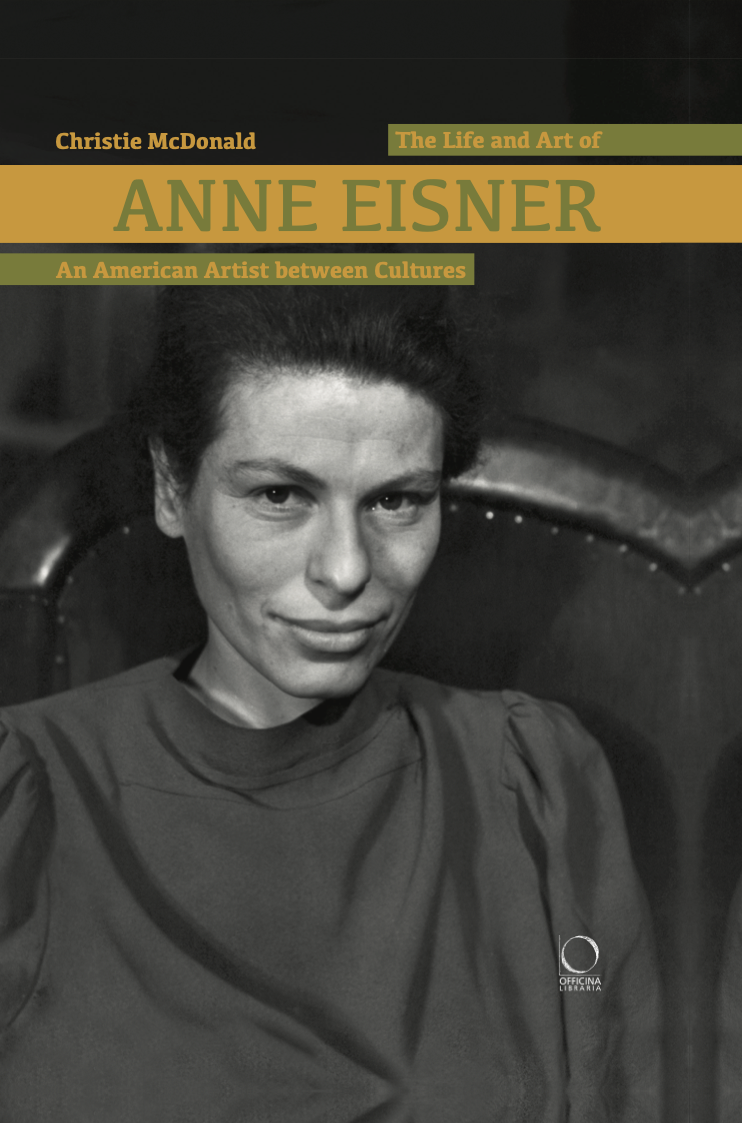

The Life and Art of Anne Eisner (1911–1967): An American Artist between Cultures traces Anne Eisner’s life from her early life and artistic career in New York, through living at the edge of the Ituri Forest in the former Belgian Congo, now the Democratic Republic of Congo, to her return to New York. Anne Eisner came of age in the 1930s and 1940s, during the struggle among artists and intellectuals to combat fascism and create a better world. Having studied at the Art Students League and leaving behind a successful career as a painter, Anne followed Patrick Putnam, with whom she had fallen passionately in love, to Epulu, a multicultural community he had founded in the 1920s. As an American woman and painter, Anne’s focus on cultural and aesthetic values and her belief in freedom and equality brought an eccentric perspective to the colonial context. Unanticipated challenges forced her to think about who she was, as she agreed to marry under unfamiliar conditions, became “one of the mothers” in the community, hosted researchers and tourists, and attempted to care for Putnam in his tragic decline.

The Life and Art of Anne Eisner (1911–1967): An American Artist between Cultures traces Anne Eisner’s life from her early life and artistic career in New York, through living at the edge of the Ituri Forest in the former Belgian Congo, now the Democratic Republic of Congo, to her return to New York. Anne Eisner came of age in the 1930s and 1940s, during the struggle among artists and intellectuals to combat fascism and create a better world. Having studied at the Art Students League and leaving behind a successful career as a painter, Anne followed Patrick Putnam, with whom she had fallen passionately in love, to Epulu, a multicultural community he had founded in the 1920s. As an American woman and painter, Anne’s focus on cultural and aesthetic values and her belief in freedom and equality brought an eccentric perspective to the colonial context. Unanticipated challenges forced her to think about who she was, as she agreed to marry under unfamiliar conditions, became “one of the mothers” in the community, hosted researchers and tourists, and attempted to care for Putnam in his tragic decline.

