In 1906, three years before Marion Greenwood’s birth, Anthony Comstock, secretary of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, joined the police at 215 West 57th Street. In the landmark building that houses the Art Students League, they arrested the bookkeeper and confiscated copies of the July issue of the American Student of Art magazine, which contained images of nudes that were, at least in Comstock’s mind, scandalous. Champion of Victorian-era values, Comstock was out to banish “obscene, lewd, or lascivious” publications, which even included birth control materials. Copies of the American Student of Art likely landed in one of his notorious bonfires, but the students had their revenge. Comstock’s effigy soon hung from the building’s third floor, their adversary described as a “sexless clown who shunned love’s hallowed fire.”

The Art Students League League, one of the country’s most progressive art schools, began as a protest against the stuffy National Academy of Design. At age fifteen, Marion Greenwood joined their rebellious ranks. She had begun sketching at age six, producing her first painting at nine: a portrait of Cleopatra preparing her suicide. Already considered a prodigy, she abandoned Erasmus High School in Brooklyn for the League in 1924. She went on to become a celebrated muralist, easel painter, and printmaker described by the National Museum of Women in the Arts as “arguably one of America’s greatest twentieth-century women artists.” She won prizes from the Carnegie Institute, the National Association of Women Artists, and election to the National Academy of Design. Numerous national and international museums own her drawings and paintings, many of them portraits inspired by her foundational years at the League.

Between 1924 and 1929, Greenwood made her way from her home in Sheepshead Bay and later Flatbush to the League via the Brighton Beach line. But the fifty-five-minute subway ride from her sleepy Brooklyn enclaves to Midtown was a cultural as well as temporal journey. En route, Marion might have witnessed signs of social foment: workers striking for safer conditions and better pay, as well as women marching for the right to birth control and greater autonomy.

Marion’s very presence at the League revealed gender shifts from an earlier generation. In the early nineteenth century, women with creative inclinations painted landscapes or did needlework to enhance their “feminine nature,” making them more marriageable. By the late 1800s, some art academies in the US and Europe began to accept women. But opening did not ensure equal education.

In contrast, the League had accepted women from its foundation in 1875 and insisted on gender equality on the school’s governing board.

When Greenwood entered the League, students auditioned for a space in George B. Bridgman’s popular class by drawing a live model, arriving forty per day until a select few rose from the long applicant list. The same confidence that led her to walk away from high school likely steadied her hand the day she gained entry on her first try. Bridgman became Greenwood’s mentor. Though the school’s fees were modest – she initially paid $13.00 for a full-time class — he also helped her secure scholarships.

In 1925, Greenwood enrolled in a life drawing and painting class with Frank Vincent DuMond. DuMond had been a League student in the 1880s and then travelled to Paris to continue his art studies. He eventually returned to New York and began teaching an antique class at the Art Students League in 1893. Greenwood would follow that well-trod path to Paris, studying at the Académie Colarossi. She paid for the trip with money she earned from a commission for a portrait of Spencer Trask, one of the founders of Yaddo, an artists’ retreat in Saratoga Springs, where she was awarded one of the art colony’s earliest residencies in 1927.

In 1929, Greenwood’s final year at the League, she studied with John Sloan, who was part of the Ashcan School. Launched by Philadelphia painter Robert Henri, the group was more a loose affiliation than a school. The term “ashcan” was a tongue-in-cheek reference to their gritty urban subject matter. Paintings such as Sloan’s Backyards, Greenwich Village, with clotheslines strung between apartments, modeled for Greenwood how to portray city scenes, tenements, and workers in daily life. Her portrait of a tailor on the lower east side is one of the many that offer homage to Sloan.

As a socialist and one-time art editor of The Masses, Sloan likely kindled Marion’s leftist sympathies and lifelong passion for depicting the poor, immigrants, and workers. Those would find full realization during her nearly four years in Mexico in the 1930s. At the Hotel Taxqueño in Taxco, in 1933, she painted a market scene, the first mural by a woman in Mexico. The same year, Greenwood created a second-story, 86 x 14-foot mural in Morelia, Michoacán, celebrating the lives of indigenous people. Ascending the scaffold each day, she endured catcalls and slurs on her reputation, for what kind of woman would defy social norms and appear publicly in men’s overalls?

