to his gallery with the Marins when they stopped on their return trip. He did a portrait of little Lisa Marin. This is a story of more than passing friendship: a rare thing in life. When her husband died in 1988, to honor his memory, Mrs. Marin evidently remembered the good times she and her husband had shared with the Zorachs. Accordingly, she arranged with Tessim to rescue Spirit of the Sea from its storage-warehouse oblivion and give it a home in fresh air. Spirit of the Sea is best seen in Bath, where it surmounts a fountain ensemble. There it rests in a seven-foot granite basin atop a four-foot diameter granite drum. These, firmly rooted on concrete pilings, rise in the middle of a pond. Water travels up piping concealed in the drum, swirls into the basin and overflows in sheets into the pond below. It is the focal point of the principal city park, a spacious, well-landscaped square fronting the city library. As the overall height of the ensemble is fourteen and a half feet, the viewer positioned at the water’s edge sees the statue from below. Quite possibly Zorach, who engineered the whole, took this into account when designing his piece, which to me looks more dynamic when seen from below than it does head on, as one sees it in Machias. Also, while it is out in the open in Bath, it is in a confined space in Machias, where luxuriant shrubbery threatens in the growing season. For all that, it is better to see it as it is in Machias than not to see it at all. There it is prominent from U.S. Route 1, the coastal artery. And, as it flanks the entry of the university’s art department, one likes to think it affords some students with a vision of what is possible in sculpture. For further reading— Malvina Hoffman, Heads and Tales (1936) _____. Sculpture Inside and Out (1939) William Zorach, Zorach Explains Sculpture (1947) _____, Art Is My Life (1967) Among the many who contributed to this article, a few who went out of their way to help me deserve mention: Dahlov Ipcar and her son Bob; Dr. Peter Zorach; Norma Marin; Andreas Van Heune, sculptor, of Bath, Maine; Istvan Makki, foundryman, of Brooklyn, New York, and especially Bernie Vinzani, Chairman of the Art Department, University of Maine, Machias. My neighbor Peter Knuppel cheerfully furnished use of his computer on several occasions. Lastly, to my collaborator Eric S. Beckjord, who prepared the manuscript and other materials for electronic submission, I say, Thanks, Dad.