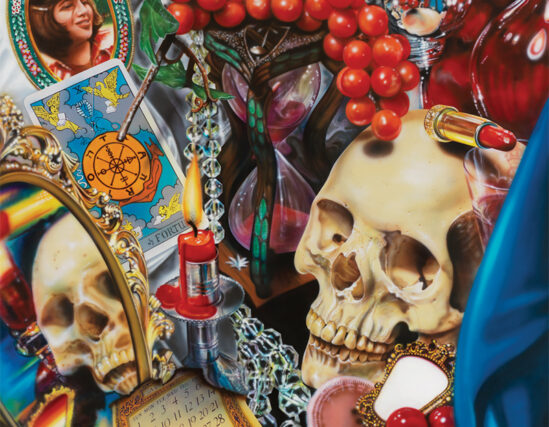

This book follows Anne’s story, based on letters, journals, and documents that reveal her experience of living between several cultures. That her art sustained her throughout as a discipline (sketching, drawing, painting) reveals to what extent, despite great challenges and heartache at certain moments, she was able to express joy in creativity; the beauty of her art testifies to its transformative power. In her later work, she continued to explore how cultural transition and memory nourished her art.

The following excerpt is from the book’s first chapter that chronicles Anne Eisner’s early life and studies at the Art Students League of New York.

Anne Eisner grew up surrounded by a strong sense of culture through social and political change for women during the early part of the twentieth century. Her older sister, Dorothy, won children’s drawing prizes and decided to be an artist for life; their dignified mother, Florine (whom everyone called Fluff), marched in the suffragette parade down Fifth Avenue in 1917, when Anne was six. The fight for voting rights marked a radical transition in women’s role in American society. Anne came of age with the stock-market crash of 1929, followed by the Great Depression and the struggle among artists and intellectuals in New York City to combat fascism and find a better world. She immersed herself in the study of art and found her way through periods of transition—social, political, and artistic—in turbulent times. If the context of one’s childhood tells a lot about the values one adheres to or resists, it does not determine the choices any of us make.

Anne Eisner was born on April 13, 1911, to William J. Eisner (1881–1975) and Florine “Fluff” Eisner (1884–1974). They were a second-generation Jewish family from Bohemia, long steeped in European culture. Anne’s maternal grandfather, Moritz Eisner (1852–1938), cut an elegant figure as the patriarch of the Eisner family. He had grown up in a quite well-to-do, bourgeois family, until his father, Joseph, a toll keeper, lost almost everything when the Austro-Prussian War began in 1866. His older brother Leopold went into the army, while Moritz was apprenticed to an apothecary in Vienna. Blessed with an excellent memory, as he writes in his brief, unpublished autobiography, Moritz studied physics and chemistry at the University of Vienna, but he spent as much time as possible backstage at the city’s Berg Theater; he loved everything to do with theater. At seventeen, Moritz decided to “try [his] fortune in the New World” and set out after two uncles, Meyer and Heinrich (Henry), who had settled in New York around the time of the 1848 revolution in Austria. Moritz, steeped in the theatrical culture of Vienna, moved to Philadelphia, where he organized a dramatic club, many of whose members were of German descent. There he met Anna Zeitz (1852–1922), a Christian, who played the piano for one of the productions. They fell deeply in love. But Moritz, who was flamboyant and generous, with a deep sense of family, had to delay marriage because he sent all his savings to a widowed sister who wished to come to the States. Once Moritz was able to make a living as a pharmacist, he and Anna married and had nine children, one of whom was Anne’s mother, Fluff.

Once established, Moritz helped his older brother Leopold (1850–1892) emigrate from Austria. Leopold went on to settle in San Antonio, Texas. Leopold’s son, Will Eisner, who would be Anne’s father, spent his childhood there, until he was orphaned at age eleven when his mother died and Leopold committed suicide over a gambling debt. Moritz adopted his young nephew Will and brought him to live with his family. Will left school to go to work when he was thirteen. Later, after Moritz founded the Newark Paraffin and Parchment Paper Company in 1903, Will became president and, with his younger cousin Stanley Eisner, made it into a successful business; they were some of the first manufacturers of waxed paper in the United States. Lore had it that Will and his cousin Fluff had fallen in love during adolescence, although they did not marry until 1905, when he was twenty-four and she was nineteen. They became a legendary couple whose marriage lasted sixty-nine years. A redhead with a Texas-tinted New Jersey accent and a hot temper, Will was a toughie; he had to be. He learned how to take care of himself and then how to take care of everyone around him. He went on to become chairman of the Waxed Paper Industry on the War Service Board during World War I, president of the Waxed Paper Association, and director of the American Pulp and Paper Association from 1918 to 1919.

As second-generation Jews, Will and Fluff were faced with the question of how much they could or would want to assimilate into an increasingly exclusionist American society. With a sense of cultural rather than religious heritage from Europe, they became involved with the Society for Ethical Culture, which had been founded by Felix Adler in 1876. Adler’s philosophy grounded the relationship between people and society in experience and living rather than belief; it focused on the individual and ethical principles within democracy that could address inequities between the privileged and the poor. “Ethical Culture,” as Adler called it, offered a third way, between Christianity and Judaism, in which Jewish heritage was remembered without religious ritual. His philosophy, going back to Immanuel Kant and the Enlightenment, continued the move toward secularization of Charles Darwin, Karl Marx, and Sigmund Freud—Adler’s contemporary—to find the definition of a moral life without theology. The premise was that ethics could be both central to life and separate from any metaphysical system. What was most radical about the Ethical Culture movement was its positive emphasis on religious diversity and the coexistence of theists, deists, agnostics, and secularists, all in the same fellowship. It was a profoundly eclectic and tolerant view of life, and the curriculum of the Ethical Culture School, founded by Adler, was based on the equality of races, freedom, and social justice. Will and Fluff inscribed a copy of Adler’s book, An Ethical Philosophy of Life, published in 1918: “this is what we believe and have always tried to live by.”