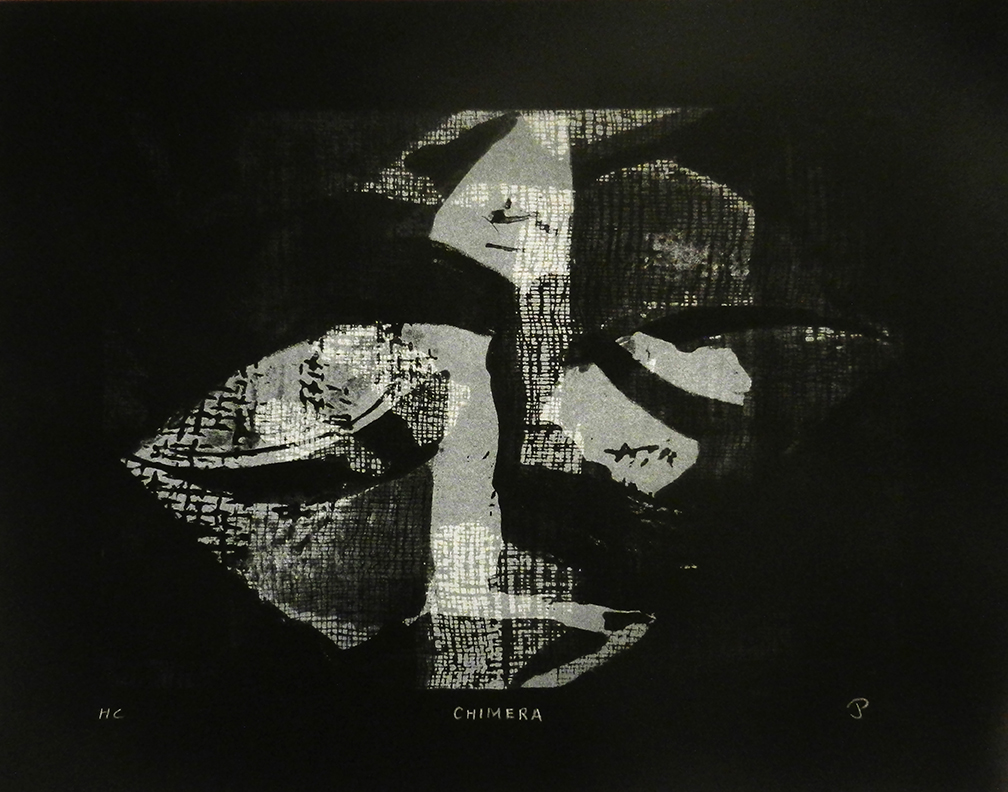

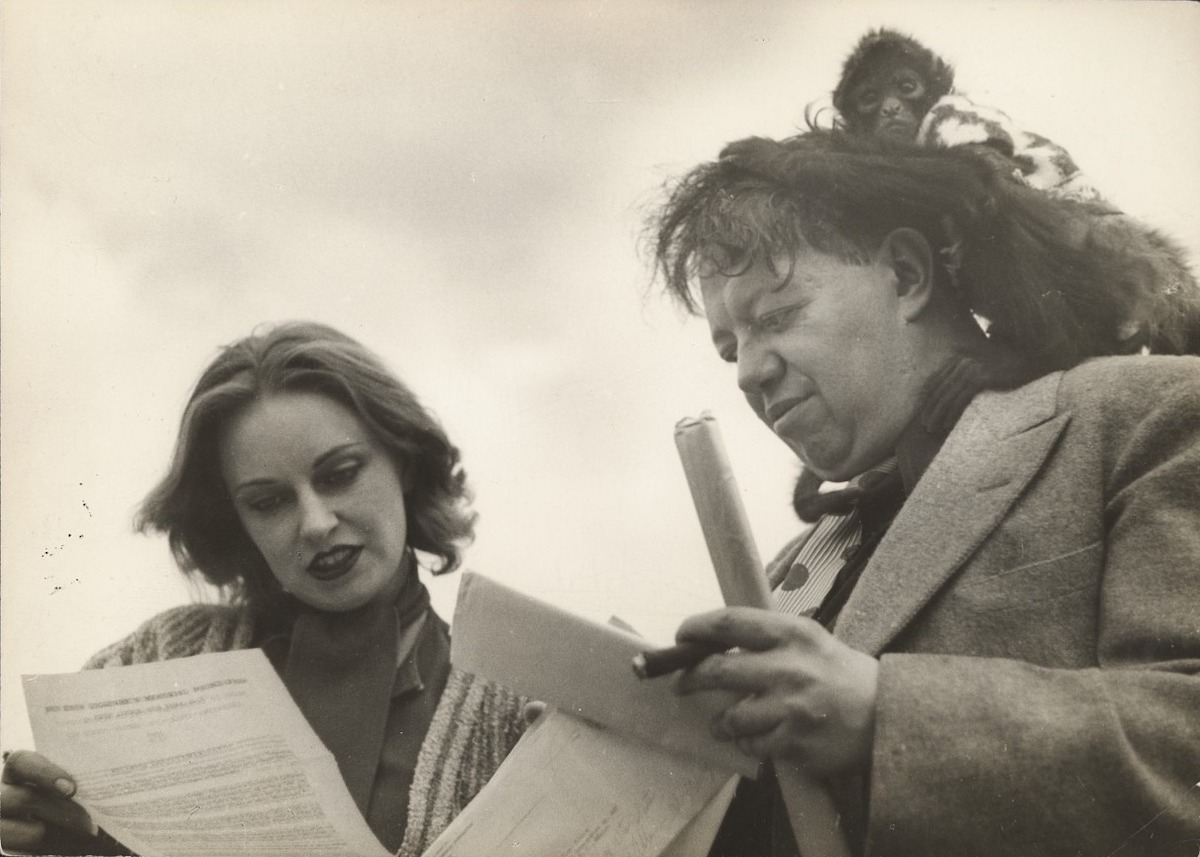

In New York and Mexico, Greenwood socialized with “los tres grandes” – Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and José Clemente Orozco. But it was pioneering American artist Pablo O’Higgins who urged her to join a group mural project in Mexico City’s Abelardo L. Rodríguez market. Her complex and visually dense mural The Industrialization of the Countryside is now featured in the Vida Americana exhibit at the Whitney Museum. Art historian James Oles describes how Greenwood “conquered the technical and compositional difficulties of fresco to create among the most powerful antifascist and proletarian works” of the era. Upon returning to the US, she pursued easel painting and printmaking, while also painting murals for the WPA’s Federal Art Project, the University of Tennessee-Knoxville, and Syracuse University.