For the first ten years of her life, Anne grew up in Woodmere on Long Island. The family then moved to New York City, though she left the city to spend summers in remote areas of New England at camps with such promising names as Kearsage and Walden. Anne, the younger of the two children, was tempestuous and emotional, with a bouncy and often self-deprecating sense of humor. Like her father, she was feisty. Father and daughter got along by competing with each other combatively. Anne was more adventurous and vulnerable than Dorothy, who accommodated herself to the needs of others and avoided confrontations with her father whenever possible; she resembled her mother in this respect. Their cousin Bob Roland reflected that “Dorothy was about sixty percent conventional, and Anne was zero! Both were extremely artistic and imaginative.” As a ballet dancer and teacher of dance (and, later, a photographer), Bob Roland identified more with Anne. He remembered how impulsive and rambunctious she could be, getting herself into a jam when they were young by trying to get a dent out of a ping-pong ball: “She held the ball over a lighted match, and of course, the ball exploded.”

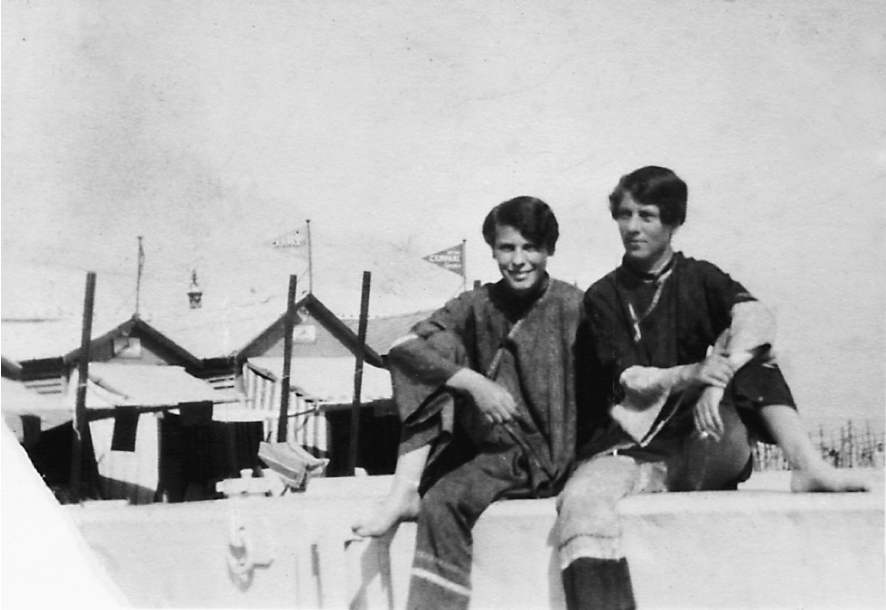

The generational change during the first part of the twentieth century, from Fluff’s “Victorian” youth to Anne and Dorothy’s feminist-minded milieu, was striking. Anne was six and Dorothy eleven when they went with their mother to the suffragette parade for the vote in 1917. Later, as young women in the 1920s, Anne and Dorothy presented themselves as wild spirits rebelling against the Victorian rules of decorum for women. They bobbed their hair in the unisex hairstyle that, it was said, had begun early in the century in Greenwich Village among escaped intellectual revolutionary Russian women, who disguised themselves as men to avoid police surveillance. By 1920, the bob was wildly popular among women, exhibiting a rebellious sense of independence and gender equality. The Eisner sisters also took on the flat-chested androgynous look in their clothing. Wearing pants and dressing as flappers (especially Dorothy), both went on to express a sense of freedom by smoking, drinking, and having affairs with men.

To the Eisner parents, the behavior of their daughters felt dangerously out of control, and they attempted to keep the girls as close to home as possible. Will was known to show up at school dances, ordering Dorothy home if he caught her with a cigarette. He had moved away from the fragility of being an orphan and from the immigrant life of his father and uncle. Will and Fluff had achieved welcome personal, social, and financial security as the world reeled through World War I in Europe. Anne and Dorothy could not identify with their parents’ need for stability. They wanted to move out and discover lives of their own.