At the League, Greenwood likely first encountered a teacher who helped shape her commitment to diverse cultures. Artist and illustrator Winold Reiss began lecturing at the League in 1915, two years after he immigrated from Germany. He provided illustrations for Alain Locke’s The New Negro and painted portraits of the major Harlem Renaissance figures. New York, like the rest of the US, remained segregated in the 1920s, but Reiss’s studio and the League were two places where whites and African Americans mixed. Painter and educator Theresa Pollak, whose student years overlapped with Marion’s, praised “the easy mingling here [in the League lunchroom] of models, students, instructors, and visitors, irrespective of race, sex, creed, or differences in life style.”

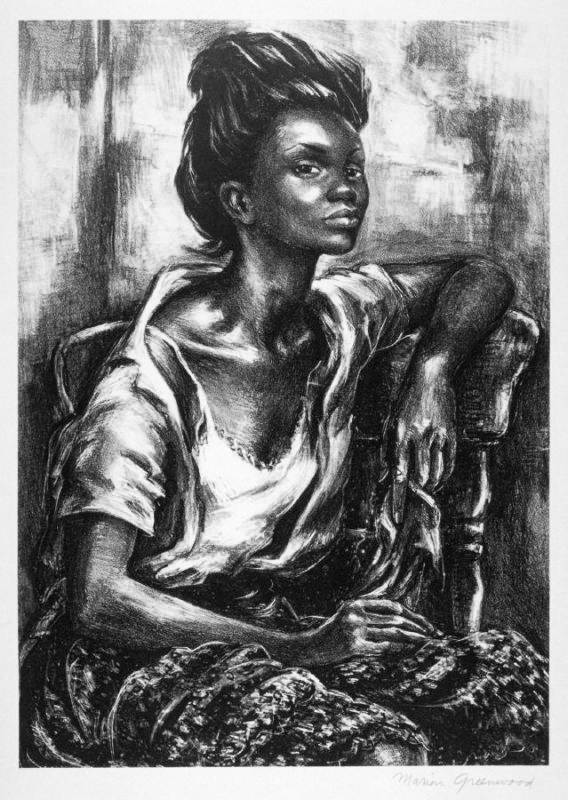

Reiss’s zeal influenced Greenwood. She painted subjects as varied as Mexican workers, African American dancers, Haitian Vodou practitioners, and Chinese farmers. Like Reiss, she tried to discover individual character beyond the then popular idea of “ethnic types.”

Did Greenwood succeed in representing diversity? In a 1948 review in American Artist, Ralph Pearson praised her award-winning portrait of the African American Mississippi Girl as revealing “the uncanny power of this artist to capture and dramatize the inner, as well as the outer, nature of her subjects.”

Others disagreed. Based on work completed during almost two years in Hong Kong, one critic argued, “Miss Greenwood draws the Chinese the way they look to Americans, but plunged no deeper… How could she? She is not native and could not tap the hidden springs.” The critique sounds surprisingly contemporary given our discussions of cultural representation. Surely Greenwood sometimes faltered, as not every work reflects the sensitivity audiences might seek or that she likely felt. That she focused on women, workers, the poor, and those outside her own world suggests she was a sensitive observer with a wider lens on contemporary life than many of her peers. In a call for indigenous self-representation rare for the time, she wrote while in Mexico, “Why should I [paint] when the Indians themselves are such swell artists. They should be given a chance to paint walls.”

Greenwood was one of the few women of her era who supported herself and helped her family through sales of her art. Financial need may partially account for her adherence to realism, which continued to sell. But more likely, despite her exposure to expressionism, surrealism, and other styles, she stubbornly refused trends. “I think of art in a long-term basis which is why I’ve never been concerned about being in fashion.” She lamented what she saw as the destruction of the human element in later twentieth-century art. After gallery visits to see new work, she would return to her studio to paint portraits. “I’m just myself again. I can’t help it!”

That self was forged at the Art Students League. From the day Greenwood left Erasmus High School until her death in 1970 from a cerebral hemorrhage at age sixty, she carried the League within: the school’s progressive politics, egalitarian ethos, rigorous training, and inspirational teachers of anatomy, life drawing, and portrait painting.

Joanne B. Mulcahy of Portland, Oregon, is currently writing a biography of Marion Greenwood. Her books include Remedios: The Healing Life of Eva Castellanoz and Writing Abroad: A Guide for Travelers (with Peter Chilson). Selected essays and articles are featured on her website: joannemulcahy.com.