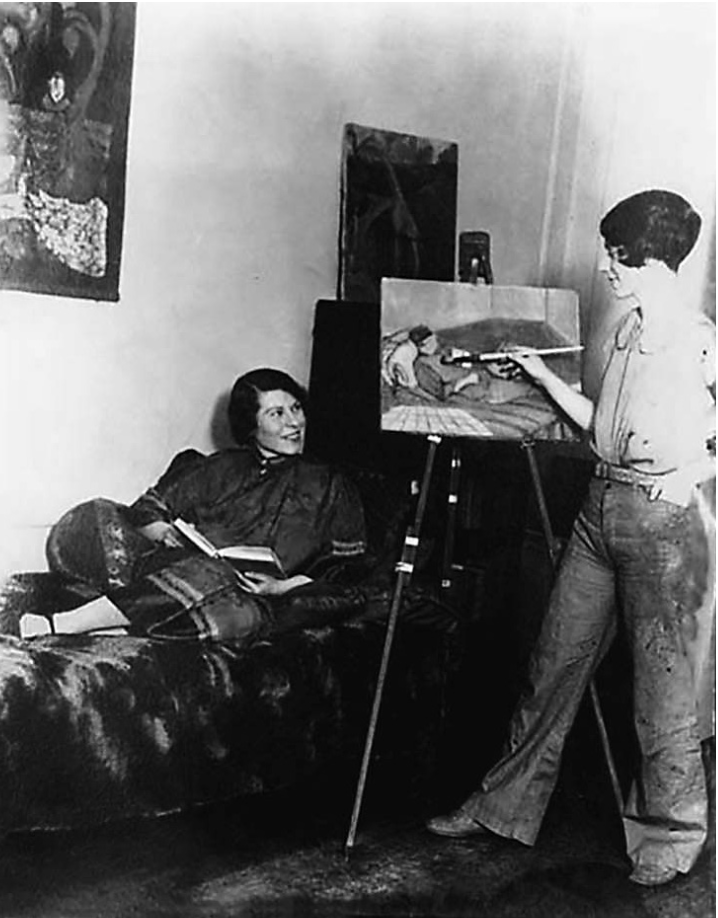

Anne grew up with a sense of art all around her as Dorothy developed her artistic talent and passion, and as she grew older, Anne would often serve as a model for Dorothy. In 1927, the New York American ran an article titled “Painter-Model Combination of Sisters Scores” about the talented young Dorothy and her model, Anne.

As close as the sisters were, and as inspired as Anne was by Dorothy and Dorothy’s close friend, Tess Slesinger, they came into young adulthood at different moments. In the mid- to late 1920s, when Anne was in her early teens, Dorothy and Tess, in their twenties, felt a passionate sense of the importance of their creative work: Tess wanted to be a writer, Dorothy a painter. They felt themselves to be modern women, although they put a distance between themselves and the splits in feminist activism that emerged after the vote was granted in 1920. They combined a flapper style (condemned as frivolous and apolitical by older feminists of all stripes)1 with a passionate sense of work. Upon receiving a rejection for something she wrote, Tess exclaimed, “You know, its [sic] absolutely incredible to me that anything we could do and send out into the world, could be ignored. But its [sic] happened to me, and I’m stunned from the shock.” Tess got it right: she wasn’t to be ignored, later writing the biting satire, The Unpossessed, about the political world around her. Anne felt herself to be in the shadow of these exuberant women exercising their freedom. It didn’t help when Dorothy and Tess shut her out—literally when they wanted to talk or a beau would visit and figuratively as the younger sibling.

When Anne turned sixteen, she worried that “there is not a single thing I can do well.” “I always have the feeling that I’m not wanted or that I’m quite unnecessary. . . . I wonder whether the majority of people feel that way or not. Not that it matters to me whether they do or not.” She blamed herself: “I have developed the greatest dislike for myself, and to think that I once had confidence in myself. It is really terrible. I get so bitter I could weep.” She understood that these feelings came from standards imposed on young women in a society bound by strictures to which she couldn’t adhere and sensed that her difference from others was fundamentally something positive, but she still seethed with anger at the inability she perceived in herself to stand strong: “To think that I should develop an inferiority complex when I know that I’m so God damn much better than most of the people.” Anne resisted giving in to silence, but she paid the price by becoming a loner.

Beyond teenage dissatisfaction, there was a more profound longing: a need to do something, to accomplish and be accomplished. “What have I done in all of these years?” she asked herself. At the age of eighteen, Anne made the decision that she could change what was around her: “I’ve decided to change in a very big way this winter. . . . I’ve decided not to sit back and wait for it but to go out after things. It’s going to be hard as hell, but I’ve found out that if you take a back seat, you have a backseat time, so—.” Anne began attending art school on Saturdays, the beginning of a quest that would last a lifetime. She noted jauntily: “Last Saturday morning our

young heroine started art school.” But no sooner had she noted the beginning of her heroine’s pursuit than she put it down: “And man was she dumb.” As further punishment for her lack of success, or rather perhaps for wanting it so much, she cautioned her imaginary reader: “So far our young heroine hasn’t met her young and gallant hero.”

Between 1927 and 1930, Anne traveled with Dorothy to France on three separate trips, where they flirted with young men and looked at European paintings. Although both absorbed lessons from the works of Paul Cézanne and Henri Matisse, neither was tempted by life as an expatriate in Paris.

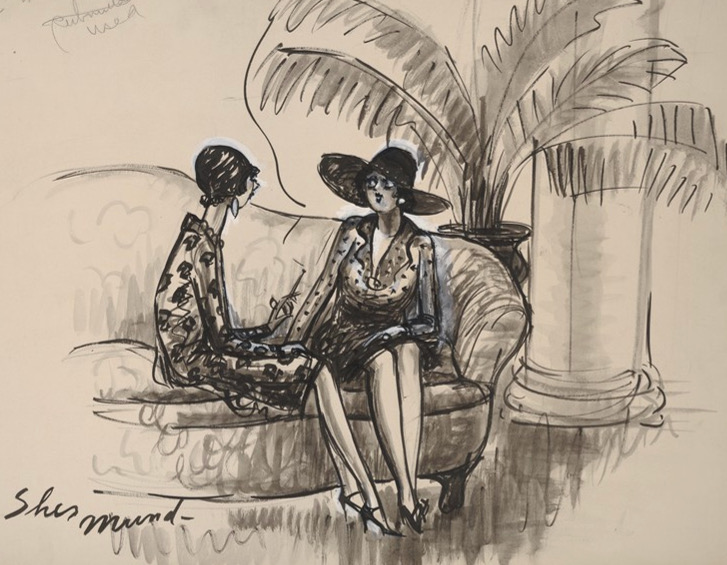

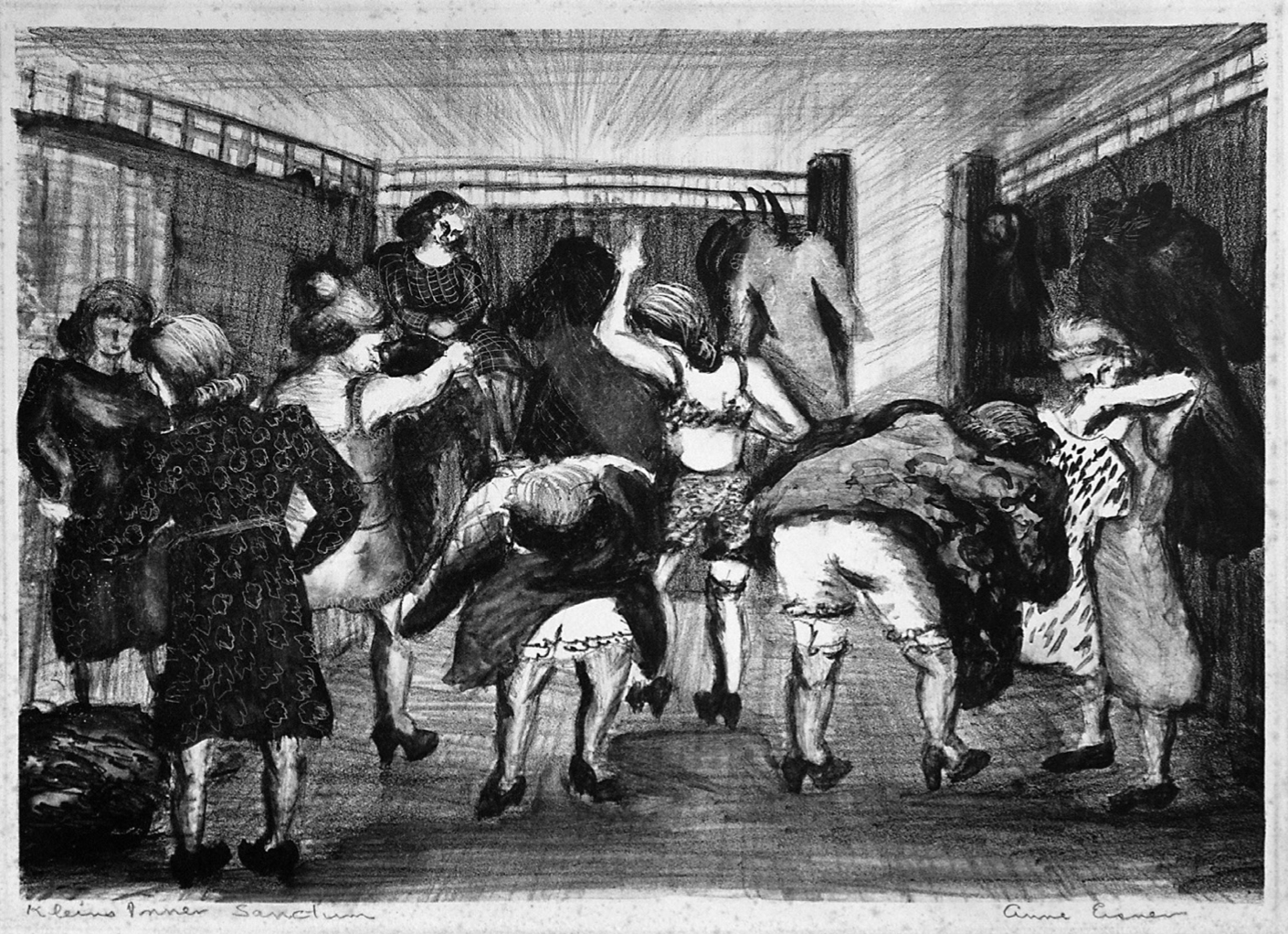

Anne trained as an artist in the tradition of Realist Revival, within the broader American Scene movement of the 1930s. She studied with George Grosz and lithographer George Picken at the Art Students League, and attended classes at the New York School of Fine and Applied Art, later renamed the Parsons School of Design. Grosz was a painter, draftsman, and illustrator from Germany, who was primarily an Expressionist. He had created William Hogarth-like satirical caricatures of urban scenes depicting moral depravity in post–World War I Germany. Grosz pessimistically characterized the Germany of the 1920s through a sense of class disparity. With the rise of the Nazis, he looked to the United States, where he came as a visiting professor to the Art Students League in 1932 and stayed until the late 1950s. In the United States, his work turned apolitical and focused on gentler caricatures of city scenes and landscapes. Under Grosz’s influence, Anne explored lifestyles in everyday activities, working, as other artists on the East Coast in the 1920s and 1930s did, with scenes of the middle and lower class in a kind of American “genre” art. She evoked slices of life as quasi cartoons in both oil and watercolor: four street scenes, women in fitting rooms, and almost anything she might see in the city.

On 14th Street, women experimented with combinations the fashion industry had not dictated. In the dominant style, everything from shoes to suit, gloves, and hat had to match. Anne shopped there in the 1930s, not only for things to wear but also for subjects to draw, such as women trying on clothes at Klein’s. Anne’s early watercolors, like the New Yorker cartoons of imperfect women sympathetically drawn by Helen Hokinson, evoked a sense of women and their foibles in the life of the city. Kenneth Hays Miller, a teacher at the Art Students League, had focused on shoppers, documenting downtown life in New York with old masters as his models (some called him “the Titian of 14th Street”) and Ben Shahn (1898–1969) photographed 14th Street and Klein’s in the 1930s. Anne went in a different direction. Gestures and moods were documented in schematized spaces, though often with irony, as a kind of social commentary with Honoré Daumier, Honoré de Balzac, and Émile Zola providing the precedent.

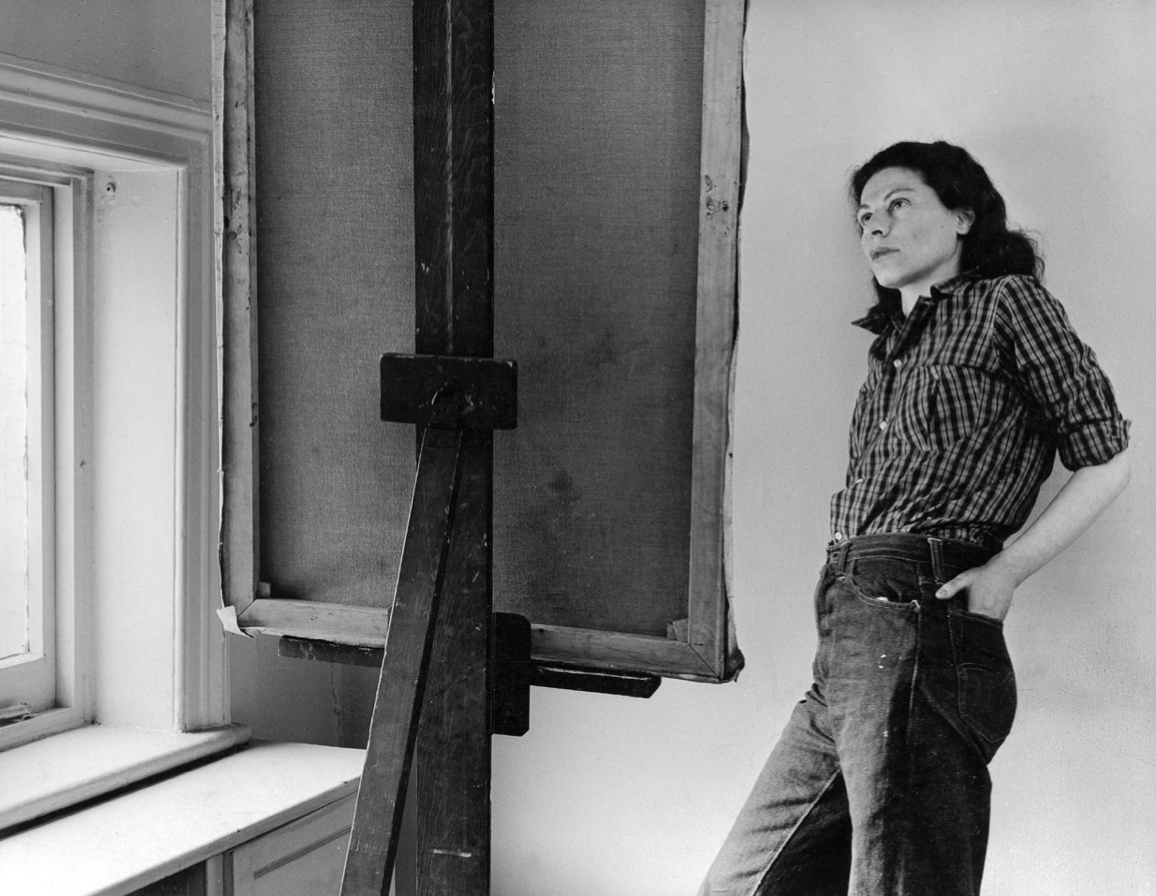

Harnessing herself into a strict discipline of work, Anne focused on practical as well as studio art. She studied costume design and illustration at the New York School of Fine and Applied Art, and at the Gloucester School of the Little Theater she worked on applied art and production. At the age of twenty, she left her family’s home on Central Park West to live in a studio apartment in Greenwich Village; it was an important step in separating from her hovering parents. Anne began to exhibit wherever she could and became a regular at the annual open-air festival in Washington Square where anyone could set out their work.

During the 1930s, Anne’s work alternated between city scenes crafted in the winter and country landscapes captured during stays on Monhegan Island in Maine, Cape Cod, Linville Falls in North Carolina, and later Martha’s Vineyard for several years. In these communities, Anne connected with a network of artists and friends. Among them was Sarah Freedman McPherson (1894–1978), whom Anne met on Monhegan in 1931 and later in 1939, a fine painter so unassuming as a person that it was a surprise for her friends to learn that Man Ray had photographed her in the 1920s in Paris and that Marcel Duchamp had given her a sketch of a “Nude Descending a Staircase,” which she had lost. Anne and Sarah exhibited side by side in a number of New York Society of Women Artists exhibitions. The McPhersons spent winters in their apartment on West 4th Street and summers on Monhegan Island, where Sarah stayed from 1928 on. Sarah had known great poverty, and her early friends in Greenwich Village in New York included John Reed, Rockwell Kent, and Eugene O’Neill (who apparently called her “the Kid”). Dorothy Eisner reflected on how hard life was for Sarah, how much she was admired by painters, and how her work should have been “a sensation.” Dorothy was quoted as saying, “It’s amazing the people who make it and the people who don’t. You can’t figure it out.” Sarah was a woman who yielded ambition to her husband, John (“Mac”) McPherson, a painter and architect, with whom Anne also studied. Among the artists on Monhegan was Anne’s teacher Emil Holzhauer (1887–1986), a German émigré who came to the United States during the early part of the twentieth century and studied in New York with urban realist Robert Henri, a leader of the Ashcan School. Holzhauer became Anne’s mentor in watercolor, one of her strengths. Anne’s early landscape work from her time on Monhegan reflected the kind of painting encouraged by the American Scene.

The American Scene movement responded to a need to document life in America realistically, even before the crash of 1929 and the government work projects for artists begun in the early 1930s. It projected a sense of the strength of American art relative to the long history of European art, with the idea of painting America as a nationalistic project. There were two groups: Regionalists and Social Realists. “Regionalists” was a title given to writers Allan Tate, John Crowe Ransom, and Robert Penn Warren in the 1920s and 1930s, with Thomas Hart Benton being perhaps the best-known artist of the movement. Ben Shahn was known among the Social Realists. Despite much debate and a diversity of styles, the two groups shared common values about art in society. American Scene artists were interested in social relevance, anecdotes, and life in local communities. The movement looked toward the future as much as the past in an optimistic way. It was democratic in the sense that artists, as members of their communities, reached out to make art recognizable in style and content; the journal Art Digest praised artists painting in this vein. They were also interested in work under the New Deal government programs of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) Federal Art Project (1935–1943) that brought a sense of community to the artists and their subjects. Author and critic Thomas Craven, a friend of George Grosz and Thomas Hart Benton, had given three reasons for the importance of the American Scene movement: the European movements had become, according to them, exhausted (they were not, as we know); modern art in Europe shunned art as a means of communication, looking instead to technique; and the American public would not be receptive to philosophical speculation and theories based on abstract notions. The positive aspects of this American Renaissance were themes consistent with the artist in his or her environment throughout the 1930s, based not on individual genius but on a more egalitarian sense of art spreading throughout the country. Benton returned from Europe paradoxically under the influence of Hippolyte Taine’s work, which constituted an important theoretical base for the American Scene, situating the artist in his or her social and intellectual milieu.

At the beginning of the 1930s, the American Scene was the “most popular movement in American art.” The Public Works of Art Project (PWAP), a temporary program, came into existence for a year, supporting thousands of artists and allowing free expression, guided by the American Scene ethos. Social Realist painter and muralist George Biddle appealed to President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933, referring to the Mexican model of mural painting, which he called “the greatest national school . . . since the Italian Renaissance,” to create a federal program of support for artists. The Metropolitan Museum of Art held a large exhibition of Mexican art in 1930, and the Museum of Modern Art put on a retrospective Diego Rivera exhibition in 1931. Boardman Robinson, with whom Dorothy Eisner had studied, and Benton both taught at the Art Students League and were interested in murals and the decoration of buildings. In 1932, Rivera painted a fresco on commission by from David Rockefeller Sr. at Rockefeller Center. Things went badly when the leftist artist put Vladimir Lenin on the right side and a picture of Rockefeller’s father drinking with prostitutes on the left. How provocative could you be? Rivera was fired, and the work was chiseled off. By the time Anne exhibited a watercolor in the Salons of America show at Rockefeller Center in 1934, there was backlash from the Society of Independent Artists’ accusations of censorship by Rockefeller Center.

Anne joined Dorothy in Linville Falls, North Carolina, during the summer of 1933, intent on painting the world that Dorothy had come to know and love there. The artist Warren Wheelock—whose connection with the Eisners came through the Woodstock Art Association—had gone to Linville Falls in the 1920s and brought other artists to the area. Dorothy had spent extensive time there with welcoming local families and wrote in a 1980 exhibition catalog: “My subjects were mountain landscapes and my friends, the mountain people, civilized as Chaucer, almost untouched by modern times.” Dorothy produced a body of work suffused with her fascination for this life in all its aspects—the people, the farming and fishing, and the exuberance of both music and dance.10 Like Dorothy, Anne was excited to be in the mountains, relishing outdoor adventures. She learned to fish and hunt possum, but she did not stay long enough to immerse herself as fully in sketching and painting.

Anne studied in Woodstock, New York, during the summer of 1935, when the Federal Art Project began. She took classes at one of the other summer schools that replaced the Art Students League, which had opened in Woodstock in 1906 but ceased to offer summer classes in 1922. The Woodstock Artists Association, founded in 1919 as the Artists’ Realty Company—of which Anne’s father, Will, became a trustee—drafted a constitution in 1920 with “the purpose of the Association to give free and equal expression to the ‘Conservative’ and ‘Radical’ elements [understood in painterly, not political, terms]”; exhibitions began in 1921. WPA support for artists and art projects in Woodstock was second only to that for New York City, enrolling some fifty artists in the PWAP. Alexander Brook (1898–1980), a summer and later permanent resident of Woodstock, was assistant director of the Whitney Studio Club, which became the Whitney Studio Gallery and later the Whitney Museum. Anne’s mother, Fluff, began studying art with Brook in 1933; Will started about a decade later with Sidney Laufman (1891–1985), a painter trained at the Cleveland School of Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Art Students League with Robert Henri, who also became a Woodstock resident. Fluff and Will followed their daughters’ passion for art, making it their own, and their artistic practice continued throughout the rest of their lives. They bought a farm in Woodstock in the 1950s and went on to show their paintings extensively. Many artists settled in and around the village, among them Anne and Dorothy’s friend George Ault (1891–1948), who painted in the American Precisionist style, influenced by Cubism and Futurism, although he remained quite realist. Woodstock was well established as an artists’ colony, attracting painters, sculptors, craftspeople, and photographers, long before it became associated with the Woodstock music festival in the late 1960s. During the summer she was there, Anne produced work for her debut solo exhibition of watercolors. In her first years of exhibiting, Anne regained a sense of self-confidence and, with high-spirited boldness, signed her paintings simply “Anne.” Art reviewers loved her moxie, referring again and again to the girl “called Anne” as they singled out her work for comment in group exhibitions. A reviewer also praised Anne’s watercolors shown with the Society of Independent Artists of 1934: “Particularly good may be considered the several watercolors by an artist known to her public simply as Anne.”

By 1943, her teacher in the medium, Holzhauer, commented about her development in the solo watercolor exhibition at the 8th Street Playhouse:

It is always interesting to me to watch the growth of an artist from the earliest growings to mature expression. Her first attempts showed a strong grasp of the essentials in a picture, a rather quaint slant on subject matter, and arresting color. Now these qualities have become the outstanding features in her work. I know of no other woman artist who handles watercolor with such boldness and directness.

Anne certainly exhibited with women artists and was conscious of herself as a woman, but it is worth noting that Holzhauer praises her in a category of women artists and does not contrast her work with that of male artists.

In one of her early watercolors, Cathedral Woods, painted on Monhegan Island, Anne grouped trees together to show a pattern of space. Her fascination with trees was to be lifelong, from distant and overarching views to closer, more existential engagement, abstracted in later watercolors and paintings. The forest evolved throughout her work as a metaphor for life’s complex problems. Little did she know that later on, both forest and life would thicken when she went to live at the edge of a tropical rain forest in Africa.

CHRISTIE MCDONALD is the Smith Research Professor of French Language and Literature in the Department of Romance Languages and Literatures and Research Professor of Comparative Literature at Harvard University. The Life and Art of Anne Eisner An American Artist between Cultures was published by Officina Libraria, Milan, in November 2020.